Paths Forward: In Defense of “Utopian” Creativity (last edited and updated, 03-18-2023)

(A helpful note for the reader: To read an endnote click on the number one time. To get back to the place in the text, click on the number again. Hyperlinks can be clicked on and then opened in a new tab.)

The oral traditions and origin stories of many Indigenous peoples, worldwide, include some stories of the endings of previous worlds. In such stories, the end of one world usually coincides with the beginning of a new world. Typically, the end of one world is the end of a grave error, the end of a world gone wrong. The life-endangering wrong way had to end for life to continue anew.[1] To have a fresh start, venturing into many unknowns, might be somewhat scary, but it is really a wonderful gift.

In the early winter months of 2014, in Missoula, Montana, I was part of a coalition of climate activists and Indigenous Earth and water protectors who were trying to stop, or at least discourage, the transport of enormous pieces of mining equipment to the tar sands in Alberta, Canada, where it would be used in the largest and dirtiest oil extraction project on our planet. The equipment was so large that the companies that owned those things could only move them through cities in the middle of the night, at the time of least traffic use (around 2:00 a.m.). They could not transport these monstrosities on the freeways because they were too tall—even lying down on trucks—to go under the overpasses. We called them the “megaloads.” On four cold winter nights, in January through March, we walked out onto the largest street in Missoula as soon as we saw a megaload and its entourage of pilot cars and police vehicles approaching. We sang and round-danced in the middle of the street, carrying signs, and sometimes our crowd was big enough to make a circle that fit from curb to curb across the whole street. The police allowed us to continue for a short while (the longest time was 22 minutes), then they cleared us off the road. A handful of our people intentionally got arrested, but most did not.

Sometime after the fourth megaload blockade, the oil and equipment transport companies decided to refabricate the equipment for transport on the freeways. We had caused them a minor inconvenience and a little negative publicity regarding the tar sands industry and its impacts on the Canadian boreal forests, rivers, the health of humans and other species, and global warming. So they began transporting their destructive devices in smaller pieces, to be reassembled upon arrival in Alberta. That change in operations cost three companies (Exxon Mobil, Imperial Oil, and transport company, Mammoet) about two billion dollars altogether, or about one quarter’s profits (at that time, just before oil prices dropped and tar sands extracting became a little less profitable). When taking government subsidies and tax breaks given to oil corporations into account, they probably hardly even felt a pinch from our annoying actions and were actually able to expand their tar sands operations and increase their profits for a few years after the blockades. Our blockade coalition held together for a few months longer, waiting for the next megaload to come through Missoula, which never came.

During those weeks and months after the last megaload blockade, I spent a good amount of time analyzing and reassessing the value and effectiveness of street blockades and similar actions on the big picture. The big question on my mind, and in the minds of some of my friends, was, “What did we accomplish and what good did we do for protecting the Earth through our actions in the street?” We also wondered who even noticed what we did (most citizens of Missoula are asleep at 2:00 a.m. and we didn’t get much media coverage) and, for those that noticed, did anybody who wasn’t already in agreement with our views on protecting the natural world change their minds and decide to take action on behalf of natural life? How about the megaload transport workers, security guards and police, whom we forced to stop their work and sit there watching us for 15 or 20 minutes, reading our signs, and listening to our round dance songs and our vocal pleas for the end of fossil fuel use? Did any of them change their thinking or quit their jobs? Well, we never heard back from any of them on that, as far as I know, seven years later.

One thing that seemed pretty certain to me then, and I’m even more sure about now, is that humans who live in monetary-based economies (capitalist or socialist) will very rarely choose to cease engaging in activities that assure them that they will be rewarded with that most essential material tool: money. That includes fossil fuel workers, the corporate bosses who own their labor, and just about everybody else who lives within the constraints of modern industrial societies. Most people would not knowingly engage in toxic, life-destroying activities if they were not getting paid for it or benefitting from it in some other way, or if they did not feel that they had no choice other than to make money doing such things. As long as people are rewarded for destroying life on Earth, they will continue to destroy life on Earth. Just about a week before the first megaload blockade, in January, I had written an essay about how money and beliefs about money are at the root of all of the activities, systems, and structural devices that are destroying natural life on Earth, titled, “The Problem with Money.” In the months after the last blockade, I revised that essay into a new one, titled, The End of Money: The Need for Alternative, Sustainable, Non-monetary Local Economies , and began to bring the ideas therein into many public forums, mostly attended by other self-professed “environmental activists.” That essay is a combination of critique of the status quo and suggestions for alternative, EarthLife-centered, local economies and societal structures. At that point in time, I had come to the conclusion that it was futile to continue attempting to change the prevailing large-scale societies (nation states and corporate-controlled empires), working through the usual channels, and settling for the small increments and ineffective gestures toward change allowed by the systemic authorities.[2] As I was learning more about the science regarding Earth’s bio-system tipping points and feedback cycles, I could see that we most likely do not have the time to move at such a snail’s pace, “barking up the wrong trees,” and make the types of major changes in human activities and social systems necessary for stopping the destruction of our interconnected Life on Earth and preventing more mass extinctions and ecosystem collapses. It had become clear to me then, and it is even clearer now, that the actual function of our political and economic systems is to perpetuate and protect the productive and consumptive mechanisms and so-called “way of life” that is destroying life on Earth, regardless of any official statements of purpose or intent to the contrary. As a professional historian and long-time social activist, I see two primary purposes for most human political governments throughout history: 1) to protect the property, wealth and power of the ruling elites, 2) to keep everybody else compliant with the prevailing social system (whether through threats to their safety and well-being, or by small gestures of appeasement that generate pacifying and delusional hopes and beliefs in the system).The response that I received from most people to all of that was disappointing, but also enlightening. For a variety of understandable reasons, many people feel an immediate need to dismiss and block out not only the essay, but my entire perspective on necessary responses to our current crisis as “utopian dreaming,” or some similarly dismissive label.

When people read that essay or hear me say things like the economic and political structure of modern industrial societies is fundamentally wrong and that these societies must end most of their ways of being before they destroy most life on Earth, there are two responses that I hear most frequently, from the very few people who bother to talk with me about these ideas at all. Here are those responses:

“You are throwing out the baby with the bath water!”

“You are making the perfect the enemy of the good.”

My succinct reply to that first dismissive accusation can be found in the very short essay on this blog titled, “Who is the Baby?” That reply basically goes along the lines of asking people which baby they want to save, industrial civilization and their modern conveniences, or natural biological life on Earth, because we cannot save both. That is all I will say about that one now, as the point has also been made in my book review of Bright Green Lies, even better in the Bright Green Lies book itself, and by many others, including more and more climate-related scientists. (I will elaborate on this further, below). In this present essay, I would like to focus on that second dismissive accusation, which was actually the primary impetus for me to write this essay in the first place, along with my love for natural life.

