(A little bit of prologue: I began researching for and writing this double book review essay about three years ago. I did not know then that I would not finally complete it and have it ready to post until February of 2025, nor did I know that the collapse of the U.S., the nation I was born and raised in, would occur in that same year. This essay provides a little bit of explanation for that collapse, but mainly tells a much bigger story about the roots of all of the national and biological collapses that are unfolding now, at this climactic moment in human and Earth history.)

(Last edited: July 5, 2025. I just added a brief summary description of each of the “Nine Planetary Boundaries” and corrected a few typos.)

“Wow! This looks like a lot of writing. Where might this ‘rabbit hole’ take me, if I decide to dive in and read it?” This double book review will discuss, explain, and provide some answers to the following questions:

- What is the biggest real threat to all life on Earth that we currently find ourselves needing to face and respond to?

- How did we arrive at our current predicament?

- Why can’t we continue with a growth-dependent, competitive economic system and simultaneously reverse the life-destructive, self-destructive course that we currently find ourselves propelled upon?

- Why can’t our available and developing technologies save our customary ways of living and simultaneously preserve Earth’s living system?

- Will we ever find a “Planet B” and is it worth sacrificing the only beautiful, generously life-giving planet that we actually still have in a futile attempt to try to find and actually travel to such a place?

- What is Mother Earth asking us to consider and to do now? (the most important question of all)

Preface: a statement of purpose and intent

Why am I writing this? Do I think that the facts, analysis and arguments that I present here will change anybody’s (or some significant number of persons’) mind, priorities or actions? Considering the widespread increase in misinformation, combined with the growing cultural tendency (in many human cultures, but especially in the U.S.) to value beliefs over facts and to even ascribe social honor to people who “stand steadfast” in whatever beliefs they hold, regardless of facts, I do not expect whatever I end up writing here to provoke much change. For many reasons, I do not expect that this piece of writing can help much to propel the necessary massive change in human behavior and status quo institutions quickly enough to avoid the severe, life-extinguishing consequences of human ecological overshoot already set into motion and already occurring increasingly all over the planet. Even so, I still feel compelled to make the effort. One reason for that is, based on the experiences of myself and many others whom I know surrounding sudden, tragic loss of the lives of dear ones, I anticipate that the increasing disastrous occurrences that the world is now facing will cause more and more people to ask these three very difficult questions: 1) Why is this happening to us? 2) What could we have done differently to prevent it? 3) What can we do now to move forward, into a better, healthier way of life? I hope that I can provide some degree of comfort or consolation to people by providing some legitimate, fact-based answers to those questions.

Once those first three questions are addressed, another question naturally arises: If people already knew about these things that are happening to our world now and their potential consequences fifty or more years ago, why didn’t they tell everybody and why didn’t governments do more about it back then, when it might have made a more significant difference? Well, many people actually did speak up, explaining the situation and proposing possibly appropriate actions or responses—including, William R. Catton, Jr., the author of the two books discussed in this book review/essay—and many people heard it and began taking some appropriate actions right then, but apparently not nearly enough.

Do I think that answering the “why” questions, even if that could help a large majority of humans come to understand the actual predicament in which we now find all life on Earth, will actually be enough to provoke the actions necessary to significantly slow down or reverse the currently accelerating trajectory of destruction? Probably not, for many reasons that I will elaborate on in the following pages. Nevertheless, I continue to communicate and try to help people around the world prepare for any possibly viable, sustainable paths forward in the face of the collapse of familiar societal structures and regional ecosystems, throughout planet Earth. I do this not because I think that I have any particular powers of persuasion or even any adept abilities with the written word. On the contrary, most of what I have written in the past on these topics seems to mostly inspire doubt, dismissal, and possibly disgust. That might be an overly negative conclusion, but I can only guess at that because very, very few people ever comment upon or engage with me in discussion of my writings at all. Maybe it is just the topic itself that is too repulsive or overwhelming for most people to engage with. Ironically, it is that very phenomenon of all that is unknown—what I do not know about the effectiveness of my attempts at communication and what I actually do not know about future possibilities for life on Earth—that also compels me to continue with my efforts, “just in case.”

Another reason that I keep hacking away at this endeavor is that I just cannot sit back and do nothing while I witness so much suffering (for all species, especially the innocent victims who have not contributed much at all to creating our dire circumstances), or when I consider the possibility that some may be spared some of the pain due to something that I might possibly be able to do or say for them. Beyond the act of writing or the use of words, another thing that I have found I can do that might be helpful is to show people how my family and I have been living and learning with the natural world for most of the last 53 years, especially in the last 20 years. We can teach ways and practices that could be useful and beneficial to humans and simultaneously beneficial to the other living beings whose ecosystems we share, both now and post-collapse. Maybe I am just writing this for some potential benefit for the future survivors.

Diving In: William R. Catton, Jr. and the circumstantial context in which he wrote, Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change (first edition published in 1980)

The environmental sociologist, William R. Catton, Jr. (1926-2015), was by no means the only person in the 1970s, researching, analyzing and writing about the actual predicament of life on Earth, but many people writing and thinking on that topic today cite Catton’s Overshoot as the first or most important book that they ever read explaining the real causes and actual severity of our current global ecological crisis. I will cite some of the other writers and thinkers of that era who worked on the same subject in my links, but for now I will just say that the list includes the co-authors (Donella H. Meadows, Dennis l. Meadows, Jorgen Randers, William W. Behrens III) of the groundbreaking 1972 report, The Limits to Growth, and the several works of that decade by Paul R. and Anne H. Ehrlich (post 1968’s controversial, The Population Bomb). As monumental as those works were, many leading ecological writers of the last thirty or so years cite Overshoot as the pivotal or most influential book to help clarify their understanding of our complex, multi-faceted ecological and societal crises. Even so, the vast majority of humans, even those of Catton’s own country (the U.S.), and probably most of those who call themselves “environmentalists,” have never heard of William Catton, his book, Overshoot, or even the concept of overshoot itself! Why is that so? We will discuss some reasons for that in what follows below.

Overshoot was published in 1980 and Bottleneck was published in 2009. I will begin with Overshoot and follow that with a brief discussion of Bottleneck that will include some comparative referrals back to the earlier book. I read the books in that order and found such comparisons to be both fascinating and informative. William Catton was a man of my father’s generation, born in 1926 (one year before my father). Catton was 83 when he self-published Bottleneck and had been retired from academia for 20 years at that time. There were several things that I noticed while reading Bottleneck which probably would never have occurred to me had I not had some experiences similar to Catton’s, within academia, after retirement, in the liberating experience of self-publishing, and in the experience of aging. I will describe and elaborate on some of those experiences and thoughts within that section of this double book review, along with a little more biographical information about William Catton.

