This is a revised version of a long ago post, formerly titled, “The Problem With Money,” and it now includes a “Part 2” on actual alternatives to money-based economic systems (now in place and being practiced), as well as some others which may be possible. I hope that these additions to this essay will give people a better sense of what really is possible regarding Earth-friendly, sustainable, systemic change. If the description in Part 1 of our current crisis and its origins becomes too disturbing for you, I recommend skipping ahead to Part 2 and finding some relief in the descriptions of positive alternatives for really living in sustainable, life-affirming societies. But Part 1 explains why we really need to go to and create the types of societies described in part 2.

This is my final revision (2-1-2019) of this essay. Until we come up with a better plan for avoiding extinction and/or replacing the life destroying social and economic systems, this will be pretty much all that I can propose. Now I can just go back to writing about what we are actually doing–on our farm, other farms, and in our local communities–to create the truly eco-sustainable alternatives that life on Earth needs. I look forward to interacting further with other, like-minded activists, as well as anybody who just has questions and thoughts about this topic, and responding to your comments, questions and ideas. I also left the older version on the blog (item #2 on the linked Table of Contents in the menu bar, or just click here) to preserve the conversation that followed it. I hope that this one generates even more conversation and, better yet, some positive, revolutionary action.

Photo illustration of dirty money in the Tribune Studio on Wednesday, 11 Jan 2012 for the features section. (Bill Hogan/ Chicago Tribune)

The End of Money: The Need for Alternative, Sustainable, Non-monetary Economies

Part 1: What Is the Problem?

A passage from a very popular book says, “The love of money is the root of all evil.” Now and then, we hear somebody misquote that passage, or accurately quote somebody else who misquoted it, saying, “Money is the root of all evil.” In my not-so-wise, or more-naïve-than-I-am-today, younger years, I would sometimes rush to correct the misquoters and tell them, somewhat self-righteously, “It is not money itself, but the love of money that is the problem. Money is a value-neutral object and can become positive or negative depending on how we use it.” Maybe so or maybe not, but in recent years I am thinking more and more, not. Of course, if there was no money, if we had an economy in which we did not use currency, then nobody could fall in love (or lust) with it. That is not a complete or seamless argument for doing away with money, and I don’t think that anybody can logically argue that if there was no money there would be no greed, or no evil at all. Even so, when we consider all of the harm that has come to humanity, other species, and the planet itself due to the amoral, predatory and sometimes horrific practices that have spawned from the pursuit of money, along with the possibility that even the more humane uses of currency enable the destructive uses, it might be a good idea at this time of seemingly imminent peril for all life on Earth to at least seriously contemplate some non-monetary ways of engaging in economic life.