There are many important questions to probe about the assumedly “perfect” and the allegedly “good.” Why do most people believe that utopian thinking is a quest for “perfection?” How did that claim originate? Whose interest does the claim that all utopian thinkers are unrealistic, irrational perfectionists serve? What is the difference between an imaginary, unattainable, “perfect” society and an ideal society? Are the societies that we (residents of all modern industrial nation states) live in now something that we can justifiably call “good?” When we call societies like these “good,” do we really mean that they are “lesser evils?” Very often, when people are told that their society is not good, or is unjust and harmful to life, they respond by comparing it to some other countries that they consider to be much worse. Is “good” and “lesser evil” truly the same thing? What should be the essential, required elements for a truly good or ideal society, especially in light of the current and near-future global crises? I would like to productively address all of the above questions in this essay and, by doing so, hopefully open up some possibilities for future interaction and deeper engagement with these core issues. Ultimately, I would like to persuade people that utopian thinking and actual creativity really is a useful, vital and even absolutely necessary exercise for us to engage in now, in order to be able to proactively and successfully deal with the challenges presented to us by the current and future, multi-pronged crises facing both Earth’s biosphere and the prevailing human societal frameworks.

Obviously, answering these questions will require some clarification of the definitions of several terms, especially “utopian.” So, in the interest of getting right to the point, let’s begin with that word. The word, “utopia,” was invented by Thomas More (Sir or Saint Thomas More, if you think that we should use one of those two titles that were bestowed upon him by the recognized authorities, when speaking of him), for his 1516 novel, “A little, true book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, about how things should be in a state and about the new island Utopia.” That was the original, long title (but in English, instead of the original Latin). There are six slightly different shorter titles used in some of the various English translations of the book, as follows:

- On the Best State of a Republic and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Highest State of the Republic and the New Island Utopia

- On the Best State of a Commonwealth and on the New Island of Utopia

- Concerning the Best Condition of the Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

- On the Best Kind of a Republic and About the New Island of Utopia

- About the Best State of a Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia

Why was it important for me to show you More’s actual original title of the book and the six commonly-used titles? Because none of the titles describe the fictional island nation called Utopia as “perfect” and the book is not a discussion of perfect societies at all, but rather of best or most optimal societies. More uses the word “perfect” six times in the book, but never as a descriptive term for Utopia. [3] Rather than calling Utopia perfect or flawless, More preferred words like “best” or “good.” In his original title, More suggests that Utopia is an example of “how things should be in a state,” or, in other words, an ideal—but not perfect—state. The word “best,” in the 16th century as well as now, is a relative term, defined as “better than all other examples of a certain type or class of thing.” Under that general definition, the thing referred to as best is also understood to be the best so far, or best that we know of, until something better of its type is either found, accomplished, or created. In no way is the best considered to be permanently best, flawless, without room for improvement, or perfect.

The meaning of the word “best” in the various English titles of the book, as outlined above, becomes even clearer when we consider the structure and style of this frame narrative novel. The book is divided into two parts, the first part being a discussion between More and a couple of fictional characters about both the flaws and the best aspects of European societies, including England, and the second part is a descriptive narrative by one of More’s fictional friends about a fictional island somewhere off the coast of South America called “Utopia.” [4] Much of the social structure, politics, economics (i.e., no private property in Utopia), beliefs and customs of Utopia are compared to those in Europe and found by More’s friend to be ideal, or at least better than those in Europe. But, not only does no character in the story assert that Utopia is perfect, More himself, as a character in his own novel, states in conclusion at the end of the book that, when listening to his friend describe Utopia, “many things occurred to me, both concerning the manners and laws of that people [the Utopians], that seemed very absurd,” and, after listing some of those disagreeable aspects of Utopian society, he says in his final sentence, “however, there are many things in the Commonwealth of Utopia that I rather wish, than hope, to see followed in our governments.”[5] The literary device that More uses here, in which he places himself in conversation with the fictional characters that he created (his “imaginary friends?”), allows him to express ideas that might have been dangerous for him to propose directly, in his own voice, while representing himself as somewhat oppositional to the radical social ideas advocated for by the character who describes Utopia, Raphael Hythlodaye. This technique also allowed More to be somewhat mysterious, or publicly ambivalent, regarding his actual views about ideal societies (“plausible deniability”?), as he was considering finding employment in the court of King Henry VIII at the time when he was writing “Utopia.”[6]

For the record, and to be absolutely clear, as I see it, and I think most of my readers would agree, Thomas More’s Utopia is no utopia or ideal society.

For the record, and to be absolutely clear, as I see it, and I think most of my readers would agree, Thomas More’s Utopia is no utopia or ideal society. Even though the Utopians have an economic system that is somewhat ideal and closely resembles the non-monetary, use value (rather than market or commodity value), need-based distribution, gift economy type of economic system that I and others have long advocated for,[7] much of the rest of Utopia’s social order is abominable. For example, it is a patriarchal society with all of the political leaders being males, and the Utopians allow for and excuse colonialism and slavery (not race-based, but for convicts and prisoners of war). While they seem to keep their population within the carrying capacity of their island most of the time, when their population gets a little too large for that, they form temporary colonies on the neighboring mainland, with or without the permission of the people already living there, on lands that they call “waste land,” because the land is uncultivated or “undeveloped” by humans (a familiar excuse used frequently by European colonialists of the western hemisphere, in More’s time and long after). That perspective and practice also illustrates the crucial missing element of the Utopian economic system, which (if it actually existed) would doom it to unsustainability and failure: it is anthropocentric, or centered on human needs and desires only, and not on the needs and sustainable, regenerative order of their local ecosystems, including all species of Life. That has been the most significant flaw of most utopian communal experiments in western, Euro-based societies for centuries (a point that I will elaborate upon further, below).

One reason for the common claim that the Utopia in More’s book, or any proposed utopian society, is intended to be perfect and therefore can never actually exist, can be found in the debate over More’s intended meaning of the name. Thomas More invented the name, Utopia, based on one of two possible Greek prefixes. (The suffix is “topos,” which means “place,” and there is no debate regarding that.) The debatable possible prefixes are “ou” (pronounced “oo,” as in “boo” or “goo”), which means “no,” or “none,” and “eu” (pronounced like “you”), which means “good.” Depending upon which Greek prefix one thinks More incorporated for the name of his fictional society, Utopia can either mean “No place,” if the prefix came from ou, or “good place,” if it came from eu. The U in the word Utopia has long been pronounced like the Greek eu, which suggests that More possibly used that prefix to form the name, but, since we have no audio recordings of how utopia was pronounced by More and other early 16th century English speakers, we don’t know with any certainty that they pronounced it in the same way that we do now. The text of Utopia itself, was originally written in Latin by More (who left it to later, posthumous publishers to produce English translations), not Greek, so there is no assurance there as to which Greek prefix he meant. “Utopia” is the Latin spelling of the name. For some reason, possibly related to his personal career ambitions and even his personal safety (in a society in which people often unexpectedly or capriciously “lost their heads”), More left the question about the meaning of “Utopia”—no place or a good place—open to debate. There is a contextual clue on page 171 of the second English translation, but it does not definitively resolve the question. [8]

So, now we can leave that question of the origin and meaning of the word behind us and get to the more important question of why most people believe that utopian thinking is a futile, foolish quest for “perfection.” The short, most direct, and most likely answer is because that is what they have always been told. But, if that is not how the inventor of the word defined it, who decided to give us this other story, and why? Follow the interest and the benefit (not just the money). The powerful and wealthy, the rulers of the vast majority of human societies, find it in their interest to discourage their subject people from imagining or creating alternative societies that are no longer subject to their domain and no longer contribute toward generating enormous, disproportionate amounts of material wealth for themselves. Ever since human beings began to depart from living in local, indigenous, eco-centered, life-regenerating communities and started creating unsustainable mega-societies like nation states and empires, about 7,000 years ago, the rulers have worked hard (or hired and forced others to work hard) at producing and perpetuating many lies for the purpose of deluding or frightening their subjects into remaining submissive to their systemic power, wealth and control. Over this long span of time, the rulers became very adept at persuading people what to think and what not to think, and with the electronic technologies invented over the last hundred or so years,[9] the subjected general public has been constantly bombarded with such messages. Commercial advertising, mandatory public schooling, peer pressure, parental love, fear of poverty, and the quest for equality, along with many other things, have all been used successfully by the ruling class as mechanisms for keeping people submissive and keeping wealth and power in the hands of a select social minority.