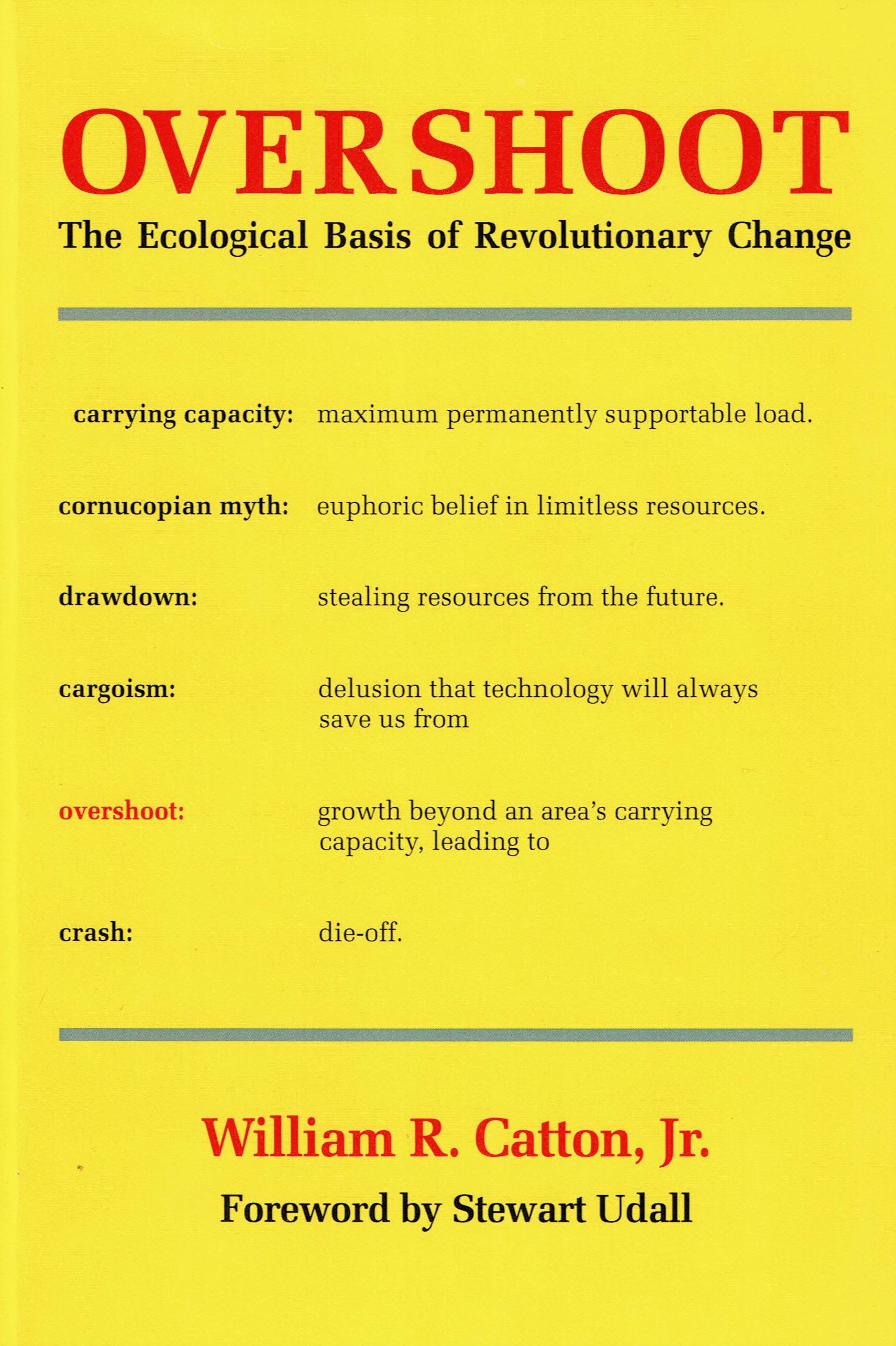

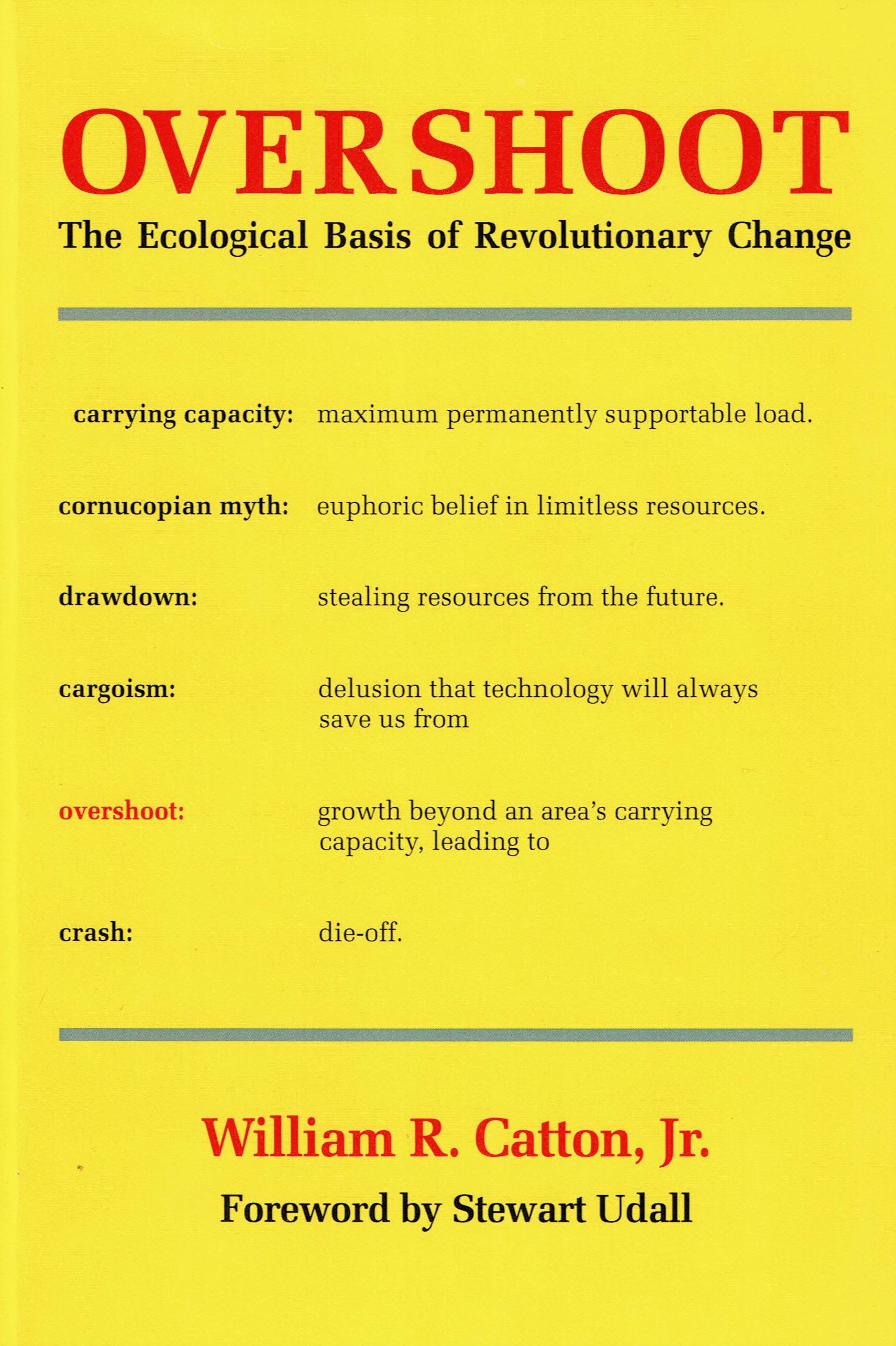

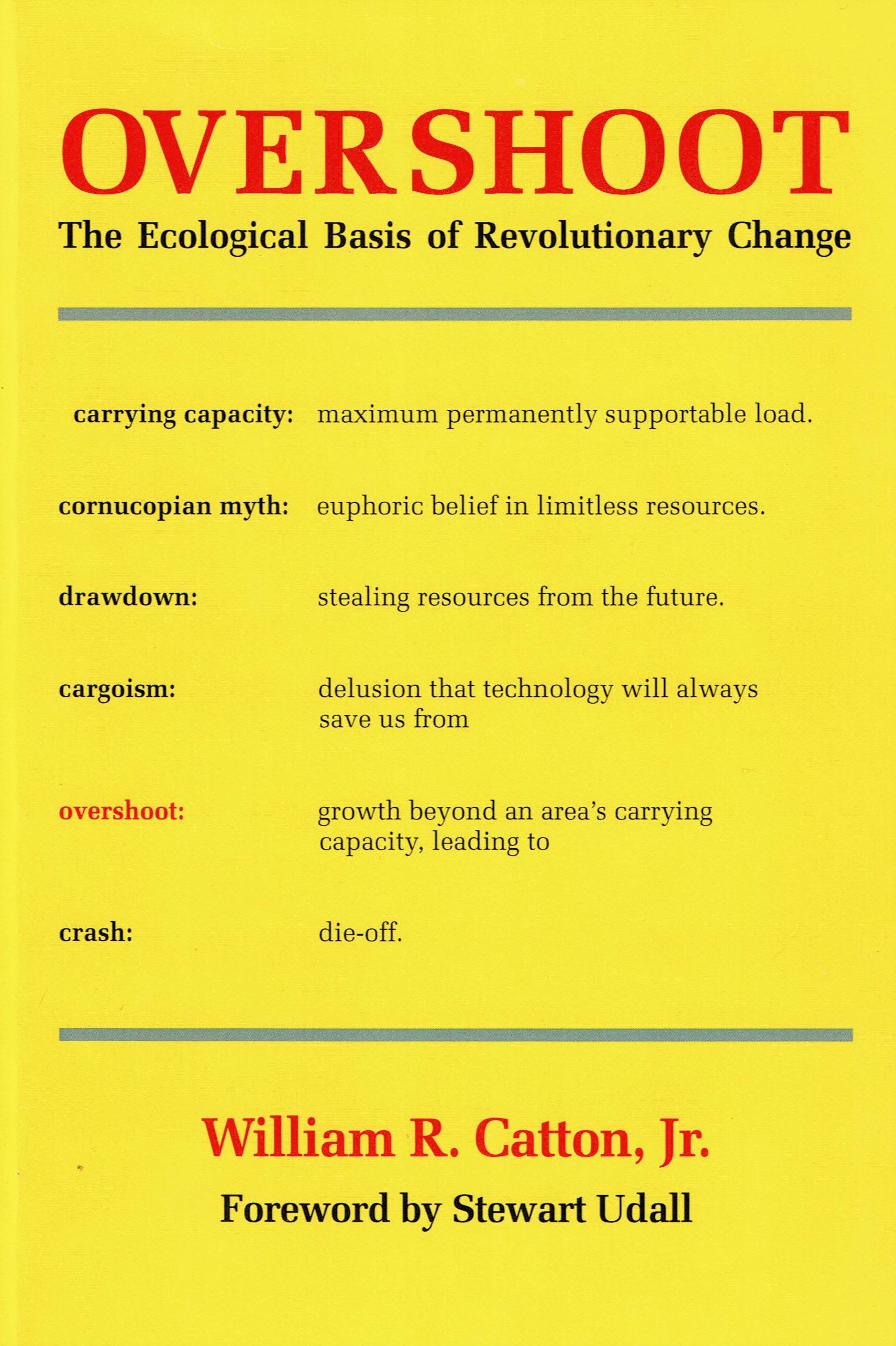

As can be seen in the cover image of the book, Overshoot, it is the only book I know of which begins its text on the cover instead of on its pages within. There, on the cover, we find six extremely important terms, along with their definitions, which are all elaborated upon further in the pages within, and are essential to understanding the author’s main points. While reading this book, long before I had finished it, it became very clear to me that unless a person understands the relevance of those six terms to our current global ecological predicament, they have completely missed the point and do not understand our actual predicament at all! More on that as I go through my analysis of the book and its message.

We also see on the cover the book’s subtitle, “The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change.” Sometime after I finished reading the book, while I was contemplating further why Catton had not seen any need to spend much time at all directly critiquing capitalism within its pages (more on this later), I received a possible revelation about that subtitle. I had wondered why Catton had not used the word “for” instead of “of” before the phrase “Revolutionary Change.” After all, he was writing the book during the 1970s, when there was still a good number of people going around proclaiming the need for and justifications for revolutionary change, or for revolution itself. Having been personally acquainted with that movement at that time, I just naturally wondered why Catton had not used that word. Eventually, it became clear to me that Catton was not talking about any type of human-devised revolution. Although humans have contributed greatly to creating the conditions for the “revolutionary” changes which Catton perceived to be coming upon our whole world, he also saw that this revolution was not intended by or consciously devised by humans. The revolutionary changes which Catton foresaw and wrote about in Overshoot are the natural consequences of human excess and misdirection—the violation of natural laws and the exceeding of the carrying capacities of our local and global ecosystems. In a sense, this current global crisis (overshoot and crash) could be described as Earth herself “revolting” against the ability of humans to carry on with their life-destructive ways any further. But it could be more accurate to describe it as Catton did: that finite Earth’s long-ago-established interactive laws, limits and the natural consequences of breaking those laws are the ecological basis of the revolutionary changes to Earth’s life systems that we are now observing with accelerating frequency, intensity and damage, not only to living species and ecosystems, but also to the infrastructures of human societies. The overheating of Earth’s atmosphere, the increasingly intense weather events, the droughts, fires, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, rising sea levels, ocean acidification, dramatic reductions in biodiversity, and losses of habitat, are all revolutionary changes that have an ecological basis that existed prior to human or anthropogenic violations of natural law. The consequences for those violations were already built into Earth’s system. The early human societies, and many Indigenous peoples to this day, had/have many stories that refer to the “Original Instructions,” or natural laws, including our symbiotic, mutually beneficial relationships with all Earth Life, and warnings about the consequences of violating those laws and breaking those relational connections (more on this later). William Catton perceived that this natural revolution will, ultimately, supersede or overrule any human attempts at either revolution or reforms, or at preserving the societal status quo, and will ultimately determine the limits, possibilities, successes or futility for all human plans and ambitions.

So much for the book cover, the title, and the table of contents. Now we can go on to discuss the rest of the book. 🙂 Don’t worry. Of course this book review will not attempt to cover every page or even every chapter of the book. I only intend to cover some parts of the book which expound upon the six terms on the book’s cover in ways that will address the six vital questions that I raised at the beginning of this book review essay. Along the way, I will bring in material from the works of more recent writers and researchers which have confirmed and expanded upon the findings and ideas that William Catton brought forward so long ago. Citations for those works can be found in the hyperlinks, to help facilitate your own research and further understanding. I think that I should mention here that Overshoot has an index but, unfortunately, Bottleneck does not, probably because it was self-published (I learned from my own self-publishing experience that indexing is a very difficult process and expensive to hire somebody else to do it).

William Catton did not invent the concept of overshoot, nor was he the first to “discover” it. If he were here today, I think that he would agree with me that it is much more urgent for people to understand Earth overshoot than to become familiar with Catton’s biography. Therefore, I will dive right into the topic of overshoot now, and interweave a little more of the relevant biographical information on Catton wherever it seems appropriate within the context of this essay. Probably, the most relevant biographical material would revolve around how he came to see that sociologists should pay more attention to a society’s relationship to the planet upon which we live and depend on for our biological needs, and our interactions with the particular ecosystems where we are located.

Carrying Capacity and Overshoot

Humans can easily understand that a drinking glass has a limit to how much liquid can be poured into it, or the limited number of dinner guests that can be adequately served by the meal that the chef already prepared. But it seems to require exceptional, sometimes strenuous, effort for most humans in this modern, alienated-from-nature world to grasp that a living system as large as Earth can also have maximum limits or capacities. In the first chapter of the book, Catton provides us with a more detailed definition of carrying capacity than the brief one on the book’s cover:

An environment’s carrying capacity for a given kind of creature (living a given way of life) is the maximum persistently feasible load—just short of the load that would damage that environment’s ability to support life of that kind. Carrying capacity can be expressed quantitatively as the number of us, living in a given manner, which a given environment can support indefinitely.

What is not clearly stated in that definition, but is mentioned by Catton elsewhere, is that local ecosystems on Earth (what he calls “environments” here) never contain only one species of life. But, for the purpose of illustration, it is sometimes easier to explain carrying capacity using one species, with certain specific types of behaviors, and then add in other species and behaviors to illustrate the more complex aspects of carrying capacities within actual, bio-diverse ecosystems. Another thing that complicates determining the carrying capacity of a particular place or ecosystem for accommodating human residents is the widely varying behaviors of humans when they are present in an ecosystem. Unlike more compliant-with-nature or behaviorally predictable species, such as deer, for example, whom we can confidently predict will confine their behavior to activities such as grazing, browsing, drinking water, sleeping, protecting their young, etc., and never destroy forests or build parking lots, humans are very different. Some humans might behave very recklessly, selfishly, and destructively in their approach to life and relationships with other life forms in their ecosystem, while other humans can behave nearly as harmlessly as a deer, with a broad spectrum of attitudes and behaviors in between those extremes. Consequently, when attempting to assess or quantify the carrying capacity for humans in a given place, it is essentially important to clarify what types of humans, with which types of behaviors, would be living in that place.

There is one type of behavior that both humans and non-humans can and do sometimes engage in which can very significantly impact the carrying capacity of their homeland: excessive reproduction, to the point of overpopulation. Even if all of the other behaviors of the inhabitants of an ecosystem are compatible with the living system of a particular place, overpopulation by itself can lead to overshoot. When a species has overshot the carrying capacity of their homeland for their particular species, they will eventually run out of food and experience “die-off” or “crash” (extreme population reduction, or local extinction). Some members of the overpopulating species might migrate to another location before crash can occur. Both of those paths (die-off or migration) are ways that Nature brings an overload of a particular species back to a level that is sustainable for local carrying capacity. Most of the disastrous human-caused errors that significantly affected the history of our species, are rooted in humans living in ways that try to mitigate overshoot and avoid death or migration using practices and devices that oppose natural laws and systems. Catton’s books and my comments in this essay will show in some detail examples of how that has occurred. It is also important to realize that the impacts of overshoot caused by one species are never limited to that one species, alone, since all life in any place is interconnected and interdependent to some degree.