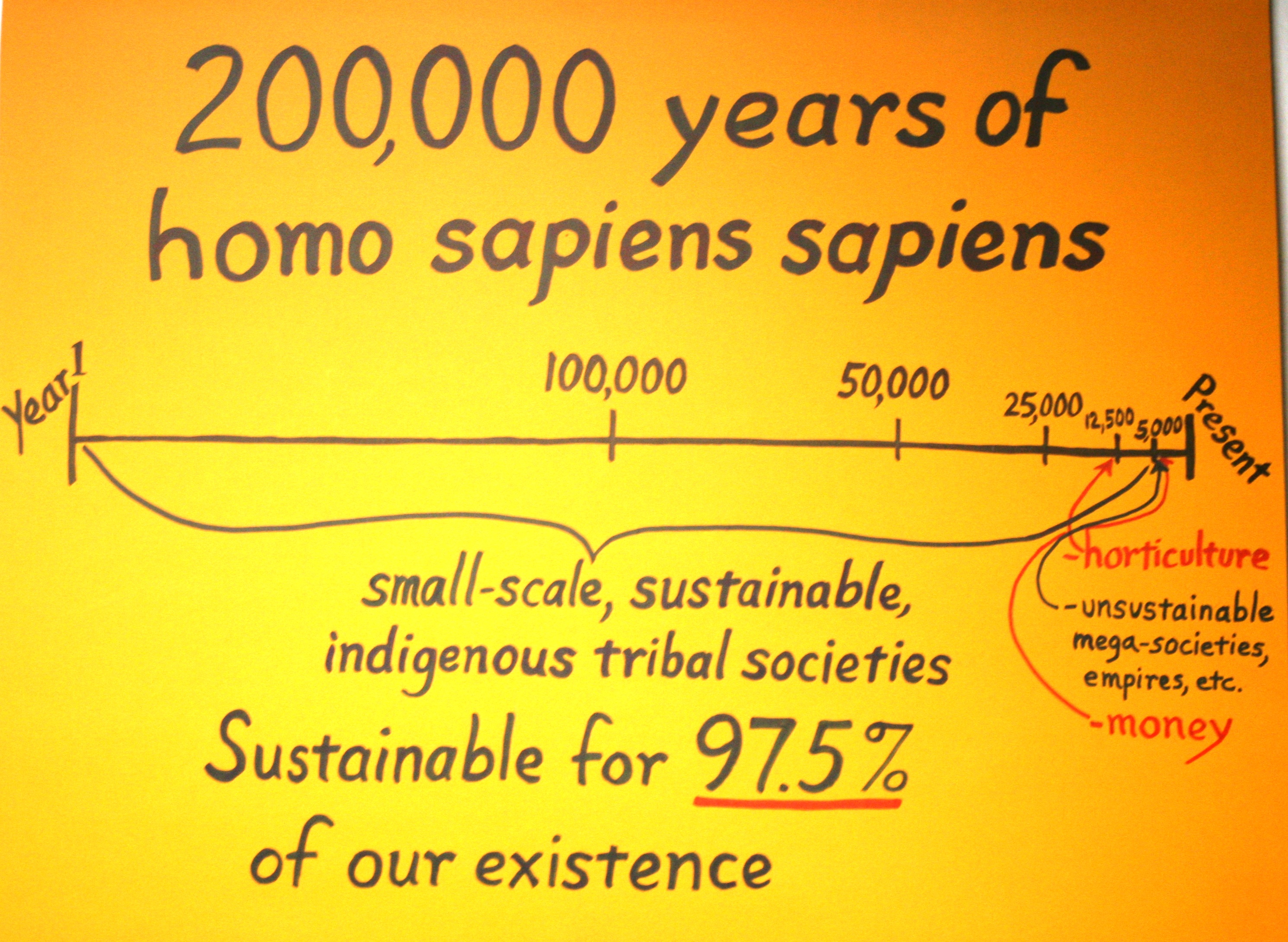

What is the point of discussing the idea of a world, or even a small local economy, without money, especially when most humans today cannot even imagine such a world and consider the use of currency to be one of the most inescapable, inevitable realities in all of existence? Even though it seems to most people that money “has always been with us,” the fact is that money has only been a part of the world of homo sapiens sapiens for about 2.5% of our existence (about 5,000 out of 200,000 years).[1] Our species has always had economic practices, or ways of acquiring and utilizing the material goods that we need for life, but for 97.5% of our existence as a social species we have done so through direct, sustainable interactions with the natural world, without the need for using currencies. The advent of exchange currencies was a result of scarcity caused by societies becoming unsustainable to their homeland bases, through overpopulation and/or over-harvesting, thus losing their economic independence, and therefore becoming compelled to depend on trade with other societies. Before arriving at that crucial point, some human societies occasionally engaged in trade for natural resources and/or human-crafted products, but more out of desire than actual necessity. They desired to enhance an already abundant, or, in lean times, at least sufficient way of life with the luxury of a little more variety, while simultaneously meeting the need to maintain harmonious, stable relations with neighboring tribal societies. The economic focus of those ancient societies was to maintain the balanced, reciprocal, life-sustaining relationships between human communities and their natural world or local ecosystems. If their populations became too large, or unsustainable for the carrying capacity of their homelands, tribal societies would split and move part of their society to another location far enough away to maintain sustainability, while still being close enough to maintain contact and interaction with their relatives.[2] The failure of some tribal societies to split and relocate (after attempts to maintain sustainable population levels had also failed) was probably the primary reason for the initial human forays into unsustainability, dependence on trade and the aggressive practices of empire-building. When trade became a necessity for survival, rather than a take-it-or-leave-it luxury, monetary systems soon followed, and many human societies eventually became more attached to and enamored with money than with the real source of life and well-being that we had always known before: the natural world itself.