One of the saddest things that I have ever seen is children being taught to censor themselves from asking legitimate, important, and even vital questions, especially the big questions about the often illogical, counterintuitive and clearly unjust societal structure and traditions.

Not only are we told what to think, but also which topics to never think about seriously and which questions are too dangerous to ever ask. One of the saddest things that I have ever seen is children being taught to censor themselves from asking legitimate, important, and even vital questions, especially the big questions about the often illogical, counterintuitive and clearly unjust societal structure and traditions. The topics that the rulers would like to see eliminated from our thoughts and plans the most are those that threaten to end their power, wealth and social control. Thoughts, plans, and especially actions, for creating ideal, utopian societies must therefore be suppressed and eliminated, and the most effective mechanism used for that purpose, so far, has been to convince people that utopian societies can never exist because utopia means “perfect” and we all know that humans are not, have never been, and will never be, perfect. It would be much harder for the rulers to convince us that we can’t become something much better than we are now, not just individually, but collectively, as a society, and therefore they cannot allow “utopian” to be defined as “better” or “best possible,” as the title and discourse in Thomas More’s book seems to suggest.

The more that subject people are rewarded, praised, honored, and awarded for their submission and service to the rulers and the system, the more difficult it becomes for them to question and resist the status quo. When the status quo systems are completely accepted as at least inevitable (“the only game in town”), if not unquestionable, and people are convinced that any apparent flaws in the system will eventually be corrected by the system, utopian creativity becomes unnecessary, dismissed, and considered a foolish waste of time and energy. Thoughts about reform—improving the system through the allegedly self-correcting mechanisms available within the system—are about as far as people are encouraged to reach in pursuit of social change. But the system, which is really a conjoined political, cultural and economic system, is primarily designed to self-preserve, not self-correct. What the system preserves most is the power of the wealthiest persons in the society, who control or strongly influence the politicians by use of lobbyists, bribery and threats to the politicians’ continued luxurious lifestyles or their actual safety. This happens at all levels of government, but is most structurally effective and most firmly established at the federal level. In the United States (and in other nations, as well to somewhat lesser degrees), the “revolving door” phenomenon, in which congresspersons who leave Congress are then hired by corporations to serve as lobbyists to their former colleagues in government, and sometimes later return to politics in higher public offices (such as presidential cabinet positions), is a prime example of this type of political corruption. A 2005 report by the non-profit consumer rights advocacy organization, Public Citizen, found that between 1998 and 2004, 43% of the congresspersons who left their government positions registered to work as lobbyists. Other reports show that another approximately 25% work as lobbyists without officially registering by becoming corporate “consultants” or lawyers.[10] Besides the lobbying aspect of the system—If you need more evidence of the depth of the systems’ corruption and why it will most likely continue to self-preserve for the perpetuation of the mechanisms causing Earth’s biosphere collapse instead of self-correcting to the substantial degree now necessary to prevent such collapse—do some research and analysis on the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 “Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission” decision and on the “pay to play” system which all U.S. congressperson’s (of both political parties) must go through in order to get significant positions on law-writing committees or gain financial support from their party for their next re-election campaign. I could go on and on about the system’s corruption and its likely trajectory, but this is an essay about ideal paths forward and new possible systems, not so much about dystopia. I will only describe enough here about the current dystopian society and its contribution to the global crises to illuminate the need to abandon it and turn towards “utopian” creativity.

While much has been researched and written about the political and economic elements of the conjoined system, not as much has been dealt with regarding the cultural element, which is as much at the heart of the problem as the other two. One study that deals well with that cultural and ethical element, “The Ethics of Lobbying: Organized Interests, Political Power, and the Common Good”, by the Woodstock Theological Center (Georgetown University Press 2002), provides us with a very telling short quote from a corporate lobbyist they interviewed, who chose to speak anonymously: “I know what my client wants; no one knows what the common good is.” For utopian and alternative society thinkers and creators, it is this issue of the common good (which I expand further, below, to include the common well-being of all Life in Earth, not just humans), which the modern industrial political systems seem to have lost sight of, that matters most. If there is still some concern for the common good in modern western societies, the sense of “common good” that seems to prevail is that it is in everybody’s best interest to preserve the established systemic order, keep the money flowing, and continue shopping and consuming way beyond our actual needs. A culture in which personal, individual self-interest, most often manifested in personal material accumulation and consumption as the greatest concern for the vast majority of people, will consequently produce the types of political systems that we are subject to today. If one is familiar with and understands that type of culture, combined with the fact that getting elected to a political office now requires amounts of money that are inaccessible to the vast majority of aspirants to political office, then it should come as no surprise that the vast majority of politicians are more concerned with securing the financial assistance needed to keep their political power than they are with whatever may be the common good.[11]

While it is true that utopian thinking has taken on all sorts of forms over the centuries—from moderately restructured or reformed societies that closely resemble the societies that their creators criticize or reject, to societies that are only different due to the invention and application of phenomenal new technologies or wonders of human innovation, to those societies which are completely, radically different from the status quo systems and culture that their creators have come to reject and refuse to perpetuate—when I think of the type of utopian societies that are needed today, I think of that latter type, not reformism or techno-fixes. I know that pursuing such a path could meet with much opposition and can be dangerous if our opponents ever think that we could actually succeed at creating enough independent, ideal societies to cause the prevailing system to become abandoned and defunct. Suggestions for abolishing and replacing the system with a new way of living that ends the usual limits on the distribution of power and wealth are discouraged, punished (through various social mechanisms, legal and illegal), and sometimes labeled as “treasonous,” a capital offense, which can provide legal justification for a government to end a person’s life. This has long been the case with empires and nation states, whether capitalist or socialist, so why is it so relevant and urgent to risk going in such a direction now? This is a time like no other before it, in which there has never been a greater need for widespread utopian creative thinking and action. If we carefully examine the likelihood of extreme danger for all life on Earth that would result from continuing with the same social, cultural, technological, political and economic systems, according to all of the best available science to date, it becomes clear that we must create and learn to live within some very different types or ways of social life, in order for life on Earth to continue and to minimize the number of extinctions of species that are already set to soon occur, under the present system and its current trajectory. It is a matter of likely consequences and unacceptable risks, like leaving a bunch of matches and highly flammable materials in a room of unmonitored, naturally adventurous little children—but on a much larger, global scale.