What Catton meant in the above definition of carrying capacity, when speaking about an “environment’s ability to support” certain forms of life and their associated behaviors “indefinitely,” is referred to by most people who speak on the topic these days as an ecosystem’s ability to “regenerate” itself, perpetually. That is what ecosystems do naturally, unless one or more of the species residing within the system reaches overshoot, through over-population, over-consumption, excessive production of waste, or some combination of all of those. That brings us to another, or just re-worded, definition of overshoot, found in the glossary at the end of the book:

OVERSHOOT: (v.) to increase in numbers so much that the habitat’s carrying capacity is exceeded by the ecological load, which must in time decrease accordingly; (n.) the condition of having exceeded for the time being the permanent carrying capacity of the habitat.

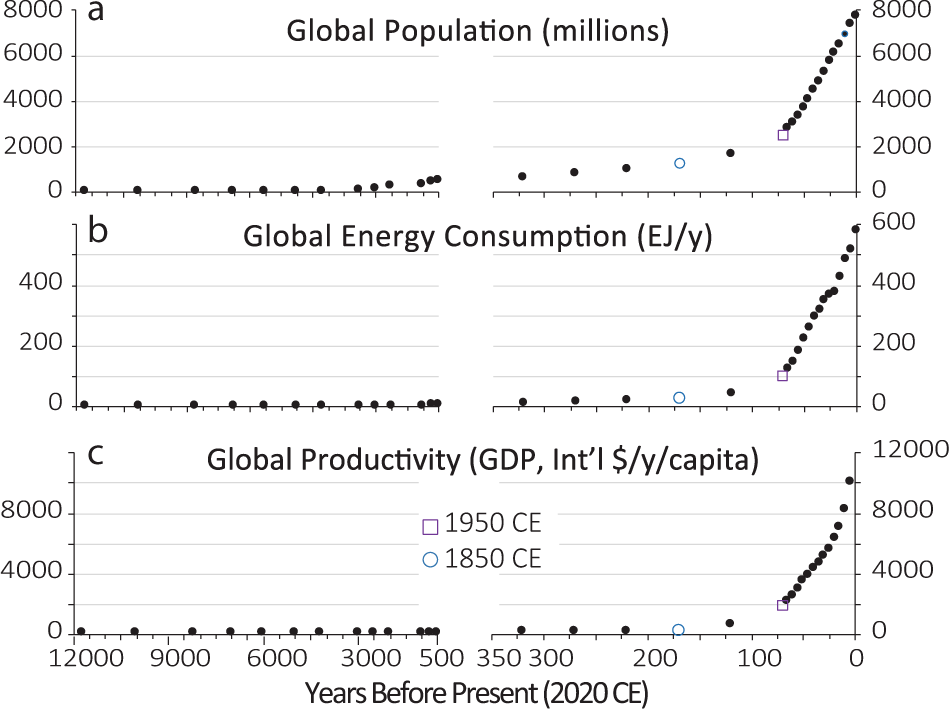

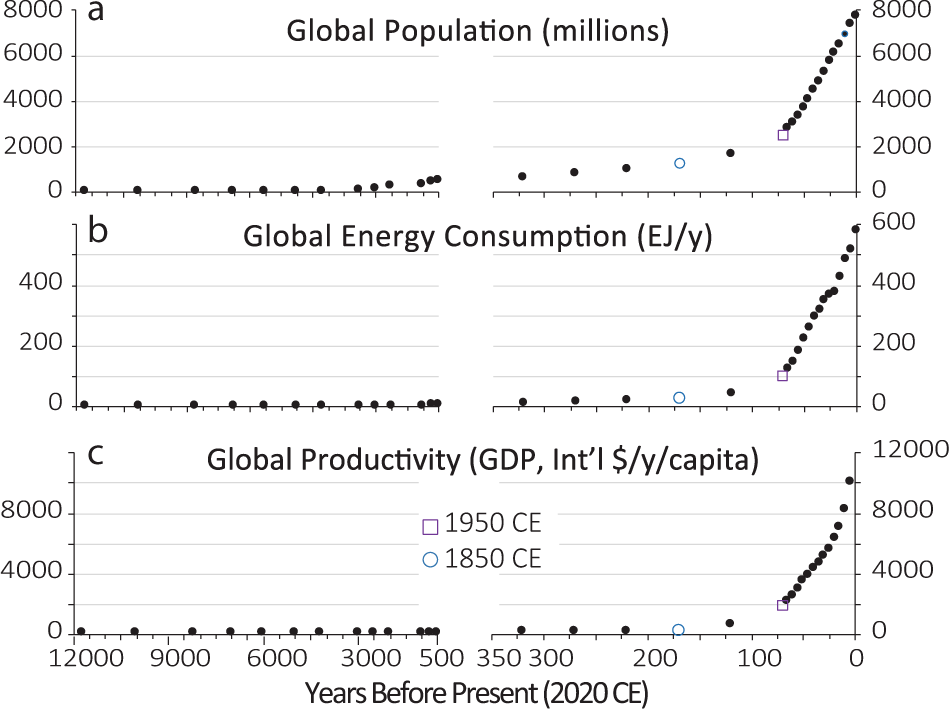

At the time that Catton was writing Overshoot, the “increase in numbers,” or human over-population, was at the forefront of the minds of most of the relatively few researchers who were giving overshoot any serious consideration at all. The global human population reached 4 billion in 1974, which was double what it was in 1925 and quadruple the world population in 1805. Although the population doubled again in 2023, hitting 8 billion, the annual global rate of growth (currently, 0.8%) and the global fertility rate (GFR) have both declined significantly over the last several decades and many scientists project that GFR will fall below replacement level (2.1 births per woman—we are currently at 2.3, were at 3.0 in 1992 and 5.3 in 1963) within the next ten to twenty years. As global birth rates have fallen and death rates risen, some demographers estimate that human global population will peak sometime between 2040 and 2080. During the same time that those population dynamics have come into play, human material extraction, consumption, and waste production have continued to rise at very high rates. For example, during the last five decades, in which the population doubled from 4 billion to 8 billion, the rate of energy usage tripled. I will expound on those human industrial and consumptive behavior issues more later, but for now what is important to realize is that overshoot, both locally and globally, can, in some cases, be more a result of human behaviors (what type of humans live in a given location) than just human numbers.

Some scientific methods for looking at and precisely measuring carrying capacity and overshoot have been developed over the last thirty years by the Global Footprint Network, based on work done in the early 1990s by William Rees and Mathis Wackernagel. I do not know those two men personally, but I have heard that their work was inspired in part by William Catton’s Overshoot. Rather than just focus upon CO2, climate change and the “carbon footprint,” GFN collects, analyzes, and publishes data on all human activities that impact the entire regenerative biocapacity of Earth system, in pursuit of answers to the prime question, “How much do people take compared to what the Earth can renew?” Here, from the GFN website, is a brief summary description of the vital work that their organization does:

Global Footprint Network’s key strategy has been to make available robust Ecological Footprint data. The Ecological Footprint continues to be the only metric that comprehensively compares human demand on nature against nature’s capacity to regenerate. It is based on simple, straightforward accounting – not on arbitrary scoring. Since its inception, Global Footprint Network has calculated Footprints of countries for each year that UN data has been available. Since 2019, these national calculations are produced by York University under the governance of the Footprint Data Foundation (FoDaFo). Currently the accounts cover 1961 to 2022. Together with partners, we, and now FoDaFo, have made every annual edition more transparent and more accurate. This has included rigorous reviews by government institutes and advisory committees, including the Science Advisory Council of FoDaFo.

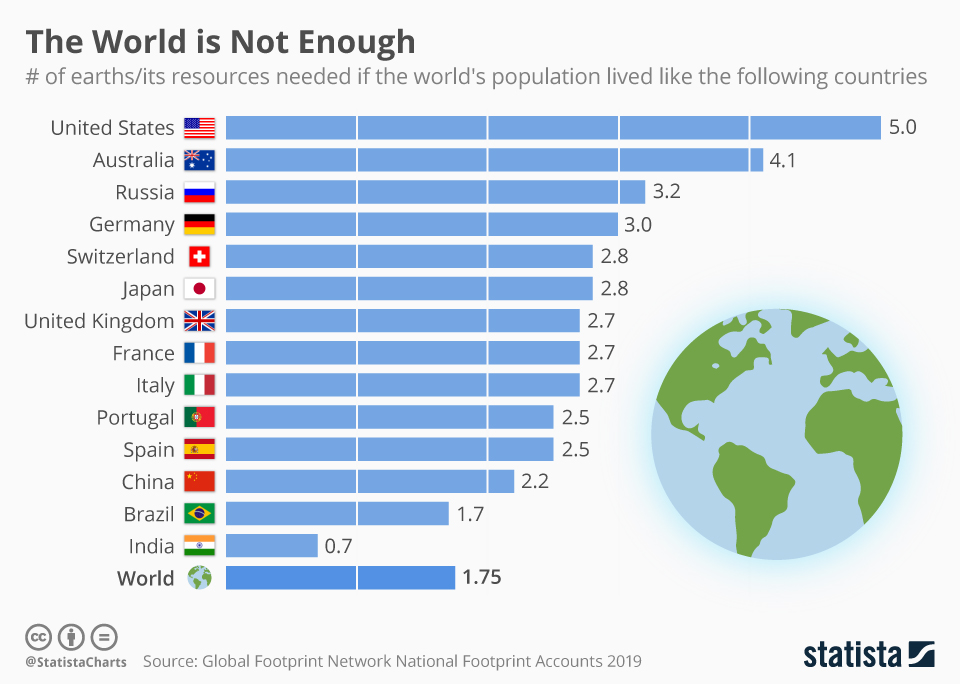

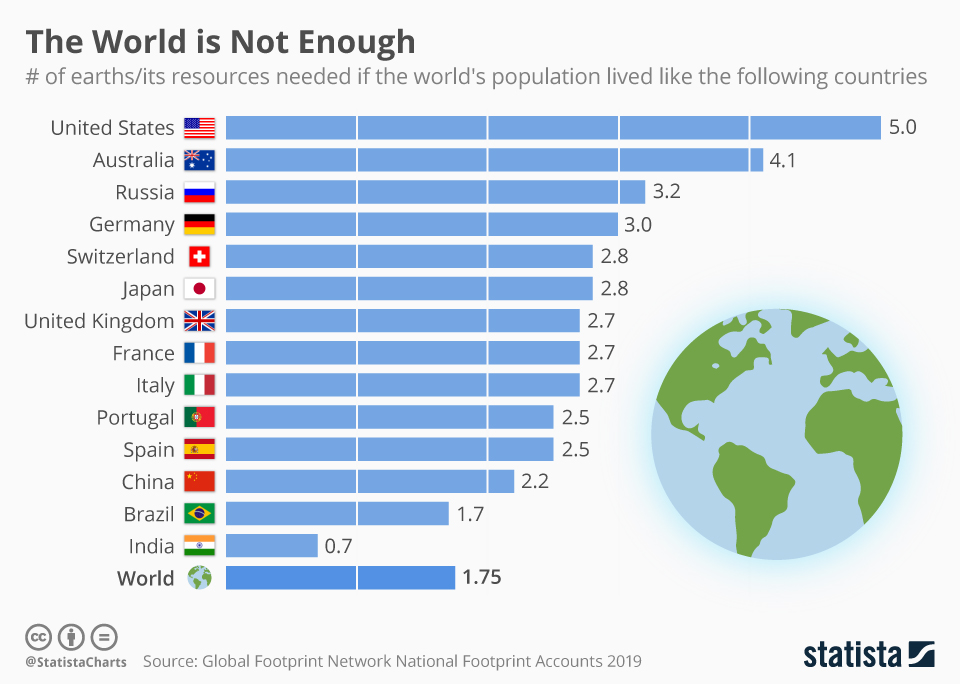

What I find most useful about the work of the Global Footprint Network, for clearly communicating to people the depth of Earth’s current crisis, is their calculations regarding how many additional planet Earth’s we (all of humanity) would need to maintain our current human behaviors, or “ways of life,” and simultaneously allow our biosphere to regenerate its life systems (if that was even possible). Currently, from their 2023 report, the most recent number that the GFN has computed for that is 1.75 planet Earths, for all of humanity combined. What does that mean? When we overshoot Earth’s ability to regenerate at the pace that we are extracting and consuming from her and to process and absorb the many megatons of waste, of all kinds, that we are excreting upon her lands, waters, and atmosphere, biological life on Earth is gradually destroyed. If Earth’s ecosystems are not allowed to regenerate, they then begin to degenerate. Natural life does not remain static. It keeps moving along, fulfilling its particular symbiotic purposes, or it decays and dies (which fulfills another symbiotic purpose, unless deaths become excessive). In light of that biological reality, a vital question that the GFN and other ecological researchers are probing is how much overshoot can our planet and our species take? How long can Earth accommodate our species with an eco-footprint of 1.75, 2.0 or 2.5 Earths?