The advent of unsustainable mega-societies and empires is at the root of most of the severe problems and horrendous circumstances that we humans and all other species of life are dealing with today. As the early mega-societies departed from their prior indigenous ways of living, which were based in respectful reciprocity with the natural world, and moved into a disrespectful mode of seeking to dominate and control nature, including other humans, as well as all other species, “wealth” (well-being) became increasingly associated with both currency and dominant physical force. This departure from their ancient indigenous spiritual and physical traditions required them to devise ideological and religious justifications for this major change. From that dilemma arose patriarchal, violent god-figures and religions to replace their traditional earth-centered, matriarchal, nurturing, Earth Mother-centered indigenous beliefs and practices. Consequently, the status and roles of women were diminished in such societies and leadership roles became the almost exclusive domain of males with sufficient wealth and force to command authority.[3] Empire after empire reinforced that norm, although occasionally the daughter of a patriarch emperor or king was allowed to rule, usually for lack of any suitable male offspring to take the patriarch’s place. From unsustainable empires sprang not only sexism and misogyny, but also colonialism, slavery, ethnocentrism, racism, religious exclusionism, anthrocentrism, the commodification of nature, capitalism and numerous other means and justifications for the ruthless exploitation and oppression of every type of “other” (other than self) in the natural world. The power to treat the world that way has always been reinforced and facilitated by the accumulation of money and militaries, which also increases the pressure to create more powerful weapons and pursue unlimited increase in one’s own supply of such objects.

After colonialism and empire-building crossed the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the level of ruthless, predatory competition increased exponentially, creating a rapid increase in the rate of so-called technological “advances” that could provide a competitive edge in the practice of pillaging and plundering, leading to modern industrial capitalism by the early 19th century, coinciding with the rise in CO2 levels and numerous other deep wounds and permanent scars on Earth and Water. As all of these processes continued, and their negative impacts were normalized and accepted by the masses of citizens, world-wide, another major obstacle to progressive change was also created: many people became too alienated and insulated from Nature to recognize her as their Source of Life, that role and title having long ago been replaced by money. Does this help you to understand why we now have masses of people who place a higher value on money and the unnatural social construct called “jobs” (which long ago replaced meaningful, useful, natural work) than on the climate and the biosphere itself?