Before most people can seriously consider what follows in the rest of this essay, they probably need some more persuasive reasons why such drastic changes to their customary and comfortable “way of life” are necessary. Such reasons can be found within the scientific case for the futility and/or impossibility of successfully resolving the current and near future biosphere crises through current social, political and economic structures or with the use of any actual or imagined technological “fixes.” That case has already been made, increasingly, by numerous experts, in a growing number of scientific reports and publications, so, rather than repeat all of that here, I will just insert some links to some of the best sources for that information for your reference, examination and further evaluation. It is difficult to summarize the essential root of our predicament in just one or two sentences, but as a sort of hint as to what a thorough investigation would find, I will offer you this “nutshell” illustration: capitalist industrial manufacturers seek the most powerful fuel and engines to run their large-scale, earth-moving, industrial equipment as quickly and efficiently as possible, in order to successfully compete, attain or maintain a competitive edge, and maximize their profits. So far, no electric battery powered machinery comes anywhere close to providing the power that they get from fossil fuels. That includes the heavy equipment used to mine and manufacture so-called “green” technologies. The links and a little more information are in the following endnote: [12]

Although having a solid grasp on the latest scientific findings on our predicament is essential to determining our most effective response, many social scientists and psychologists say that the real barrier preventing most people from considering the scientific facts regarding the dire circumstances facing biological life on Earth, and the need for radical societal change, is what people are willing to accept and resign themselves to, instead of making such changes. What are people willing to settle for as “good enough?” That question brings us back to the discussion of how people define “good.” If the type of creative thinking that is now required of us does not mean that we have to come up with something “perfect,” will those who now protest that we utopian creativity advocates are “making the perfect the enemy of the good” switch their accusation to “making the best (or the better) the enemy of the good?” If so, I would still have to ask them, “How do you define ‘good’? How would you define a good society?” Can any society that was built on a foundation of colonialism, slavery, the predatory exploitation of all of the material natural world (including other humans), patriarchy, anthropocentrism, racism, sexism, justified greed, and many other life-destructive perspectives and practices actually become a good society through attempts at reform, especially when the people in power oppose and block nearly all necessary substantial reforms? In the history of the United States, the foundational flaws listed above were not just unfortunate, unintended by-products of a basically just and well-intended government, but, in actuality, the necessary elements for achieving its intended purpose: dominion over all of the human and non-human inhabitants of their illicitly-acquired lands and over any other lands that they might eventually take in the future. Has that fundamental intended purpose of the U.S. (and other human empires) disappeared or ever been relinquished?

One reason why transformational reform towards real justice, equality, and regenerative environmental sustainability is continuously prevented from occurring is that the social mechanisms deemed necessary to perpetuate an empire or large nation-state, including formal education, indoctrination (both religious and secular), economic bondage, and social peer pressure (leveraging the human need to belong), are used by the ruling class in such societies to promote patriotism and widespread belief in the righteousness of the nation’s foundation. It is completely understandable that people want to feel good about their ancestors, their society, and their culture, have a sense of innocence about it all, and not be burdened with a sense of guilt over what the vast majority feel is normal and unquestionable. Such widespread beliefs and comfort zones make it even harder for people to admit that their societies are fundamentally flawed. Even when social beliefs about right and wrong change, over the long span of time, and large numbers of people begin to recognize and assess the errors of their nation’s founders, there remains a need for the ruling class and their loyal subjects to either justify or deny those foundational errors. One of many examples of this practice in the U.S. is the attempt to justify the slaveholding practiced by founders such as Thomas Jefferson and George Washington by referring to them as “simply men of their time,” while denying (or completely unaware of the fact) that 98% of the “men of their time” in the new nation did not hold any of their fellow humans in slavery and the majority of states in the new nation outlawed slavery in their original state constitutions.[14] Another example, used to justify colonialism and the aggressive, often genocidal, separation of Indigenous peoples from their homelands, is the lie that the North American continent was mostly an uninhabited, unused by humans, “virgin wilderness wasteland, ripe for the taking,” at all of the various times and places in which European or Euro-descended people first arrived. For over a century, American academic anthropologists, in service to the ruling class, grossly underestimated the population numbers of Indigenous societies originally in the land now called the U.S., in order to perpetuate that lie.[15] Such institutional social mechanisms stifle and obstruct any imagined or actual significant correctional mechanisms that people believe are built into the system. People who have been effectively taught that their societal system is designed to repair its own flaws (no matter how foundational or essential those “flaws” and outright atrocities are to its existence) through its authorized “proper channels,” that such processes for correction must take lengthy amounts of time (perhaps even generations, for major flaws), and that creating new societies built on better foundations is unnecessary, impossible, and maybe even “treasonous,” tend to accept the common assumption that their society is either “good,” “better than other countries,” or, at least something we can call a “lesser evil.” We have also been effectively conditioned to accept lesser evils in nearly every political election campaign, especially at the national level, and every time that we must transport ourselves somewhere that is too far away to walk or bike to, even when we would prefer not to use fossil fuels or toxically-mined and produced lithium at all. Is a “lesser evil” the same thing as “good?”

Is a society that is so destructive to life that the best rating that it could give itself on environmental sustainability is “lesser evil” actually a dystopia?

Unfortunately, it seems that most subject peoples of modern industrial nations have come to define “good” and “lesser evil” as basically the same thing. Maybe the two-word phrase that most people would use to define the state of our current societies and our assumed-as-necessary daily compromises with evil is “good enough.” To that statement of submissive resignation I just have to ask, “good enough for what?” Good enough to keep a sufficient roof over your head and food on your table, at least for this month? Good enough to put enough gas in your tank so that you can continue to drive to that job of yours that just barely pays you a “living wage?” For those who have been a little more fortunate, a little more submissive, compromising, and “well-adjusted”—and, therefore, better-rewarded—does “good enough” mean “at least I get to have all of these great toys and continue to consume way beyond what I really need?” Good enough to keep you binging and streaming your life away? To those who do not define a “good enough” society based solely on its material benefits to themselves, and think more about the well-being of all members of the society (or, what used to be called the “common weal,” or, “common good”), does a society where 5% of its members own 67% of the wealth have a “good enough” economic system?[16] Is a society that is continuously engaged in illegal wars fought only for the purpose of generating financial profits for the owners of various industries “good enough?” Is a society of human beings whose minds are so twisted by the colonialist concept called “race” that they actually have no idea what a human being really is “good enough?” For those who care about preserving Earth’s natural systems that keep us alive, is a society in which the majority of its citizens are so out of touch with and alienated from the natural world that they do not realize that they need those interconnected natural systems (much more than they “need” money) in order to remain alive “good enough?” When confronted with the painful and repulsive fact that their society’s way of life is actually destroying life on Earth and bringing many species, including their own, rapidly towards extinction, some people reply, in attempted self-defense, that there are other nations which are doing more harm to the natural world than their own country is. Is a society that is so destructive to life that the best rating that it could give itself on environmental sustainability is “lesser evil” actually a dystopia? I think that any society that destroys their natural source of biological life simply by carrying out their normal processes of living, within the laws, customs, and ordered structures or systems of that society, and cannot bring themselves to stop doing so, is a dystopian society. Is living in a dystopian society “good enough?” But, again, let’s not get bogged down with endless examples of social dystopia. The only reason I am writing about dystopia here is to point out the need to move towards new (and some old) utopian, or actually ideal, ways of living. So, let’s proceed now in that direction.