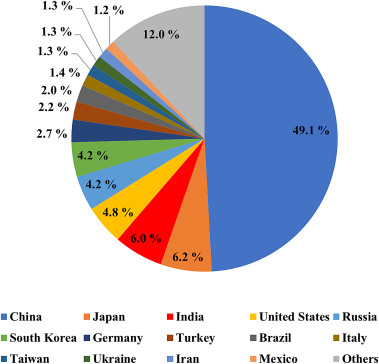

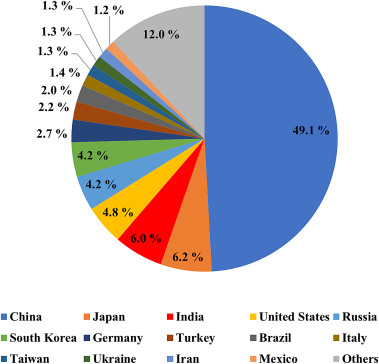

The GFN also has provided us with figures for the ecological footprints of over 200 individual nations, which vary greatly, and the number of Earths needed for the whole world to live in the average manner of the people of each particular nation. Notably, the number of additional Earths needed will always increase, as long as our species continues to live in ways that require additional growth in consumption, production, waste, and population. GFN has compiled and made freely available detailed data on that and many other factors contributing to overshoot, sorted by country, individuals, cities, corporations, and other categories. Here (below) is a chart with summaries of the footprint data from 14 of the over 200 countries studied. The complete list and detailed breakdowns of the data can be found on their website.

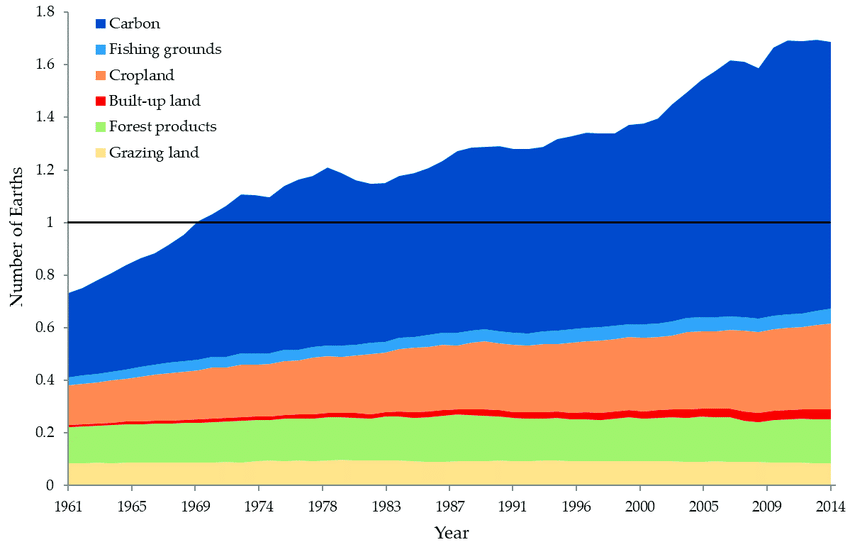

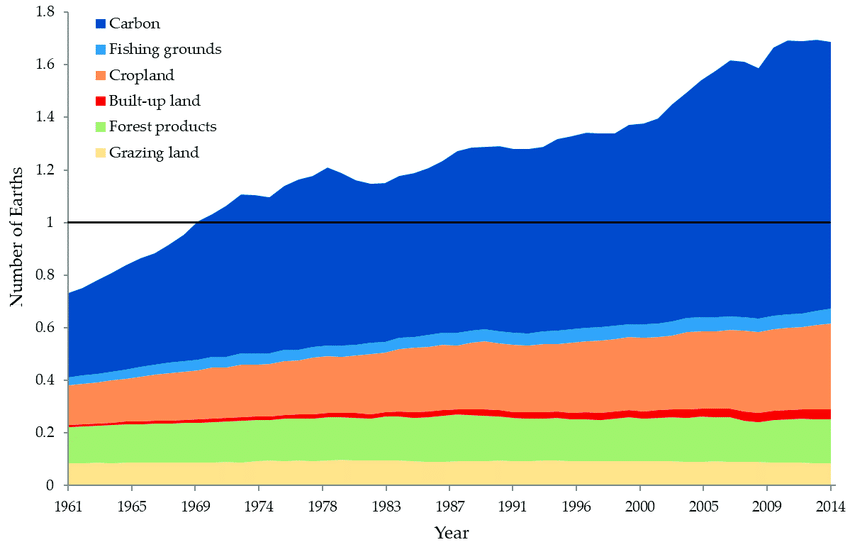

The following GFN chart is a timeline showing at what point our species reached and then exceeded planetary overshoot (about 1969-70), with the types of human over-consumption and excess waste compiled into six, color-coded categories:

While the data accumulated and reported by the GFN is much more extensive and detailed than what appears in that chart, the chart clearly suggests that CO2 emissions are the largest single contributor to Earth overshoot. Industrial petro-chemical agriculture (labeled here as “cropland”) plays the next largest role and the trajectories for both of those contributors continue to rise now, in 2025. Another category of human activity that continues to expand and increasingly contribute to overshoot is the item on the chart labeled “built-up land” (the red section on the chart). It seems that there must be some better label for that, but what “built-up land” refers to is all of the land that is transformed by humans from natural or wild habitat into infrastructure for human social habitat, such as new buildings, paved roads, parking lots, waste treatment facilities, factories, etc. Maybe the phrase should be “additional human infrastructure projects,” or the “de-naturalization of land.”

Seeing on the GFN timeline chart how large a role “Carbon” (the blue area) plays in overshoot, a not-fully-informed, “green” technology optimist might speedily conclude that all we need to do is switch from fossil fuel burning energy use to electric energy devices, in order to live regeneratively, in synch with our one Earth. What is generally overlooked or intentionally ignored by such simplistic, wishful thinking is how much fossil fuel-powered industrial equipment is currently necessary and preferred by industrial capitalists (mainly for competitive reasons) in order to mine the materials, conduct the manufacturing, transport, install, and maintain the enormous “green” energy infrastructure that would be necessary to continue with our unsustainable, over-consumptive, and ever-growing “needs.” Nearly all of the factors contributing to overshoot have been made possible by the enormous industrial, economic and technological infrastructure that has been powered increasingly by fossil fuels over the last 250 years, as William Catton details in his books and we shall discuss further, below. There is a considerable amount of human impact on Earth’s life-giving systems that is not mentioned or accounted for in this chart, like impacts from mining, pollution of surface water sources, and the drawdown of underground aquifers, just to name a few. If those and many other anthropogenic (human-caused) impacts were included in the chart, the blue “Carbon” area would make up a much smaller proportion of the whole, and thereby provide us with a more accurate picture of the causes of ecological overshoot.

The GFN openly acknowledges the gaps and shortcomings in their data collection process, and they say that most of that is due to their long ago decision to rely completely upon United Nations scientific data, in order to avoid suggestions of bias or “cherry picking” data that supports pre-conceived notions. Consequently, another limit that proceeds from that decision is that the UN data only covers impacts from human use demands upon the “biosphere’s (or any region’s) regenerative capacity.” Human demands and impacts upon Earth’s non-renewable or non-regenerative resources found in the geosphere, such as fossil fuels and rare metals, along with many other chemical and mineral entities, are not included in that data set. Neither are the needs of and uses by non-human beings who share the same ecosystems and regions with the humans. The GFN therefore encourages people to look to other research data sources to fill such gaps and they welcome criticism and communication on how they might improve their work. (Ecological Footprint Accounting: Limitations and Criticism, Global Footprint Network research team, 1 August 2020 – Version 1.0) The GFN recently formed a collaborative partnership with York University in Canada which they expect will greatly improve their ability to do more robust research on overshoot and the Ecological footprint and continuously fill more of the data gaps. Regarding the limited data that they have had to work with up until this recent change, the GFN made this potent realization: “…the real biocapacity is even smaller than our estimates. On the Footprint side, not all demands are included because not all are documented in UN accounts. Hence the real footprint is larger.”

Before I return to directly examining William Catton’s books, I will briefly describe another university-affiliated research center with an even larger number of researchers probing into anthropogenic impacts on Earth system that are contributing to overshoot. I am referring to the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University in Sweden. There are many new “climate studies” programs springing up at universities around the world, but the GFA program at York and the SRC at Stockholm are the only two programs that I know of which are focused on Earth system overshoot, instead of just climate. I hope that there are actually many more than just those two, or that there will be soon. Some urgent questions that researchers need to explore and publish data for, ASAP, include:

- How much fossil fuel will likely be burned (globally) in the attempt to mine, manufacture and install so-called “green energy” infrastructure replacements for fossil fuels?

- What is the extent of damage to Earth’s life system, to date and annually, being perpetrated by the mining industry and how much might that increase through a global “green energy” transition?

- What is the extent of damage to Earth’s life system, to date and annually, being perpetrated by the smelting of steel, copper, cement, and glass?

- At current rates of increase in industrial activity, globally, by what near-future year (or decade) will we have made certain that the “Sixth Great Mass Extinction” will occur? (Have we already reached that point?)