There may have been a time (or particular times and circumstances) when money was a relatively harmless or neutral inanimate object, void of any intrinsic character (good or evil), but now—in this time like no other before it—things have changed. The problem with money—in our current dire dilemma, as the Earth and all who dwell therein are facing the likelihood of the worst catastrophe in human history—is the power that money has been given to perpetuate the engines of the monstrous machine that has actually created the imminent catastrophe.[4] The economic system that most humans in the world today live under is dependent upon the continued production and consumption of things that are actually toxic to our personal and environmental health. The personal human health issues brought to us by junk foods, junk pharmaceuticals, and toxic petro-chemical agriculture are better-known, more widely-acknowledged and easier to talk about than the over-riding, all-inclusive health issue created by the continued and still increasing emissions of CO2 through the use of fossil fuels. But the climate issue–the destruction of Earth’s atmosphere and biosphere–should be our primary concern, for, without a drastic change to our industrial, economic and consumptive activities, it will ultimately bring extinction to the healthy and unhealthy, alike. That monstrous machine, the money-fed, toxic industrial production and consumption system, has brought and continues to bring us phenomena like: the disappearance of glaciers, arctic ice and permafrost; the accelerating releases of methane; the increased frequency of droughts, floods and other extreme, abnormal, unpredictable weather patterns; the daily mass extinctions of species of animals, plants and microorganisms; rising seas engulfing small islands and bearing down upon the majority of human cities, which are located upon the world’s coasts; new migrations of humans and other species as “climate refugees,” newly released viruses and epidemics, and many other evidences of climate disaster that continue to accelerate beyond the rates that scientists predicted just a few years ago. The prevailing system is also dependent upon keeping us enslaved to itself through financial debt and media brainwashing, which includes convincing people that there is no possible better system, and that the best we can hope for is to mildly tweak the system we have, working through the “proper channels.” But those channels are corrupt governments that are also enslaved by the multinational industrial corporate elites. This system is designed, structured, and intentionally maintained to perpetuate itself and continually bring the “benefits” of disproportionate material rewards and political power to a very tiny percentage of the people of this planet.[5] Under these conditions, our continued entrapment in currency-based artificial economies—whether capitalist, socialist, or other—continues to push us further away from any possibility of resolution to this crisis.

Anitra Nelson, an Associate Professor in the School of Global, Urban and Social Studies at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, provides us with a clear analysis of how capitalist as well as other monetary-based economic systems are locked in to perpetuating the current global crisis:

This insecure environment of prices, supplies and markets for their goods and services makes capitalists play a game, like all games using skill, knowledge, experience and luck. The profit imperative evolves from uncertainties around input and output prices, especially future prices. Because of all the uncertainties of this game, owner–managers are forced to set an asking price that is likely to be the maximum current price that purchasers are likely to be prepared to pay. Thus the incessant focus on trade, making of profits and expanding production for trade under capitalism, the escalation of private ownership and social reproduction of monetary values, all of which contribute to growth in monetary terms. Growth is not optional but rather implicit in the ordinary, everyday running of a market-based economy.[6]

As many observers of the relationship between economic growth, increased production of toxic products, and the increase in CO2 output have already written,[7] we cannot continue growth in the existing industrial market-based economies and simultaneously reverse the process of global warming. Nelson goes further and explains how socialist reforms, co-operative exchange, and non-profit industrial models also perpetuate economic and industrial growth (and thereby perpetuate global warming) as long as those models are enacted within the structures of market-based, monetary systems:

Even replacing capitalist enterprises with ‘not-for-profit’ cooperatives, does not extricate us from a profit-making system or growth economy. So-called ‘not-for-profit’ enterprises must aim to make profits and only distribute them in ways that depart from normal business practice with, say cooperative members distributing profits to local communities. Like those following voluntary simplicity in an over-consuming society, businesses that might try to practice degrowth, say making less money than they did the year before, would be wholly vulnerable to market forces and would risk losing control over, rather than reappropriat[ing] means of production.[8]