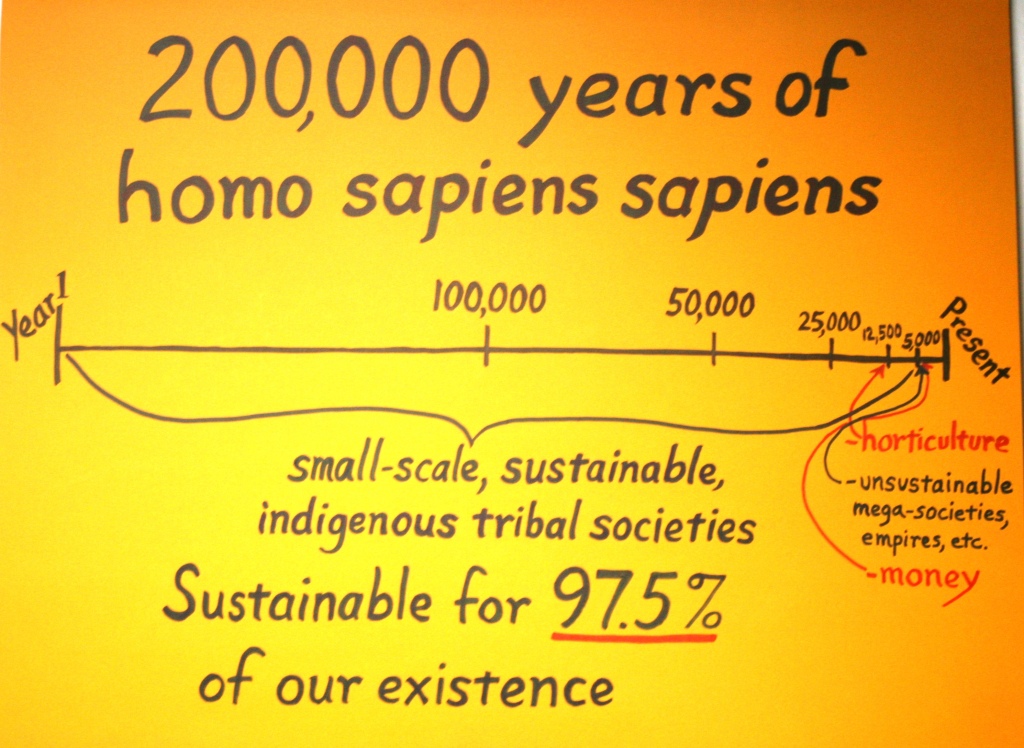

What really is the “normal” way of human life in Earth, over the broad span of human history? The reason that I inserted the image above is to give everybody a sense of what is possible for the human species on this planet, and to de-normalize the ways we have been living for the last 5 to 7 thousand years, or 2.5% of our existence.[17] Before we began to go the wrong way, disrespecting and exceeding the carrying capacity of our ancient ancestral homelands (and/or other people’s homelands, taken through conquest or colonialism), all of our various Indigenous ancestors[18] practiced ways of life that were guided by local ecosystems and all of our interconnected and related fellow living beings. Those were harmonious, regenerative, sustainable, and (though not “perfect”) probably mostly joyful, peaceful, thankful and abundant ways of life.[19] We are still that same species and this is still the same planet, even when we take into account all that has changed, and all the vital knowledge that most of our people lost long ago. We will not know what is possible, regarding a return to at least some aspects of the old normal, until we make our best attempts to do so.

The points in time at which various ancient human societies began to go the wrong way (whether by force from outsiders, or by bad decisions made from within) are numerous and span thousands of years, but, thankfully for our future, some few remotely-situated Indigenous societies around the world never departed from those basic, ancient ways of seeing and living with the natural world and still have enough of their ancestral homelands not yet confiscated or destroyed by colonialist predators to make that continuance possible. The Kogi people of the northern Andes mountains in Colombia are a prime and now well-known example,[20] as are some of the more remote tribes to the south and east of them in the Amazon rainforest. Other relatively intact traditional indigenous societies exist in remote locations in central Africa, the Pacific islands, northern and southeastern Asia, and a few other remote locations in the Americas and elsewhere.[21] It is by learning from people such as these, and from all of our relations in the non-human world as well, that we might be able to find our way back to truly green, sustainable and regenerative ways of life. There are also many more Indigenous peoples throughout the world who have just a little or none of their ancestral homelands still accessible to them, retain only pieces of their traditional cultural values and practices, and have just a small number of tribal members who are still fluent in their ancestral languages. Colonialism, capitalism, cultural oppression, and intercultural relations have brought many changes to them, but, even so, for people whose encounter with wrong ways of living is more recent than most of the rest of humanity, the way back to truly green eco-harmony might be a little easier.[22]

Unless a community consciously agrees to put the needs of their entire local ecosystem and all lives within it first, above what they conceive to be human needs, their community will someday fail and collapse.

As clearly as we now see that the concept of utopian societies was never meant to mean “perfect” societies, it should also be clearly understood that traditional Indigenous societies were never perfect either, just as no human society has ever been perfect and none ever will. But, model ideal societies do not have to be perfect to provide inspiration, wisdom, and direction for our paths forward into the difficult future. It is interesting to note that the first contacts that European colonialists and their descendants had with Indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere (or, “the Americas” and the first people to be called “Americans”) inspired a small wave of utopian thinking that lasted for centuries,[23] and now, in this time of profound global crises, many people are looking to Indigenous individuals, societies and cultures for guidance and leadership towards resolution of the current crises and for ways to create viable, Earth-sustaining and regenerative future communities. Many utopian community social experiments have come and gone over the last five centuries, and one reason why the vast majority of them failed is that they did not look closely enough at the models to be found in Indigenous societies all over the world. While some communities have mimicked Indigenous, eco-based, reciprocal economic models to some extent, and others have imitated Indigenous representative political models, there are two elements of the original ways of human social organization, which nearly all non-Indigenous-led utopian communal experiments have missed, and which are essential to ideal community success. One element is the understanding that humans are just one of millions of types of people (or, “species”) who all have the potential to make essential, invaluable contributions to the interconnected web of regenerative life on Earth.[24] All species of the living world belong here and need each other. People from anthropocentric, “human needs first,” or “humans-are-most-important,” or “humans are superior to all other species” societies have an extremely difficult time trying to see that, unless they somehow acquire a special ability to break free from that very powerful mass delusion. Unless a community consciously agrees to put the needs of their entire local ecosystem and all lives within it first, above what they conceive to be human needs, their community will someday fail and collapse. A big step on the way to getting there is to realize that the greatest human need is to be in tune with the needs of the entire living organism to which we are all connected.