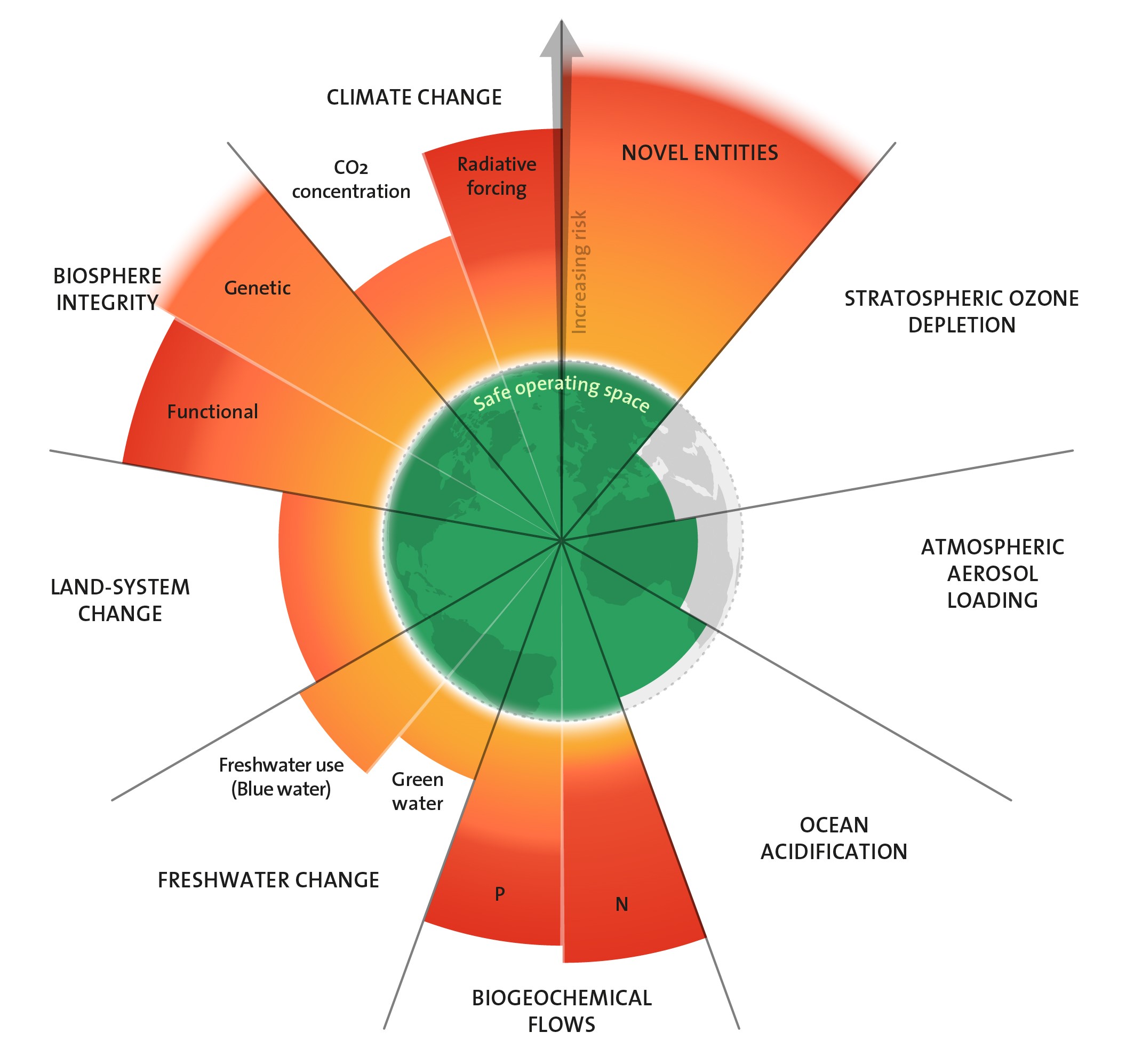

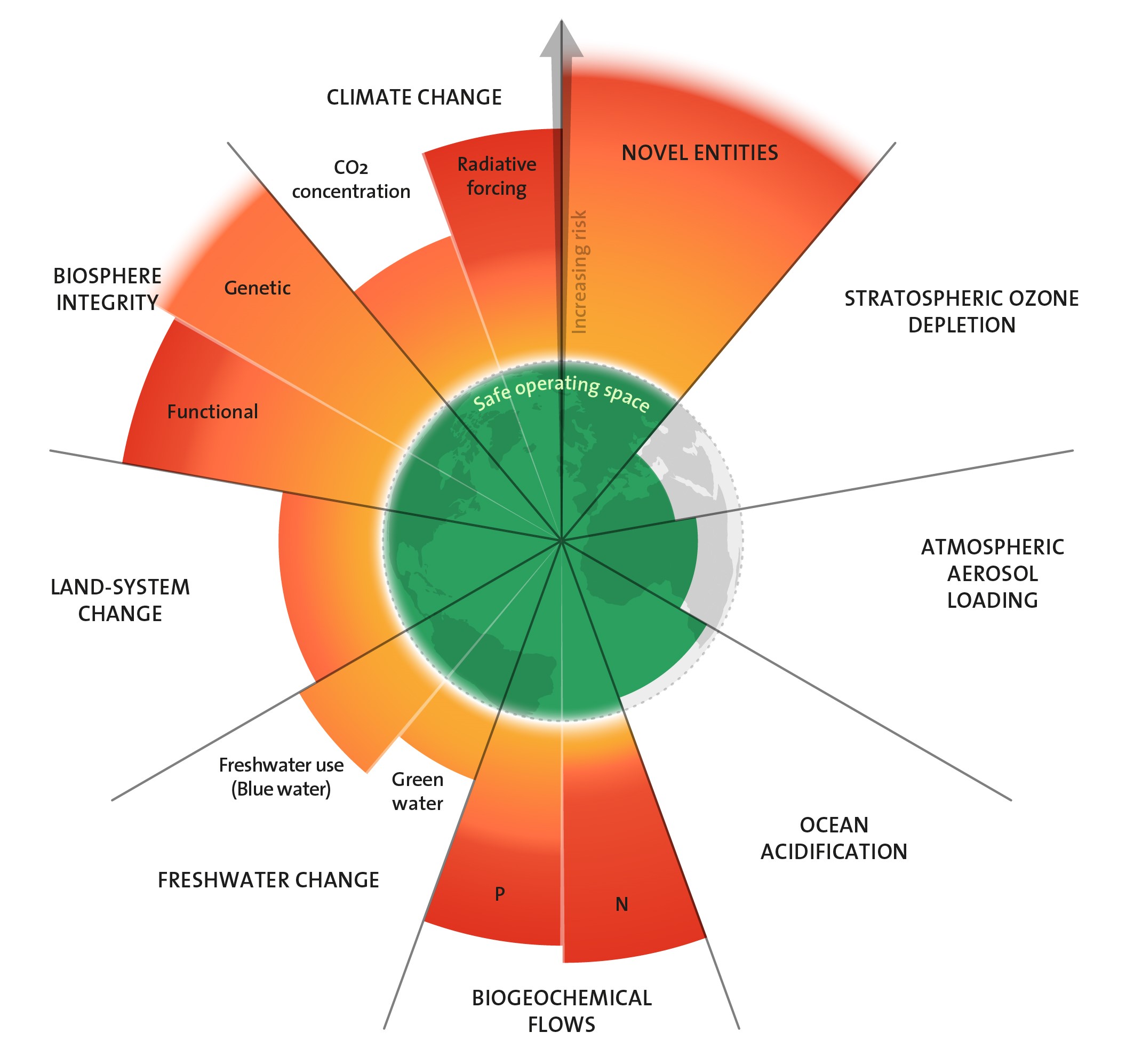

The SRC has identified nine categories or types of ecological processes that “are critical for maintaining the stability and resilience of Earth system as a whole.” Those nine categories, commonly referred to as the “nine planetary boundaries,” are identified in the chart below and defined in detail in their reports. As of August, 2023, SRC research and analysis has found that human activities impacting Earth system have now exceeded what they call “the safe operating space for humanity” in six out of the nine categories. As stated in their 2023 report:

The planetary boundaries framework delineates the biophysical and biochemical systems and processes known to regulate the state of the planet within ranges that are historically known and scientifically likely to maintain Earth system stability and life-support systems conducive to the human welfare and societal development experienced during the Holocene. Human activities have now brought Earth outside of the Holocene’s window of environmental variability, giving rise to the proposed Anthropocene epoch.

Earth system is a dynamic, life-sustaining, regenerative interaction between the geosphere, the biosphere (which includes what we could call the “aquasphere?”), and the atmosphere, along with the vital contributions from the sun and our moon. Before about 1950, humans were simply part of the biosphere, but around that point in time human impact upon Earth system had become so significant that it was (and is now) a powerful force in determining Earth system’s continued functional well-being. Some people (both scientists and non-scientists) now refer to this phenomenal magnitude of impact as the “anthroposphere.” Unlike the other spheres of Earth system, the anthroposphere is much more destructive to life than sustaining or regenerative in its impact. To only assess the well-being of Earth system by measuring the CO2 content of Earth’s atmosphere (as many now seem content to do) ignores and obfuscates the extensive damage being done by humanity to Earth system as a whole. The following recent chart by the Stockholm Resilience Centre illustrates the nine planetary boundaries and does a much better job than the GFN chart above of showing which aspects of overshoot are causing the most harm to life on Earth, and what greater dangers and losses lie ahead:

Credit: “Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023“

Here is a brief summary of the 9 planetary boundaries and how far we have exceeded or are close to exceeding each one:

Biosphere Integrity, Climate Change, Novel Entities, Stratospheric Ozone Depletion*, Freshwater Change, Atmospheric Aerosol Loading*, Ocean Acidification*, Land System Change, Biogeochemical Flows

*= the three boundaries that have not yet been transgressed

1. Biosphere Integrity-

This boundary is perhaps the most significant and also happens to be the one that humans have exceeded to the furthest extent. According to the scientists who authored the planetary boundaries report: “The planetary functioning of the biosphere ultimately rests on its genetic diversity, inherited from natural selection not only during its dynamic history of coevolution with the geosphere but also on its functional role in regulating the state of Earth system. Genetic diversity and planetary function, each measured through suitable proxies, are therefore the two dimensions that form the basis of a planetary boundary for biosphere integrity.” The most obvious indicators of violation of this particular planetary boundary are the rising extinction rate and the loss of biodiversity throughout our planet. According to the authors, “Of an estimated 8 million plant and animal species [other scientists estimate between 9 and 10 million species], around 1 million are threatened with extinction, and over 10% of genetic diversity of plants and animals may have been lost over the past 150 years.” Those facts do not mean much to most modern humans, who are not aware of the symbiotic connections, interrelatedness, and interdependency of all life. Prevailing human cultures tend to believe that life consists of unrelated individuals (among all species) who live in a state of ruthless, predatory competition with each other. The concepts of “survival of the fittest,” unregulated capitalism, anthropocentrism, and racial supremacy are all compatible with that belief paradigm of separateness and disconnection. Scientific researchers recently discovered that the total weight of all of the materials made and currently used by humans (1.15 trillion tonnes) recently surpassed the total weight of all biological life on Earth (1.12 trillion tonnes)! Humans make up just 0.1% of Earth’s biological life, or “biomass,” and we are just one of between nine and ten million different species of animals. What right do we have to extract and reconfigure so much of Earth’s material substance? To return to a way of life that is conducive to biosphere integrity, humans need to find out what would actually be our sustainable, regenerative share of Earth’s material substance and return to a one Earth footprint manner of living.

2. Climate Change-

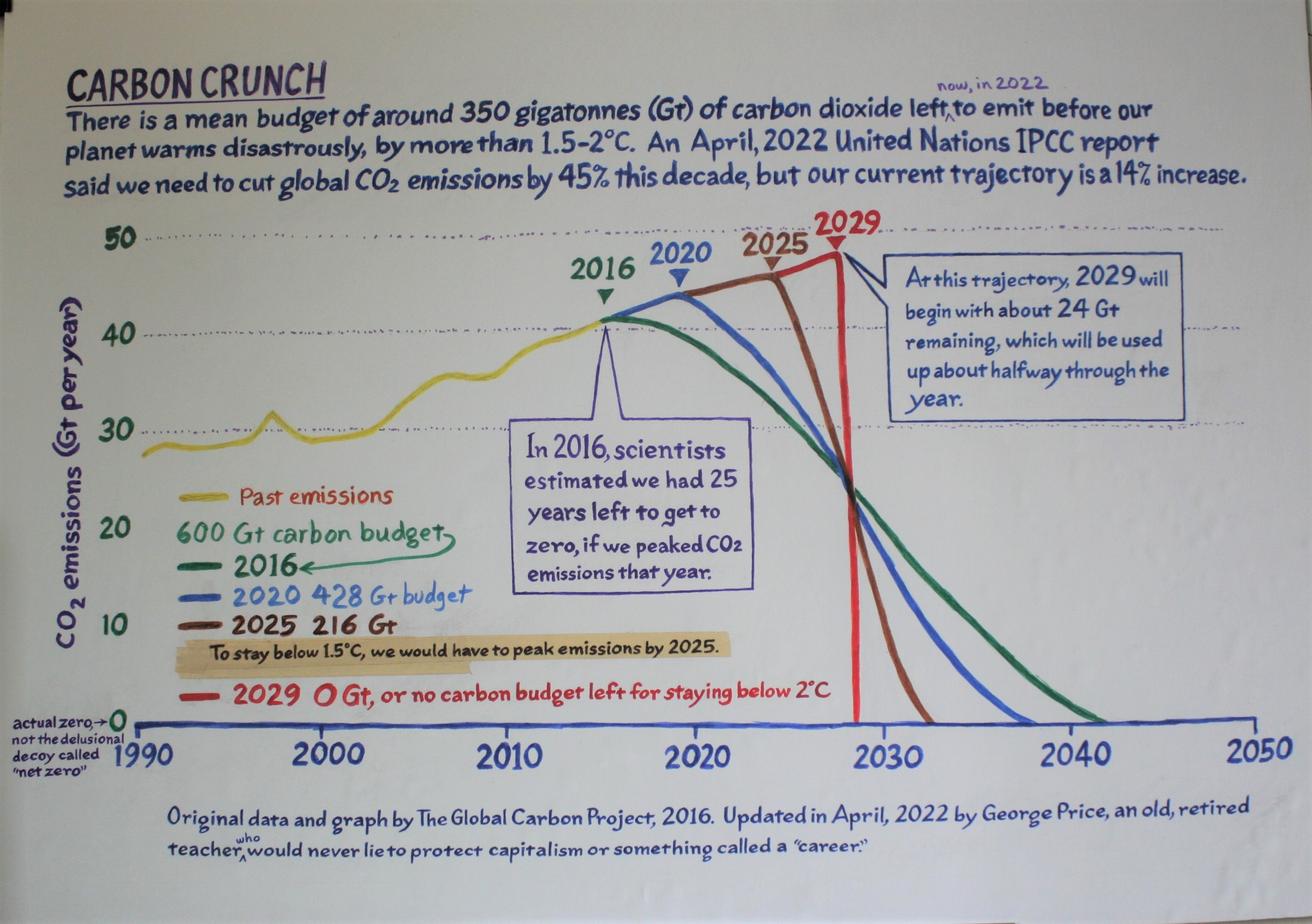

This planetary boundary is currently the most popular, or well-known. For most present-era humans it is the only one of the 9 boundaries that people are aware of or concerned with (with the possible exception of some types of toxic pollution, such as water, air and plastics, which are covered in a few of the other planetary boundaries, such as “Novel Entities” and “Freshwater Change,” as we shall soon discuss). Why are people more comfortable dealing with Climate Change than the other planetary boundaries? Could it be because the capitalists have convinced them that it is solvable through buying more manufactured technological products (solar panels, lithium batteries, windmills, etc.) that would thereby allow them to keep their over-consumptive, addictive way of life?