Money itself has become the corporate industrial monster’s ultimate weapon, as well as the shackling chains by which the “1%” has the rest of us in bondage, while most of us humans sit and watch “helplessly” as they ravage and plunder the only planet that we have. Monetary economic systems (whether you are under the semi-socialist system in China or the capitalist system of the U.S.A, or any other unsustainable mega-nation or empire) and our subjection to them give these corporations, governments and banks their leverage and their force. The very fact that they have us physically and legally in debt to, and psychologically bound to, these corrupt, unnatural, arbitrary and unnecessary monetary systems is what makes people go to work in toxic, destructive places like the tar sands of Alberta or the Bakken “oil fields,” the Monsanto laboratories, or the Fukushima nuclear plant. People don’t work in oil fields, toxic chemical plants, or coal mines because they love the stench and the filth of those places, and the negative impact on their health. The workers, managers and CEOs are all there for the money. It is money and the leverage of the monetary systems, especially debt and credit, but also the psychological fear generated by market insecurities, that stimulates ruthless competition (for profits or jobs) and makes even the best of the politicians in this world either completely subject to the will of the corporations, or impotent in their attempts to regulate or stop them. It is money that perpetuates the commercial brainwashing of these mostly submissive, unquestioning, unimaginative, stupefied human cultures and makes us believe that we’ve “gotta have it,” “can’t live without it,” and therefore must ruthlessly compete with each other and submit to the system, even when it orders us to compromise our consciences and participate in activities that we know are wrong, or even deadly. The currency systems, in which all products and us people, too (not just our labor, but also our time, our energy and our health), must be bought and sold for a monetary price based on arbitrary, unstable market values, in an extremely competitive market, often compel people to lie and deceive, or steal outright, and sometimes even kill. The powers of the money world, especially bosses and banks, have perpetuated fear and insecurity about the potential “disaster” of not having enough money, while simultaneously convincing people that there can be no other way to live than in submission to their system and their rules. But, again, more importantly than all of the above, these monetary systems also alienate us from the true source of all wealth and all life—the natural world—and deceive us into thinking that these human-crafted strange objects we call “money” are the real wealth that we must covet and pursue endlessly, and that there is no other alternative.

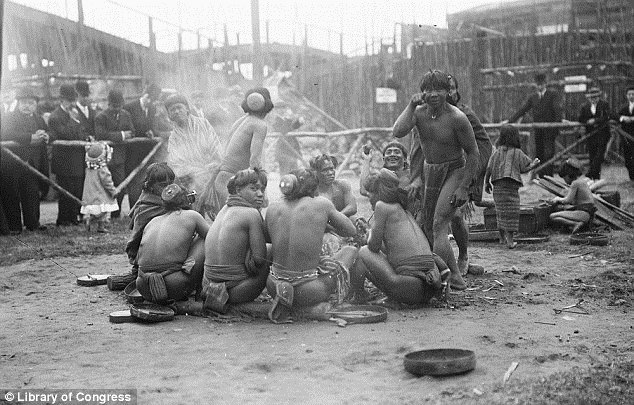

Is the continued use of money and the deadly, life-sucking bondage of our current economic systems really inescapable or perpetually locked-in? One thing that most humans do not realize, in part because the pursuit of money is so normalized and unquestioned and, in part, because relatively few people have heard it, is that we humans lived fairly well, most of the time, during the 97.5% of our existence that we lived without money. It was normal throughout most of human history (including what most Eurocentric elites call “pre-history”)[9] for people all over the world to live in small, sustainable, earth-friendly societies with abundant natural resources and a deep knowledge of, and reciprocal relationship with, the natural wealth of the Earth’s living systems. We had plenty of varieties of healthy natural food, clean water, teas, and juices to drink, and a vast store of knowledge about natural medicines. We lived in small, well-insulated, comfortable, earth-friendly houses (why call them “huts?”) when we needed shelter, and delighted in spending most of our time outdoors. We knew how to gather and make everything we needed without harming our world. Contrary to popular misinformed opinion, we were not “scraping to get by,” always in danger of starvation or attacks by wild animals, or constantly “at each other’s throats,” engaged in endless, perpetual wars (that would much better describe the present state of homo sapiens sapiens). The slanders and misrepresentations about the state of being and quality of life of first peoples, worldwide, were intentionally perpetrated by the justifiers of colonialism, genocide and empire building, including the early academic anthropologists of the 19th century. During the same era in which the atmospheric and surface temperatures of our planet began their dramatic and steady rise, due to increased industrialization, these people hoped and predicted that indigenous peoples and their Earth-friendly ways would soon become extinct. One of the clearest of the many examples of that sort of thinking and its perpetuation was presented at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 (officially called, “The Louisiana Purchase Exposition”), where they put live indigenous people from around the world on display, with descriptive commentary declaring their racist, imperialist lies.[10]

Ingorrot indigenous people of the Philippine Islands on exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition (a.k.a., the St. Louis World’s Fair), St. Louis, Missouri, 1904.