The second element is the need to learn how to have deep communion or interactive communication (listening, hearing, and being heard) with all of our non-human relations in the natural world (animals, plants, earth, water, fire and air). That idea sounds very unreal, or even impossible, to most modern humans today, but there are many stories and indications that most of our species once had and commonly engaged in such abilities, throughout most of our history as homo sapiens sapiens. Although I probably will not be able to recover much of our former fluency in such communion, after 70 years of living in this corrupt, lost, degenerated modern industrial world, I will remain committed to working on that quest for all of the remaining time that I have to live in this body, with all of the species by which I am surrounded. Why? Because I expect that we can learn more about what Mother Earth wants from us and how we can be healed and corrected, from our innocent, already-connected, harmonious, right-living, non-human relatives than we can from just listening to and following other humans. Daniel Wildcat (Yuchi, Muskogee), professor of American Indian Studies at Haskell University, helped to clarify this Indigenous perspective in his ground-breaking 2009 book, Red Alert: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge:

Current scientific research on animal communication overwhelmingly verifies the existence of complex communication systems. Honesty and humility require us to acknowledge that indigenous knowledge, in its diverse substance and structure, is the result of collaboration, a respectful partnership, between us and our many other-than-human relatives. Several tribal elders I have known have been almost matter-of-fact about their ability to exercise interspecies communication with animals.[25]

The old ability to also commune with and hear the languages of the plant beings is eloquently described by Potawatomi scholar and award-winning nature writer, Robin Wall Kimmerer in a recent essay that was re-published in Yes! magazine:

The Indigenous story tradition speaks of a past in which all beings spoke the same language and life lessons flowed among species. But we have forgotten—or been made to forget—how to listen so that all we hear is sound, emptied of its meaning. The soft sibilance of pine needles in the wind is an acoustic signature of pines. But this well-known “whispering of pines” is just a sound, it is not their voice….Traditional cultures who sit beneath the white pines recognize that human people are only one manifestation of intelligence in the living world. Other beings, from Otters to Ash trees, are understood as persons, possessed of their own gifts, responsibilities, and intentions. This is not some kind of mistaken anthropomorphism….Trees are not misconstrued as leaf-wearing humans but respected as unique, sovereign beings equal to or exceeding the power of humans.[26]

We definitely won’t get to successful, regenerative, natural Life-connected communities just from reading books written by other humans. This is not a simple philosophical exercise or an intellectual parlor game. We have to actually live the interconnected life, under natural laws and the wise limits of Mother Earth, on a finite but abundantly sufficient planet. That was the old normal way of living for the vast majority of our species, for the overwhelming majority of the time of our existence in Earth.

Some other essential elements for successful utopian societies at this particular moment in global history, besides the two most important elements mentioned above, include:

- A group of people with a common enough vision or sense of direction, not excessive in population for the particular place in which they live so that they do not overshoot the carrying capacity of their local ecosystem or need to trade with the world outside their community for material goods[27], and can help to maintain regenerative processes and relationships between all species of life in that local ecosystem/community. Eventually, the community would need to determine their own membership or citizenship requirements and limits.

- Access to sufficient land and clean water. This might require that people pool their financial resources and purchase land together. A more remote rural location would be safer, but for people who feel that they must remain living in urban locations, at least for the short-term future, city or town governments sometimes lease vacant lots relatively cheap for use as community gardens. When looking for land to build community upon, I think that it would be best to leave the more pristine, wild, intact old ecosystems alone and instead look for one of the many places that have already been damaged to some extent by human activity. Earth needs us to help heal and regenerate such places and I feel that we are obligated to do so, as a way of paying Mother Earth back for all of the generous gifts of life that our species has wasted and destroyed, as well as for those gifts which were rightly used. That is what we have done on the five acres that we have lived upon for the last thirty-seven years. It was in pretty rough, damaged condition when we first moved here and since then we have assisted our non-human relatives in re-establishing their interconnected communities, buy bringing in water, trees, and fertile soil and simply letting life live.

- Sufficient collective knowledge and experience within the community membership about how to care for and nurture a wide variety of edible plants, either native to the place where the community lives or compatible with that ecosystem, to organically grow or gather for food and medicine. Knowledge in sustainable, respectful hunting and fishing might also be useful or necessary.

- A commitment by all community members to expanding the community’s collective knowledge of the lifeways and connections between all species in the community’s ecosystem and learning how humans best fit into the interconnected purposes of life in that place. Knowledge of the lifeways of the people who were, or still are, indigenous to that place is an essential part of this process. As much as it may be possible, that knowledge should come directly from the people who are indigenous to the community’s place, whenever and how much they may be willing to share that knowledge, and such people should be invited into those communities and have leadership roles there, if they choose to do so. Generally, though, most Indigenous peoples would prefer to form their own ideal communities on their own ancestral lands or reservations.

- Although ideal or utopian communities may need to use some money to get the community started, ideal communal economies should eventually become moneyless, direct-from-and-back-to-nature (ecologically reciprocal), mutually reciprocal, life-giving and sharing societies. In the formerly normal pre-monetary world, a society’s wealth was received directly from relationship with the natural world and was preserved or enhanced by maintaining a good, respectful, reciprocal relationship with the natural world. If our economic dependency is on the well-being of local natural systems, that is what we take care of and if our dependency is upon money, then that is what we care about most. In old Indigenous societies, the honorable attitude was to look out for the well-being of all people (human and non-human) in the community, give generously without worrying about what you will receive in return, and NOT measure out individual material possessions mathematically, to assure exactly equal portions of everything to each individual. In a culturally generous gifting economy, sometimes individuals or families would be honored in a ceremony and receive many gifts from the community, making them temporarily rich in material possessions. On another occasion a family or individual might sponsor a feast for the whole community and give gifts to all who attended until they had no more possessions left to give. When such activities were frequent and commonplace and people knew that they were connected to a generous, caring, cooperative, reciprocating community, of both human and non-human beings, there was no anxiety or sense of loss about giving one’s possessions away. Generosity was such a highly-esteemed, honorable character trait, that people sometimes actually competed with each other to become the most generous. There was also social shaming attached to being stingy or greedy, which is seen in some of the old stories, along with the stories about generosity and other positive traits.[28]

- The community would need to mutually agree upon a governing structure and decision-making processes for issues that involve or impact the entire community (including the ecosystem and non-human members of the community). Community rules and laws should conform to and not violate nature’s laws. Effective government depends on mutual respect and/or love, listening and communication skills, common core vision and goals, honesty, transparency, and a commitment by all community members to working on and continually improving their self-governing skills.

- Democratic or consensus decision-making about what technologies and tools will be allowed in the community, again giving highest regard to what would be best for the entire ecological community and for the connected biosphere of our whole planet.

Here again are the first two necessary elements of ideal community creation (explained above, before this list), reduced to nutshell, outline form:

- Relinquish all anthropocentrism and any concepts of human superiority over all of the other species that we share interconnected life with in our ecosystems and in the entire biosphere of Mother Earth. Recognize the interconnected value of all species of life and keep that recognition at the forefront of all community decision making. (How can the species that is the most destructive to Life on Earth be rightfully considered “superior” to any other species, much less to all of them?)

- All individuals in the community should commit themselves to actively developing our formerly common human abilities to commune deeply with and communicate (listening, hearing, and being heard) with other species in our inter-connected natural world. Since, for many of us, our ancestors lost those abilities hundreds or even thousands of years ago, a community should make no requirements about the speed at which those abilities should be developed. It should not be a contest, but, instead, a mutually-encouraging, enjoyable, natural process. With each successful step that any individual makes in this endeavor, the entire community gains greater ability to more closely follow nature’s laws and gains a better sense of how humans were meant to participate in and contribute to Earth’s living systems.

There are probably many more essential elements of community formation, structure, and actual operation which people may feel they need to consider and discuss. The reason that I titled this essay “Paths (plural) Forward….” was to acknowledge that there will be innumerable forms that ideal communities will take, throughout the world, depending upon the needs of local ecosystems and all of their inhabitants, the will of the particular communities, their sense of the common good, and whatever creative ideas that they come up with.