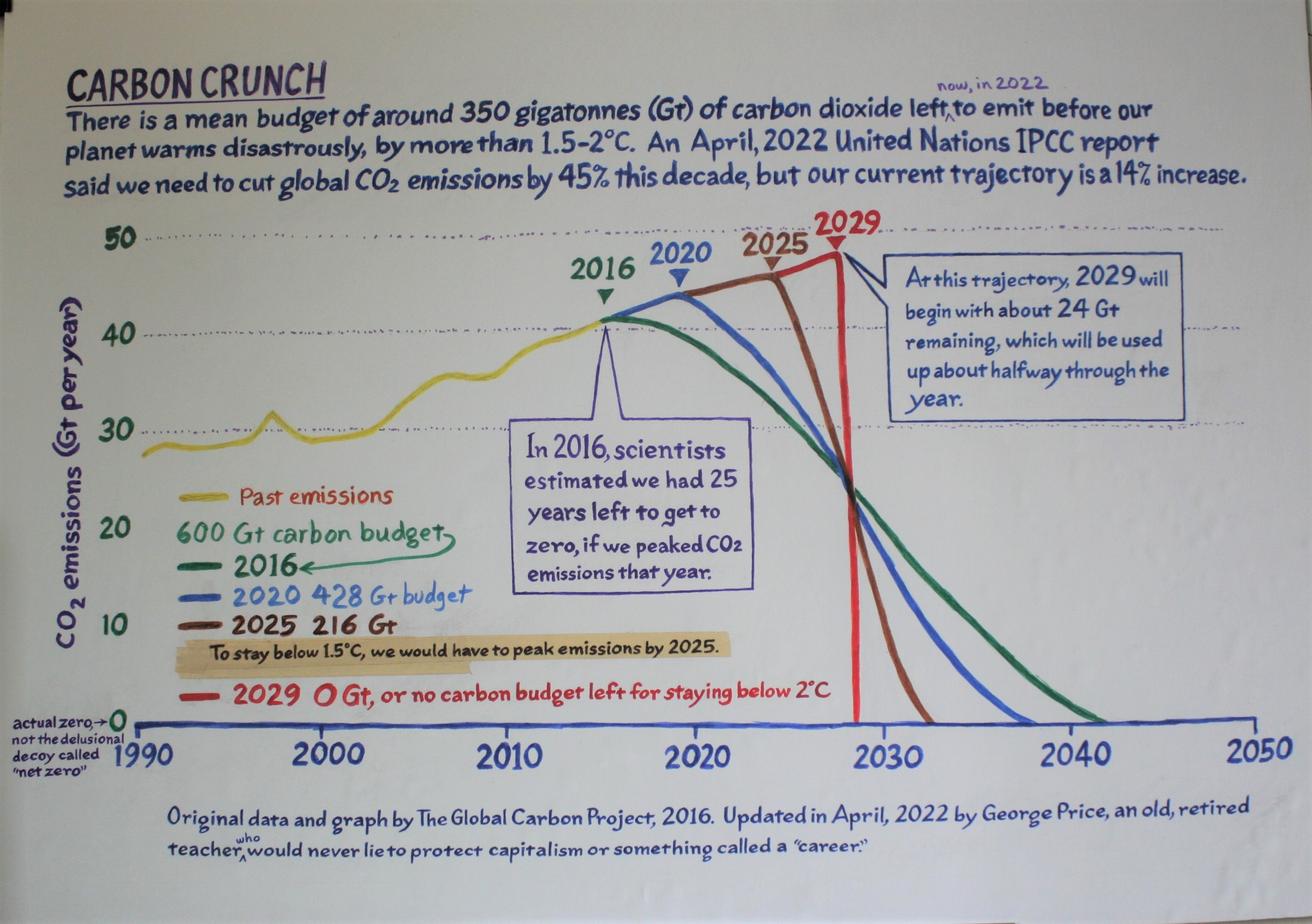

The evidence that we have blown way past this boundary is abundant: 430 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere, and rising, when the safe zone max is 350 ppm; we have surpassed 1.5 degrees C warmer than pre-industrial era avg. temps; breaking more and more temperature records every year; ocean warming; coral ecosystems dying; increasing weather catastrophes and anomalies; loss of habitat forcing migrations and extinctions; permafrost and glaciers melting; sea levels rising; acceleration of symptoms; tipping points, etc.

3. “Novel entities”-

What this boundary refers to is “truly novel anthropogenic introductions to Earth system. These include synthetic chemicals and substances (e.g., microplastics, endocrine disruptors, and organic pollutants); anthropogenically mobilized radioactive materials, including nuclear waste and nuclear weapons; and human modification of evolution, genetically modified organisms and other direct human interventions in evolutionary processes. Novel entities serve as geological markers of the Anthropocene However, their impacts on Earth system as a whole remain largely unstudied. The planetary boundaries framework is only concerned with the stability and resilience of Earth system, i.e., not human or [individual, particular, local] ecosystem health. Thus, it remains a scientific challenge to assess how much loading of novel entities Earth system tolerates before irreversibly shifting into a potentially less habitable state.”

Humans will never be able to create or form something out of nothing, but (unfortunately?) we can extract or gather materials from Earth and transform them into something that does not exist in that form naturally, or without human intervention. Such things are what these scientists call “novel entities.” The creation of novel entities is more impactful than the combining of particular materials commonly used as food in new ways, or inventing recipes. Novel entities are wholly original anthropogenic substances that have been introduced by humans into Earth system that have the potential to alter or interfere with the proper, life-sustaining functions of Earth system and its component ecosystems. Anthropogenic materials that are non-biodegradable are prime examples of that, as are the hundreds of thousands of synthetic chemicals that are routinely produced by human industry and released into the environment. Recent scientific research has revealed to us what might be the most pervasive and highly destructive type of “novel entity” on our planet: PFAS, which stands for Polyfluoroalkyl substances, a combination of carbon and fluorine, the strongest bond in chemistry. PFAS were invented in the early 1940s for the purpose of safely containing uranium in nuclear bombs. They are the most unbreakable, non-biodegradable materials created by humans yet, and so widely-used in manufacturing all types of products, that they have dispersed into air, water, and the bodies of all living organisms. These poisons are also found in our blood, giving us cancers and a host of other diseases. Just like pharmaceutical companies putting new drugs on the market that have not been adequately tested for safety, diverse other industries have long been digging up all kinds of things from under Earth’s surface, combining them, smelting them, and otherwise transforming them into all sorts of unnatural forms, without much regard for potential harm or any respectful consideration of what Earth would rather have us do with those things—like just leave them in the ground where they have always belonged, playing their own particular necessary roles in the functions of Earth system. The belief that there are “things” within or upon Earth’s surface that are “doing nothing,” or are worthless until humans devise some use for them is one of the most significant conceptual errors in the whole history of our species. Along with the conjoined belief that humans can just do whatever they want to non-human “others,” tremendous harm has been done.

I cannot think of any novel entities that are confirmed to be ecologically benign. As the scientists said, “…their impacts on Earth system as a whole remain largely unstudied.” So, it is difficult to assess how far this planetary boundary has been exceeded, but the scientists suspect that the violation has been very substantial, just based on what little we do know about the damage that has been done to life on Earth by these entities, especially PFAS, plastics, nuclear radiation, and genetically modified organisms.

The recommendation of the report’s authors is, “…for novel entities, then, the only truly safe operating space that can ensure maintained Holocene-like conditions is one where these entities are absent unless their potential impacts with respect to Earth system have been thoroughly evaluated.” In other words, don’t mess around with Earth’s gifts without permission from Earth, especially if you have no idea what the heck you are doing, or the harm that the consequences of your actions might cause!

4. Stratospheric ozone depletion-

This particular planetary boundary is the only one that was previously exceeded (about 40 years ago) and has since been corrected to a level slightly below the boundary. According to the authors, “Stratospheric ozone depletion is a special case related to the anthropogenic release of novel entities where gaseous halocarbon compounds from industry and other human activities released into the atmosphere lead to long-lasting depletion of Earth’s ozone layer.” Unlike some other attempts to mitigate exceeding of planetary boundaries, such as using solar panels and wind turbines, the threat to Earth’s stratospheric ozone later was successfully reduced to a safe level without resorting to the use of assumed technological “fixes.” Instead, due to an international cooperative agreement made in 1987, the emissions of gaseous halocarbon compounds was reduced by actual reduction in the use of materials that produce those compounds. The mitigation was accomplished by actually ceasing to continue with the human behavior that created the problem in the first place! What a novel, brilliant idea! Why don’t we try that type of mitigation on the climate problem? The trajectory of release of CO2 into the atmosphere has only moved downward twice in this 21st century: during 2008, when the global economic crisis greatly reduced industrial economic activity, and for a few months in 2020 during the economic activity reduction due to the Covid 19 pandemic. Shutting down and ceasing to continue with toxic industrial activity is the only solution that has proven to work toward reversing (not just slowing down) the rise in atmospheric carbon!

5. Freshwater change-

The planetary boundary called “freshwater change” is concerned with anthropogenic modifications of Earth system functions of freshwater, in particular with deviations from pre-industrial, Holocene era normal extent of variability. The scientist who study and assess this boundary consider changes across the entire water cycle over land. They have divided freshwater into two categories: “blue water” (surface and groundwater) and green water (plant available water found in root-zone soil moisture). “The green water component directly accounts for hydrological regulation of terrestrial ecosystems, climate, and biogeochemical processes, whereas the blue water component accounts for river regulation and aquatic ecosystem integrity. Both components, due to anthropogenic interference, transgressed their planetary boundary safe zones, early in the 20th century. In the United States, before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, it was customary for all kinds of industrial manufacturers to dump their waste materials into nearby rivers, lakes, or the ocean.

6. Atmospheric aerosol loading

Atmospheric aerosols are fine particles of various types in the atmosphere, which, in certain quantities, can impact Earth system. Aerosols occur in the atmosphere naturally, from sources such as dust storms, smoke and soot from forest fires, and ash from volcanic eruptions. Anthropogenic aerosols are the particulate matter cast into the atmosphere by human industrial, domestic, and recreational activities, which includes items like smoke, exhaust, evaporated liquid waste products, dust, and airborne “novel entities.”

One common impact on Earth system caused, at least in part, by an overload of aerosols in a region of the atmosphere is disruptions and reductions in annual monsoon rains. Between 14,000 and 5,000 years ago, the Sahara Desert was a well-vegetated region with forests, wetlands, and many lakes. It is now the largest source of atmospheric dust on our planet, and the least conducive region for supporting biotic life. What happened there? Desertification has both natural and human (or anthropogenic) causes, which can create a reinforcing cycle of feedbacks. The natural ways that can occur include severe drought that causes vegetation die-off, leading to an increased chance of wildfires, which put the aerosols smoke, ash, and soot into the atmosphere. Lack of vegetation (which becomes exacerbated by animals over-grazing the reduced supply) and extreme drying of the soil creates more dust, another aerosol blown into the atmosphere by wind. To complete the cycle, the heavily-increased amount of aerosols in the atmosphere disturbs, reduces, or even cancels the annual monsoon season, leading to more drought, etc. That, along with a little bit of anthropogenic activity, like the use of fire, is probably how the Sahara became a desert.