Ingorrot indigenous people of the Philippine Islands on exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition (a.k.a., the St. Louis World’s Fair), St. Louis, Missouri, 1904.

Although the view that I present here is the opposite of what most people have been taught about so-called “prehistoric,” or, actually, pre-unsustainable, human societies of indigenous peoples, many anthropologists over the last forty or fifty years have confirmed this newer view to be accurate.[11] These more recent anthropologists have reported, based on their field observations of such societies that still exist and who have a sufficient amount of their homelands still with them, that the people in those societies work less hours, have more leisure time, and are happier and healthier than most people in modern industrial technological societies. If we can relearn some of these ancient, life-nurturing and life-sustaining ways and combine them with any clean, sustainable technologies that we have created since the time that our ancestors departed from those ways, we can also re-organize ourselves into small, cooperative, Nature-directed, sustainable societies (and larger allied networks of such societies), and free ourselves from any need for, or attachment to, monetary systems. That may seem improbable to most people who have known nothing but the current prevailing social constructions, and who have been grossly misinformed about the real life ways and circumstances of small-scale, sustainable indigenous societies (both past and present). To that I will simply say that there is much for us all to learn about Earthways and our untapped human potential, and so much that we don’t yet know. We are still the same species and this is still the same planet (all changes considered), so, if we did it before, why can’t we do at least something like that again? Of course there are questions about current human population size and ecosystem carrying capacities, that we probably cannot resolve definitively without actually making the attempt to redirect ourselves toward true sustainability and begin (or continue, for those who are already on this path) the learning processes. We would also need to have many serious, democratic discussions about which familiar modern technologies and “conveniences” we would need to give up, either temporarily or permanently. What other viable (for the long term) choices do we have?

What I am talking about here is actually the ultimate form of “going on strike” and the ultimate boycott. By creating such alternative, local, non-monetary economic systems, in harmony with Earth’s systems, and getting enough of the human population, worldwide, to join into such systems, we could then effectively disarm the corporate industrial/financial death machine and stop the destruction of our planet. Our independence from the death machine mega-nations, their currencies, and their toxic products, which we will no longer need, will make their industries unprofitable (reducing sales way below their acceptable profit margins and allowable risks), and eventually crash their economies, removing all of their leverage over us, and simultaneously breaking all of the chains by which they have had us bound for so long! That would be a true declaration of independence and a very real non-violent revolution! The independence gained from our worldwide boycott of the system could lead to a restored interdependence, or, reciprocity, with all parts of the natural systems of Life, for our interconnected, mutual benefit. We can and must unite our energies, minds, and abilities and come up with alternative, Earth-based, non-monetary economic ways and technologies, and wean ourselves from the use of toxic machinery and products, in the small window of time that remains in which we are still able to save life on Earth. I would rather do this, and take the matches out of the hands of these corporate arsonists who are burning up our planet, than to continue with futile and inadequate efforts to put out the innumerable individual fires now raging against life on Earth through our acts of protest and attempts to pass regulatory laws.