Some Obstacles and Possible Scenarios on the Near Future Paths Forward, both Good and Bad:

The idea of giving up and abandoning modern technologies is unthinkable and even abhorrent to most present-day humans. Besides those humans who have an abundance or excess of such things, many people around the world who own very few modern technology products are also repulsed by the idea that they might have to give up even the dream or desire to have such things. To abruptly switch to pre-20th century, or earlier, technologies would be excruciatingly painful to most modern, western industrialized people, and even a slow transition would be quite hard. It is possible that, to somewhat ease the transition to truly green and bio-sustainable living, we could just end the production of toxic modern technological products, while still using those things that already exist until they’re spent or broken and then not replace them (but cease immediately from using items that burn fossil fuels or emit other toxic wastes, in their production or consumption). Some items could possibly be re-constructed from discarded parts, until such things are no longer available. During the time span in which the old manufactured goods are being used up, people would simultaneously need to be very actively engaged with learning to bio-sustainably produce the things that they actually need and that are actually green or Earth system friendly. That might be, at least in part, what a viable transition could look like. Obviously, most people today would absolutely reject and resist such a change, due partly to not knowing any other way to live, alienation from nature, fear of the unknown, and belief in, addiction to, or imprisonment by their normal material culture. Just wrapping their minds around the realization that so many things that they had always considered to be normal and innocent should probably never have been made, will be nearly inconceivable to most, at least initially. I remember how hard it hit me when I first realized that we just cannot continue to go forward with the status quo social systems and most of their by-products and still have a living world for very long. But how many will give it a second thought or change their minds after personally experiencing the increasingly common excruciating pain of global warming natural disasters? At some very near future point, relief agencies, all of which have finite resources, will not be able to keep up with the increasingly frequent catastrophic events, including more pandemics (connected to thawing permafrost, increased trade and travel, and increasing displacements and migrations of humans and other species). Is the creation of ideal or “utopian” local eco-communities, immediately and proactively—like building the lifeboats before the ship actually sinks—the best possible and most viable path forward, both for humanity and the rest of Life on Earth?

Because of the likelihood that modern industrial humans will not respond quickly or adequately enough to sufficiently (or even significantly) alter our present global destruction trajectory, the creation of utopian eco-communities might become more of a post-collapse source for places of refuge or survival and healing for those relative few who do manage to survive, than a means for actually providing an appealing alternative to continuing with the status quo, or just limiting the harm caused by our predicament. It may be likely that even those of us who would like to create utopian eco-communities would have a hard time doing so as long as the option of continuing with the status quo still exists, because we are so conditioned to depend on or desire many of the things that society offers us. Either way, though—whether prior to the collapse of the status quo or after—the creation of such communities would be a good thing and probably the least futile use of our time, attention and energy.

I offer here a brief assortment of some possible near-future scenarios, both positive and negative:

1. Sometime within the next five years, about 60% of humans around the world decide to create local eco-utopian communities, following the old Indigenous principles described above, and begin the process of abandoning modern industrial technological social systems and structures. Soon after that, we also begin the difficult process of safely de-commissioning all of the existing nuclear power and nuclear weapons facilities in the world and sealing away the radioactive materials therein. The bio-system collapse already set in motion to that point continues, but at a rapidly diminishing rate, as Earth’s regenerating systems are allowed to take over and bring gradual healing and an opportunity for a new direction for humanity, rather than repeating our former disastrous mistakes. As the human people begin to experience the joy of re-discovering our real purpose as part of Earth’s interconnected life-regenerating systems, while simultaneously grieving about all of the increased suffering of the humans who are still stuck in the collapsing, chaotic old industrial societies, and offering refuge to any persons that their communities can take in, many ask each other the question, “why didn’t we start doing this much sooner?”[29]

2. In the initial first few years of the international, local utopian eco-community movement, very few people take it seriously and the vast majority of humanity knows nothing about it. Government security agencies in the wealthiest nations of the world know about it, but only because they spy on everybody, and not because they see the movement as a serious threat, as they assume it would never catch on due to the common unquestioning submission to the system and consumer addictions to modern technology and over-consumption. During those same first few years, the corporate-controlled wealthiest governments are much more concerned with the growing far right wing revolutionary movements in the U.S. and much of Europe than they are with the mild-mannered, willing to work through the system, so-called “left.” The fringe right, or the tail that wags the Republican Party dog, successfully breaks Donald Trump out of prison, and re-elects him as President in 2024, then designates him to be “President-for-life.” Though at one time useful tools for the ruling class’s divide and conquer strategy, at this point the rulers determine that they have become somewhat unmanageable, since an obvious one party state is not as useful or dependable as two parties masquerading as opposites, when they actually serve the same corporate economic masters. So, the corporate rulers decide to make the far right wingers of the U.S. an example to the far right in Europe and to any on the far left in the U.S. who might be encouraged to try something similar with the harder to wag Democratic Party dog. The U.S. military is called in, they stage a coup against Trump and his cohorts, and begin mass imprisonments, and some executions, of many of the remaining right wing revolutionaries (except for the ones who cooperate with the government, making deals and submissions in order to save their “me first” lives). It is only after that that the governments of the wealthy nations of the world and their corporate handlers begin to notice that the utopian community movement had grown exponentially during the years that they were pre-occupied with the far right. Of course they had noticed that consumer spending had diminished considerably throughout the “developed world,” but had attributed that to other usual economic factors and to the extensive hardships caused by the increasing natural disasters, including the most recent pandemics. Once they realize that the eco-utopian movement has the potential to completely bring down the prevailing economic system, they get right on it. One useful tactic they find for dealing with the situation is to employ the now scattered, frustrated, scorned, unemployable, and even more fearful far righters as mercenary soldiers against the eco-utopians, whom they easily scapegoat for the deteriation of the economy, with very little need for indoctrination. Most of the righters agree to serve just because of the promise made to them that they would get their guns back after they complete their service to the country. Simultaneously, the EU, Russia, China and other governments use their more conventional militaries and other methods of persuasion and suppression to deal with the situation.

3. Instead of rejecting modern industrial technological society altogether, the majority decides to try technological “fixes” to our predicament instead. They generally agree that saving the capitalist system, their precious, hard-fought-for careers, and their even more precious levels of material consumption are more important than saving biological life on Earth itself. But, in order to save capitalism and the status quo civilization, and avoid an international socialist revolution, they realize that some more significant and more convincing gestures need to be made toward CO2 reduction. In 2023, production and installation of solar electricity panels and wind farms begins to increase rapidly throughout the world, along with all of the toxic, CO2-producing mining, manufacturing, construction, deforesting and defoliating of natural habitats for new power lines as well as for the new power installations themselves, road-building, hauling of equipment, workers, and the products themselves to retailers and installation sites, and more—all of which involve a huge increase in the burning of fossil fuels. Even though the alleged purpose for all of that increased industrial activity would be to replace fossil fuels with “green energy technologies” at the scale needed to keep the precious system going and growing and create more jobs, the unexpected or oft-denied negative consequences soon become nearly undeniable (but humans have the ability to deny just about anything—or, actually, just anything). The oil, lithium, and “green energy” companies then use their greatly increased profits for advertising and indoctrinating people to trust the new “green” uses for fossil fuels. They also use some of the new profits to purchase the cooperation of additional politicians and entire governments in protecting their enterprises. The bio-system collapse, natural disaster and mass extinction trajectory then continues, at a more rapid rate.