Since the beginning of the industrial era, a whole slew of additional anthropogenic contributions to aerosols in the atmosphere has led to the desertification of many regional areas around the world. Global heating, as a result of increased CO2, has also played a major role in desertification. Ironically, the increase in aerosol particles in the atmosphere has also had a slight muting effect on the increase in global warming. The planetary boundaries scientists have tentatively concluded that we are still in the “safe operating zone” for atmospheric aerosol loading, while cautioning us that there is much more that needs to be discovered and applied for this topic (such as anthropogenic impacts on the natural production of aerosols). The scientists make many such statements about the uncertainties due to so many unknowns about the interactive functions of Earth system in their discussions of each of the nine planetary boundaries. Earth system science is still a relatively new academic field of study. That makes me wonder if the human species is about to exit the realm of life on Earth just when we are on the verge of learning so much more about how Earth system actually operates. But can knowing, alone, change our ways of being?

7. Ocean Acidification

Ocean acidification is one of the three boundaries that the scientists estimate have not yet been surpassed. Of those three, ocean acidification appears to be the closest to being transgressed next. To measure anthropogenic contribution to ocean acidification, the control variable that the scientists use is the carbonate ion concentration in surface seawater. They tell us that, “anthropogenic ocean acidification currently lies at the margin of the safe operating space, and the trend is worsening as anthropogenic CO2 emission continues to rise.” It was just reported today that atmospheric CO2 just reached 430 ppm. 350 ppm is the safe limit for that, and the trajectory under the machine of industrial technological civilization is continued acceleration.

8. Land System Change

This is the one about the importance of the trees. According to the authors of the report: “This boundary focuses on the three major forest biomes that globally play the largest role in driving biogeophysical processes, i.e. tropical, temperate, and boreal. The control variable remains the same: forest cover remaining compared to the potential area of forest in the Holocene.” Deforestation is the key indicator in measuring that this boundary has been clearly transgressed. One of the best examples is that the Amazon forest recently (2023?) moved from being one of Earth’s largest carbon sinks to now being a source for CO2 emissions. According to these scientists, deforestation has been ongoing in most forested regions on Earth since 2015. With the help of satellite images, which are used to make land cover classification maps, this planetary process is rather easy to observe and analyze. Land use conversion, for industrial and agricultural access to Earth “resources,” and for creation of more human urban habitat, are the primary causes of deforestation, besides the increase in wildfires.

9. Biogeochemical Flows

I will begin this one by quoting directly from the report: “Biogeochemical flows reflect anthropogenic perturbation of global element cycles. Currently, the framework considers nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) as these two elements constitute fundamental building blocks of life, and their global cycles have been markedly altered through agriculture and industry. Anthropogenic impacts on global carbon cycling are equally fundamental but are addressed in the climate and biosphere integrity boundaries. Other elements could come into focus under this boundary as an understanding of human perturbation of element cycles advances. For both N and P, the anthropogenic release of reactive forms to land and oceans is of interest, as altered nutrient flows and element ratios have profound effects on ecosystem composition and long-term Earth system effects. Some of today’s changes will only be seen on evolutionary time scales, while others are already affecting climate and biosphere integrity.”

The greatest harm done by these anthropogenic releases or flows of phosphorus and nitrogen is the eutrophication of freshwater ecosystems. Eutrophication occurs when excessive buildup of nitrogen and phosphorus in freshwater systems generates excessive reproduction of algae and aquatic plants to the point where oxygen is greatly reduced in the water, causing die-off of fish, aquatic insects, shellfish, and many plants. This process has been long in play throughout the world, caused mostly by runoff from chemicals used in agriculture, but also from industrial pollution. Scientists estimate that this planetary boundary has been exceeded globally and in many locales since about 1988 and it is now the second most transgressed of the planetary boundaries, after biosphere integrity. Novel entities is in third place, followed by climate change (fourth), land system change (fifth), and fresh water change (sixth). Of the three planetary boundaries that are still in the safe operating zone, it appears that ocean acidification will most likely become the seventh planetary boundary to be crossed, since it is now just barely in the safe zone. Considering how long it takes for scientific data to be analyzed and results to be verified, along with how rapidly human-caused biosphere degeneration is accelerating, the ocean acidification boundary might already have been transgressed.

Regarding the possibility for mitigation or healing of a transgressed planetary boundary, there is one very important point that we need to be deeply aware of. Due to the interdependent relationship of all nine aspects, or “boundaries,” within Earth’s symbiotic living system, it will never be enough to only mitigate one, four, or even five of the six planetary boundaries that have already been breached. Because of their interconnectedness, and the fact that, as these scientists say, all 9 aspects or processes of Earth system “are critical for maintaining the stability and resilience of Earth system as a whole,” we need to live ways of life that will maintain the safe operating functions of all nine. If our species continues to live in ways that keep us on, or recklessly accelerate, our path of destruction of our only viable planet home, and we eventually violate all nine planetary boundaries, we will not be able to return to Holocene era, pre-industrial safe operating conditions if we only mitigate eight of the boundaries. If we do not mitigate or restore all nine, all of the other boundaries would be affected and eventually atrophy back into their previously transgressed state.

In many scholarly and journalistic articles over the last three or four years, I have observed a steadily increasing awareness about overshoot and the need to greatly reduce and/or abandon much of our production, consumption, and waste, rather than try to maintain current levels or continue to increase them while somehow “switching” to the use of electronically powered technological devices. No matter what we power it with, human overshoot of Earth’s carrying capacities will ultimately lead to crash and mass extinctions, if we do not cease from the behaviors and technologies that generate overshoot. We also have not yet even invented (much less actually produced) the types of electronic technological devices or machines that can “successfully” replace, compete with, or surpass the power density levels that are available to industrial extraction, manufacture, and transport through burning fossil fuels. In an economic system and culture that demands aggressive competition in nearly every human endeavor, and prioritizes competitive economic success over the survival of natural life systems, humans bound to such systems and cultures will continue to use fossil fuels until they simply are no longer available, or their way of life has completely crashed, whichever occurs first. As the crisis of overshoot becomes more acute and undeniable, we shall likely soon see data on our actual predicament published everywhere, along with the predictable, desperate attempts to refute, misinterpret, censor or suppress the information. Unfortunately, human beings who favor beliefs and personal comfort over factual, scientifically-proven reality have an incredible ability to deny just about anything.

William Catton’s transformation into an environmental sociologist

Now, back to Catton and his books (more directly, that is—I actually never really left that). As can be seen in the 2014 GFN chart, it is estimated that we reached Earth overshoot, or what one planet Earth can handle from our unsustainable human behaviors, around 1969. The first “Earth Day” in the U.S. took place shortly thereafter, on April 22, 1970, more as a response to recent horrific incidents of industrial pollution (including the massive oil spill on the coast of Santa Barbara, California in January 1969, and the polluted Cuyahoga River near Cleveland, Ohio catching on fire during the summer of that same year) than any significant public awareness of overshoot. This brings us to some observations about the social, professional and experiential context in which William Catton began researching and writing Overshoot, around that same time. Since no book-length or complete biography of Catton’s life exists, my ability to interpret Catton’s response to that context is limited mainly to what we can find in his own writings and in a few interviews. The most revealing account of Catton’s transition from “mainstream” sociologist to eco-sociologist during the early 1970s was written by himself and published in 2008, in an academic journal called, Organization & Environment. The title of the article is, “A Retrospective View of My Development as an Environmental Sociologist.”

William Catton was a professor of sociology at the University of Washington, from 1957 through 1969, a time of enormous change in U.S. social culture (as it also was in other similar societies), mostly in the area of reassessing and attempting to correct deeply-rooted, long-standing societal injustices. The academic field of sociology was understandably focused on those types of issues, both then and long since then. As awareness and concern for environmental issues rose in the late 1960s and early 1970s, progressive social activists and sociologists who were engaged with the two most vital issues that preceded the environmental movement—anti-racism and anti-war—sometimes suspected that environmental concerns were a distraction from those issues, which seemed so much more important to them at that time. Some people thought environmentalism might even be an intentional decoy devised by their opponents. Besides paranoia, perhaps the primary reason for that was Americans and most citizens of modern western societies during the 1970s, whether on the political left or the political right, were anthropocentric in their world view, as the vast majority still are today. Anthropocentric people see human need issues as being of higher priority than issues concerning the well-being of the vast multitude of other species in the natural world, and they generally fail to understand that the basic, essential biological needs of all living beings who share this planet are symbiotically intertwined. Besides being anthropocentric, being urbanized and alienated from nature leads some people to prioritize human justice and relational issues over seemingly abstract concerns regarding a nebulous something called “nature” or “the environment.” When such people are concerned about environmental issues, they generally lean towards “environmental justice” issues, such as impacts from industrial toxic waste deliberately occurring disproportionately in communities of color. In light of that piece of socio-cultural context, I wondered if Bill Catton had ever been criticized or verbally attacked during those times for his attempts to move the field of sociology in a more environmentally-focused, or at least “environmentally aware,” direction. If such conflict did indeed occur, nothing in Catton’s “Retrospective View” article mentions it, even though he does elaborate upon several reasons why he was compelled to resign from his position at UW in 1970 and move himself and his large family all the way to New Zealand to take up a sociology teaching position there, at the University of Canterbury.

What Catton does make clear in his “Retrospective View” article, is that the late 1960s and early `70s was a time of major change for him, professionally and personally, and that he began writing Overshoot during the three years (1970-1973) that he lived and taught in New Zealand. As Catton described it,

Early in 1970, discouraged by effects of the overgrowth of the University of Washington, where enrollment had doubled since I first came to that institution, and disheartened by adverse social effects of population increase in the Puget Sound region, I resigned from the UW sociology faculty and moved my family to Christchurch, New Zealand, an environment significantly resembling an earlier (less populous) version of western Washington.

While it may be interesting to learn more about those “adverse social effects of population increase in the Puget Sound region” and what specifically bothered Catton most about that, I think that it is more relevant to this book review to probe more deeply into what influenced Catton towards a more eco-centric world view. Bill Catton had long been a “nature-lover” and somewhat of a hobby biologist. During his time in Seattle, he and his family frequently visited and camped in the national parks and forests of that region, especially Mount Rainier National Park, which seems to have been his favorite place (cite interview). As the park became more frequently used by weekend visitors during the mid-1960s, Catton got his work schedule changed so that he could engage in some of his scholarly duties on the weekends and get two or three days off at the beginning of the week to take his family camping at Mt. Rainier when the place was much less crowded. He really enjoyed seeing the carloads of people leaving the park on Sunday, while his family entered and then had the park nearly to themselves. During the last six years of the 1960s, Catton wrote several sociological articles on how people use the national parks and wilderness areas, some of which were co-written with professional foresters and professors of forestry. Besides plunging him into a vast realm of new knowledge and information, those collaborative experiences and explorations assisted Catton in making his transition toward a more ecological worldview.

William Catton’s transition to environmental sociologist completed itself during those three years in New Zealand. In the “Retrospective View” article, Catton describes what he calls his “aha! experience.” It happened in a visitor center in a New Zealand national park. As the Catton family often did in the U.S., soon after arriving in NZ, they began exploring that country’s national parks and always spent plenty of time checking out the educational exhibits in the visitor centers. At Westland National Park, Catton found an exhibit on the topic of succession. Succession is a biological process within ecosystems in which one species in an ecosystem declines in numbers or completely disappears, due to the ways in which the habitat has been altered by the uses and practices of the diminishing species and/or other species, as well. The diminishing species is eventually succeeded by another species, which has found the ecosystem to have become more beneficial for its own use due to the ways in which it was altered by the preceding species. Catton provides his own definitions for succession in the glossaries of both books, but I think that this definition from the glossary in Bottleneck is clearer and more useful than the one in Overshoot:

SUCCESSION: an orderly and directional process of change in the composition of a biotic community, resulting from effects of its life processes upon its environment. As former member species dwindle and die out they are replaced by other species (with access to that locality but not previously living there) which happen to be better suited to the changed conditions.

A natural question for a modern industrial/technological, alienated-from-nature and well-socialized human to ask at this point might be, “what do biotic communities have to do with sociology, which is the study of human societies?” After years of exploring human societies’ impacts on natural places, especially regarding over-population and overuse, Catton was beginning to explore questions about nature’s pressures and limits upon human societies. Bill Catton’s “aha! moment” at the Westland National Park visitor center convinced him that sociologists need to become more cognizant of the fact that human societies are still subject to Earth’s natural laws and limits, in spite of modern humanity’s so-called “technological advances” and displays of alleged “mastery over nature.” In resistance to the conventional thinking of not just a particular academic discipline, but an entire society that evidently believed that humans had transcended nearly all subjection to natural laws and ecological limits and are therefore exempt from any consequences for violating such laws, Catton applied the principle factors leading to succession of non-human species in biotic communities to human societies and their interactions with local ecosystems. Re-examining human social interactions and human history from an ecological perspective can enlarge and improve sociology and bring many vital, big picture connections to any academic field of study.

Sociologists of the 1970s, when examining the reasons for the displacement or extinguishment of many human societies, throughout history—from small villages to vast empires—typically considered the causes to be most commonly related to interference or invasion by another human society. Sometimes, usually in the case of fallen empires, internal corruption among the ruling class was considered to be a prime culprit. Catton considered such analyses to be short-sighted, limited by an unfortunate blind spot within his profession which led to the subject of human community succession being “too long misrepresented in sociological literature as an invader-driven process.” According to Catton, the prevailing understanding among sociologists, that “invaders were imagined to be succession’s driving force, pushing out prior occupants who supposedly might otherwise have thrived forever on a given site” made them “oblivious to the important fact that occupants of a site may make it unsuitable for themselves after a time by the use they have made of it.” Catton summed up his point on succession in Overshoot with the following cogent words: “industrial man’s impact upon his habitat might make it unsuitable for industrial man.” In summarizing his “aha! moment” at the visitor center, Catton said, “It was clear to me now that if a national park could be damaged by overuse, so could a continent—or even a whole planet.” Speaking of the new perspective on sociology that he came to during his three years in New Zealand, Catton describes a “growing conviction that sociology needed to pay more attention to some of the biogeochemical processes and other factors traditionally deemed nonsocial and `irrelevant’ to sociology.” What could be more relevant to sociology than to examine the common social processes by which a society can actually destroy their natural source of life?

It has become increasingly evident over the last twenty or more years, especially in about the last ten years, that Mother Earth will soon have the final say regarding the ultimate destiny of modern industrial technological human societies. Having spent the largest segment of my career teaching the survey course in Native American Studies and living in an Indigenous community for the past 39 years, I came to that conclusion as much through my learnings on traditional indigenous world views as I did through my relatively recent (but enthusiastic!) study of ecological science. I agree with Bill Catton’s view that not only sociologists, but everybody else of all professions should look at the world from an ecological, rather than anthropocentric, perspective (more on this when we get into Catton’s critique of narrow professional specialization in Bottleneck). I put the well-being of Earth’s life-giving system above all else, and I would like to see other humans come to the same view. That is why I need to briefly explain now why I have a little problem, not with Catton’s view on the natural reasons for succession of human communities, but with how insensitively he presents that view to those among his readers who are descendants of human communities that were succeeded by unnatural forces not of their own making, such as colonialism or genocide. Rather than ignore, omit, or deny this problem, I am dealing with it now because I anticipate that many people (especially some of my former students and my grandchildren) might also have a problem about the way that Catton says some things, along with some important things that he omits saying (which young “woke” people would expect and almost require him to mention), and I do not want that to keep them from reading his books.

It seems to me that, while “swinging the pendulum” in this other direction, away from the usual emphases within sociology on succession of human communities being the result of brutal or unjust treatment of the prior inhabitants of a place by a succeeding community, toward a more ecological explanation, Catton made a very common human error. He did not acknowledge any points at which the views of those whom he was correcting were also correct. For example, often in the course of history the succession of a human territory or homeland by another group of humans was indeed due to the processes of brutal, violent invasion, colonialism, and other forms of injustice. Acknowledging some points at which opponents in a debate are correct usually helps to build a stronger and more persuasive argument, and I think that William Catton likely knew that. So, I wonder why he did not acknowledge that particular, rather obvious point in his book. Did he not realize that by doing so he could possibly make it more likely that other sociologists, many faculty in other fields of study, many students and many non-academics who held similar views of history (critical of prevailing power structures and practices) would listen to his own views? I wonder if Catton was even concerned at all with changing anybody’s mind or winning anybody over to his way of thinking, or did that seem pointless to him in the face of what he may have perceived to be an inevitably doomed society? These questions and issues arise again during his historical discourse regarding what he calls the “cornucopian myth” and also in the section on “cargoism.” Other than those matters, I really have no problem with Catton’s books, except for what I perceive to be his failure to adequately address capitalism’s role in creating the present global ecological crisis (more on this later, as well). I expect my young friends might also have a little problem with Catton’s repeated use of male pronouns, such as “mankind” or “man” to refer to all humanity as a species. Maybe they can find it excusable as merely a product of the culture and era in which Catton was raised, realizing that most other writers from that era, including some with whom they may agree or admire, also used the same linguistic practice?

The “Cornucopian Myth”

Through the concept of the “Cornucopian Myth,” William Catton provides some social and ecological history of the roots of overshoot, or how we arrived at our present global predicament (some possible answers to question number 2 at the beginning of this book review essay, “How did we arrive at our current predicament?”).

Old Mother Hubbard

Went to the cupboard

To give her poor dog a bone.

But when she got there

The cupboard was bare

And so the poor dog had none.

Many (probably most) people in the affluent societies of this modern industrial, technological, over-consuming world have never experienced a completely bare food cupboard or a totally empty refrigerator, except as newly-purchased furniture. Whenever the supplies become low, even just low on a few essential items, these people have ways to go out and purchase or acquire not only the items in short supply, but usually a few other desired non-essential items, on impulse. Such repeated experience of endless supply, combined with a lack of experience of destitution, helps to create and sustain a grand delusion within modern human minds of infinite supply on an actually finite planet. But, beyond individual personal experiences, the grand delusion of this “cornucopian myth” is also something that we members of modern affluent societies inherited from thousands of years of societal “wrong turns,” and misguided thinking that created ruptures and complete breaks from previously harmonious, or at least sustainable, relations with various ecological homelands. Catton also elaborates on how the cornucopian delusion was helped along by the use of some artificial, temporary and unsustainable extensions of local carrying capacities, such as: taking over other people’s homelands, dependence on trade and imports, and monoculture agriculture.

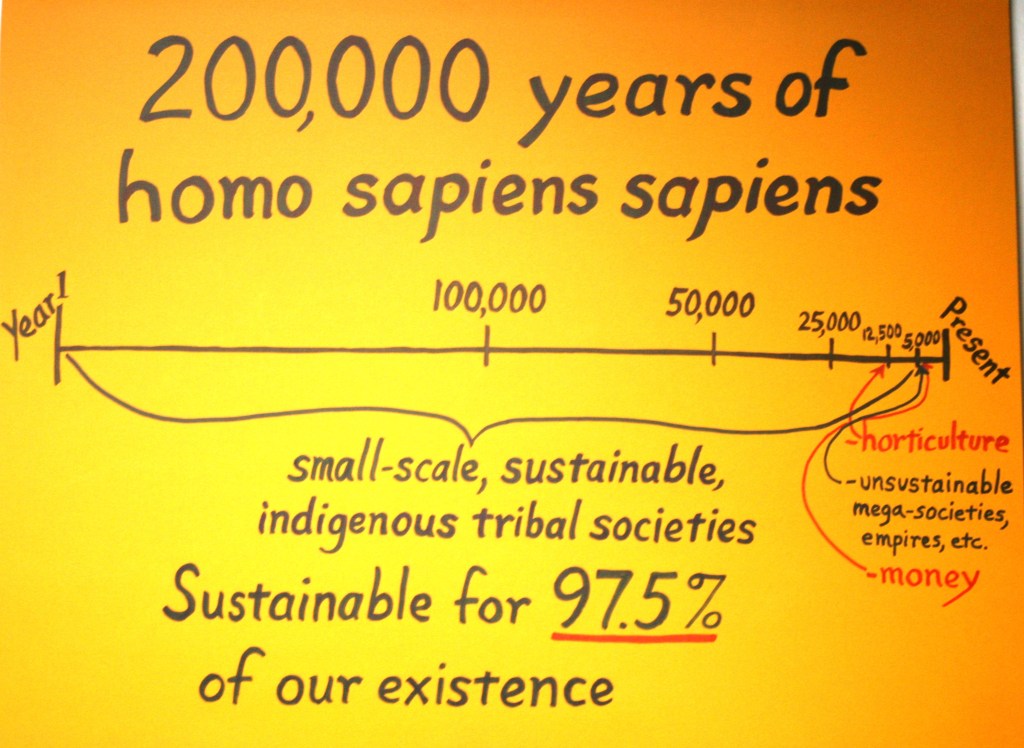

I will say more about the thousands of years of delusion later, but in Overshoot, William Catton is more focused on just the last 500 or so years of delusion-building. One notable exception to that is found in chapter 2, “The Tragic Story of Human Success,” in which Catton points out that the greatest expansion of human population occurred between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago, after humans discovered the ability to cultivate plants from seeds and eventually turned that discovery from permaculture and subsistence horticulture into agriculture. During that period of time, the human population multiplied by a factor of ten, from approximately 8,000,000 to nearly eighty million. Although the development of agriculture was an extremely significant step towards promoting human hubris and anthropocentrism regarding our place and our powers within Earth system, it was not humanity’s first experiment with “managing a portion of the biotic community,” as Catton claimed. Long before the advent of agriculture, human “hunter/gatherers” (a.k.a., “foragers”), in all ecosystems of the world that they inhabited, had already developed some considerable methods of habitat and species “management,” which they combined with their practices of symbiotic co-usage with the other species. Examples of pre-agricultural biotic management include: groups of hunters pushing herds of prey animals into traps for selective culling of those herds; controlled burns in both grasslands and forests, which (after the rains) created fertile grazing lands of fresh, high-protein grasses, preferred by many prey ungulates, and thus simultaneously creating more likely areas for easier hunting; maintaining regeneration and availability of many “wild” (not planted by humans) plant foods and medicines through various selective, careful, and respectful gathering practices; along with many other small eco-footprint habitat “management,” or, “engagement” practices. I do not blame Catton for not knowing all of that, since he was not an anthropologist and even most anthropologists of his era had very little accurate information at all (and even less understanding) about Indigenous and early human cultures, beliefs and practices.

Another important point that needs clarification is that when humans first took up the practice of subsistence horticulture, at the various times and locations, they continued with hunting and gathering while just supplementing those traditional practices with small-scale, subsistence cultivation of crops. While the proportion of subsistence gained through cultivating plants increased more rapidly in some places than in others, early humans, generally, did not make a sudden switch from foraging to exclusive or predominant use of agriculture (contrary to what Catton suggests and many others still assume). Such combined methods of subsistence continue among many Indigenous peoples to this present day.

So, when and how did the cultivation of food plants become a problem? At various points along the way, over these last 10,000 years, some human communities exceeded the amount of cultivation that was sustainable or regenerative to their home ecosystems, at which point horticulture, or something like “permaculture,” morphed into agriculture. Those points in time roughly coincided with three other major wrong turns for humanity: loss of appreciation for our symbiotic interdependence with other species on Earth’s system; dependence on long-distance trade; and the advent of money. All three of those wrong turns, combined, spawned the commodification of the natural world. Humans tend to protect and preserve whatever they depend upon economically. When a human society is economically dependent on maintaining a generously life-supporting, symbiotic, regenerative relationship with their local ecosystem (homeland), then that is what those people will care about most and seek to preserve and protect. Human societies that depend on artificial, unnatural, monetary and trade-based economies will care most about and seek to preserve that.

As new technologies made the artificial, unnatural and anti-natural ways of living easier (including agriculture, but not just that), humans became more dependent upon and more likely to protect the new status quo activities made possible by each new technology. The new ways of thinking and living generated by those early wrong turns created wealth and power imbalances, including the creation of nation states, empires, colonialism and capitalism, which also forced many traditional, ecosystem-based early peoples into submission to the new human systems. When fossil fuels came into common usage, especially within agriculture in the 20th century, the ecological problems resulting from commercial agriculture increased rapidly. A notable example is how the increased application of plowing massive tracts of land, enabled by the new fossil fuel-powered tractors during the 1920s, contributed to the “Dust Bowl” disaster in the 1930s American Midwest “farm belt.” It must also not be forgotten that, about 40 years prior to the advent of the gas engine tractor plow, those lands of the Great Plains had already been severely degraded by the genocide and removal of the American Bison, who had played a major biological role in the natural regeneration of those lands for many thousands of years.