4. By 2033, it becomes widely obvious to the majority of humans that the “green” energy techno-fix for the continuation and growth of modern industrial capitalism is not really that green and is actually exacerbating global warming and the continually increasing environmental catastrophes, while pulling attention and resources away from both the urgently-needed disaster relief and the struggle against the seemingly endless parade of new pandemic diseases. Because they still have not developed any proven technologies or machinery for sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere at anywhere near the rate needed to get back to the 2° C “point of no return,” which we had already passed back in 2028, the ruling class then decides to proceed with the next great, unproven, theoretical techno-fix: injecting sulfides and/or other chemicals into Earth’s only, increasingly fragile, atmosphere in an attempt to block or reduce much of Father Sun’s gift of radiant light and warmth—a technology called “geoengineering,” or artificially forced Earth cooling. Very soon after the first widespread use of that techno-fix, we then get a “Snowpiercer” scenario, but without the horrific, impossible, perpetual-motion prison train “lifeboat.” We just get the entire planet frozen to death.

5. The complete collapse of the modern industrial economy occurs in the year 2029, due to multiple factors (too many to list here, but they include some of those listed in the scenarios above and many things that are actually happening RIGHT NOW). The radical left finally realizes then that a real opportunity for a successful socialist revolution is now upon them, effectively dropped right into their laps. They can actually just vote it right in, throughout the so-called “developed world.” Seeing the writing on the wall, the trillionaires and billionaires decide that the whole planet has become unmanageable and too out of control, so they make one last plundering of the planet’s gifts (a.k.a., “resources”) to build up their private spaceship fleets and build more space stations, in preparation for their last grand exit. Many of the millionaires and wannabe trillionaires do whatever they can to join them and those who fail to make the escape then also fail at a last ditch attempt to save capitalism. Many eco-utopians and eco-socialists advise the more conventional Marxist socialists that socialism will fail without putting the needs of the natural world first (instead of just the humans) and doing away with money. After much productive discussion around the world, in-person and by the internet (whenever the intermittent grid is up and running) it is generally agreed that nation states and empires have run their course, done much more net harm to life in Earth and the common good of humans than their assumed “benefits” can make up for, so the human people decide to abolish all such political entities. They also decide that, instead of nations, human societies should be small, local, eco-centered, non-monetary and truly democratic, while staying in touch with each other through communication networks, with or without the electric grid. For several decades after that glorious beginning, as the Earth begins to heal through natural regenerative processes and the humans begin to discover who they really are and how they fit within the Whole of Life, they also discuss whether or not they should continue to use electricity, and, if so, what limits upon such use does Mother Earth and all our non-human relations recommend to us?

6. OK, just one more possible near-future scenario to give here, although I am sure that we all could think of many more. Nuclear war breaks out between the U.S. and China in 2022, with additional participation from Russia, the EU, and North Korea. China targets both the Yellowstone caldera and the San Andreas fault. We get combined nuclear and volcanic winter, and the Earth freezes to death. A couple of the trillionaires, with their entourages, manage last minute, rushed, and not completely prepared, spaceship exits, and end up starving to death in outer space within a couple of years (having extended the time of their survival with cannibalism, of course).

Which of the above scenarios seems most likely to occur, in your opinion? Do you think that something else would be more likely and, if so, what? What would you like to see happen? Do you feel free to think with utopian creativity? If not, do you understand why that is? Would you like to have that freedom and engage in such creativity for the common good?

I realize that, for many of you, this may be the first time that you have heard of many of these dismal realities regarding the present condition and future prospects of life on Earth. As I began to say earlier, I have not forgotten the dismay, anger and other emotions that I felt when I first became aware of some of these facts (and other facts that I did not go into here), several years ago. There are many other people, around the world, who are going through the same thing and there are support groups and other resources that have been formed over the years to help people get through this together and peacefully adapt to it.[30] For me, the way I deal with it best is to try to create alternative, natural living paths forward. Just because the status quo way of societal life is doomed does not necessarily mean that all life or all potential human societies are doomed.

I also realize that for many of you this may be the first time that anybody ever told you that utopian does not really mean “perfect” or impossible, and that exercising our utopian creativity might be not only a good thing, but an absolutely essential thing to do at this particular time. It might also be the case that you have never heard that traditional Indigenous societies and lifeways might provide us with models for viable, Life-saving, Earth-protecting, regenerative paths forward at this time, instead of being the “miserable,” “brutal,” “struggles for existence” that you might have heard about in some anthropology class. The future might indeed look like it is going to be a painful struggle for life, for both humans and non-humans, but engaging in survival efforts as communities with united visions, a common sense of purpose, shared resources, shared abilities, seeking the common good for each other and for all species of life in our local community worlds, will be much easier and more enjoyable than trying to pursue mere survival as “rugged individuals” or rugged little nuclear family units. Embarking upon these paths forward to “utopian,” ideal, or best possible and ever-improving human eco-communities might be what our Mother Earth and all of our relations of all inter-connected Life have been yearning for us to do for thousands of years! I am excited to find out what we will learn in the actual doings.[31]

[1] Beck, Peggy V., and Anna Lee Walters, The Sacred: Ways of Knowledge, Sources of Life, Navajo Community College Press, Tsaile, Arizona, 1992. Clark, Ella E., Indian Legends From the Northern Rockies, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 1966, 1977.

[2] The recent COP 26 debacle, which intentionally excluded participation by many Indigenous and other heavily-impacted peoples from the global south, and the infrastructure bill passed by the U.S. Congress that same week provided us with fresh examples of that futility, which many of us have long realized is the case.

[3] To be clear and fair, the word, “perfect,” in 16th century English, usually meant “complete” or “absolute,” although in certain contexts could be interpreted as “flawless” or something more like the way we define “perfect” today.

[4] Raphael Hythlodaye, Thomas More’s fictional friend who tells the story of his time in Utopia, is said to have gone there with Amerigo (a.k.a., “Alberico”) Vespucci. More’s Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson, printed from the second edition, 1556, page viii.

[5] Utopia, pp. 164 and 165.

[6] As you may already know, More did eventually serve Henry VIII as a counselor, until Henry had him beheaded for refusing to publicly agree with him on the topic of divorce and remarriage.

[7] See, Anitra Nelson and Frans Timmerman, eds., Life Without Money: Building Fair and Sustainable Economies, London, Pluto Press, 2011.

[8] More’s Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson, printed from the second edition, 1556, page 171. One of the minor characters in the book writes a poem speaking on behalf of the nation of Utopia personified, saying, “Wherfore not Utopie, but rather rightely my name is Eutopie, a place of felicitie.”

[9] Beginning with the radio.

[10] Thomas B. Edsall. “The Trouble With That Revolving Door”, New York Times, December 18, 2011. That and 176 other reference citations, along with an extensive list of “further readings” on the topic, can be found in the excellent Wikipedia entry, “Lobbying in the United States,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobbying_in_the_United_States

[11] Perhaps the only way that the politicians of today would prioritize the needs of the people whom they allegedly represent, over the will of the corporations who lobby them, would be if the people could form their own “Lobby for the Common Good” and that lobby was funded well enough to surpass the enormous dollar amounts in bribery of all of the corporate lobbyists combined. But, increased corruption of the electoral process (gerrymandering, artificially-constructed “gridlock” through the invincible two-party system, “divide and conquer,” etc.) is also making the people’s voice and will less relevant to the concerns of politicians.