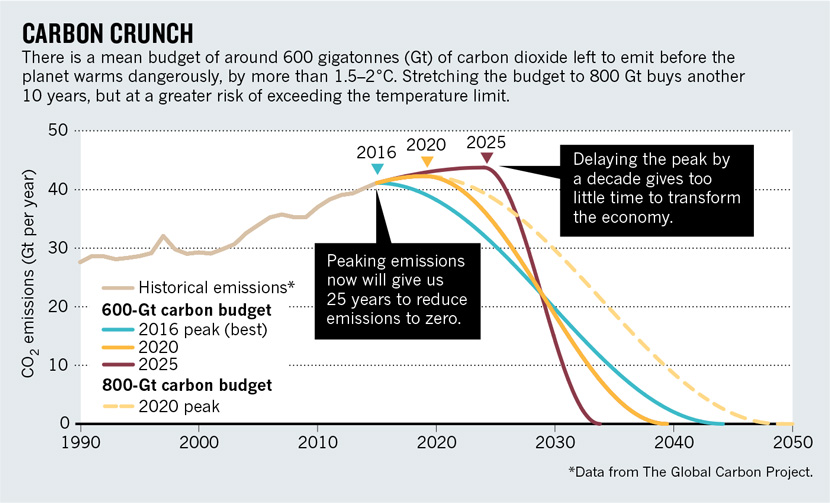

While patient pursuit of gradual, incremental change, “working through the proper channels” might have been a reasonable, pragmatic method of attaining progressive social evolution in times past, we are now in a time like no other our species has ever known, and in a crisis that demands much more immediate and drastic action. I strongly doubt that the purveyors of the global ecological and economic crises, who continue to increase the tightness of their grip on the U.S. and other national governments, through laws like “Citizens United” and treaties like the nearly-ratified TPP, will allow us to vote away their power through democratic political processes. Historically, that is just not what empires do. For the many reasons that I outline here, I am persuaded that we must, “vote with our feet,” with our actions and with how we choose to live on this Earth, and that the actions that I propose here, and many actions that are already in motion around the world, really do have the potential to make the changes that must be made. The following scientific chart helps to illustrate why immediate and drastic action is now called for. (This chart was made in 2017 and I am now writing this final edit of this essay in January, 2019.) [12]

I realize that this path will initially seem too daunting, and even impossible to most of us modern humans, and also undesirable and even appalling to many of our species who are so alienated from nature and acclimated to the unnatural, “modern way of life.” But, as more and more people tune in to alternative sources of information and become aware of worldwide phenomena like the accelerating impacts of climate change that I previously mentioned, along with accelerating wealth inequality, wars waged solely for economic profit, police brutality and a host of other societal ills that they also find troubling, they are becoming more open to the idea that radical social change may actually be necessary. I know that among the greatest fears that we humans carry are the fear of the unknown and the fear of the loss of what is familiar, what we have prepared for, and what we have already committed ourselves to—in short, the only way of life that we really know. Consequently, those among us who are the most deeply invested in the “success” of the current system, who see their own personal success as deeply intertwined with the perpetuation of the status quo, and in many cases feel that their investment in the system has actually rewarded them significantly, will have an especially difficult time hearing any of this. And then there is the majority of us, who may not feel significantly rewarded by or fond of the system at all, but have been persuaded to accept the idea that there is no way out, or no realistic alternative to the dominant, entrenched patterns of “modern life.” As awareness of the deteriorating global circumstances brings people to start looking for possible alternatives, there is something even more powerful and compelling than fear of catastrophe that might motivate them to engage in that pursuit. I call it “the appeal of the potential good,” or the anticipation of great pleasure and relief from a heavy, oppressing burden, accompanied by the possibility of a life of real joy and peace. This appeal manifests itself most and proceeds to increase when people begin to view and experience actual models of ideal, alternative, nature-based, sustainable communities. I will now devote the rest of this essay to describing some of these types of models that are already in existence, around the world.

Part 2: Models and Possibilities for New, Sustainable, Non-Monetary Economic Lifeways

Perhaps the best and most widely-visible examples of the development of sustainable, community-based economics which can empower independence from the commercial, industrial market system, can be found within the organic farming-based local food movement. This movement has much of its roots in the “back to the land” and “grow your own” movement of the late 1960s and early `70s, but the 21st century has seen a real surge in this kind of action and thought, perhaps even more serious or earnest than that earlier phase. The movement for growing and consuming our own food, rather than purchasing it with money, is not as large as the complimentary local food movement, in which people try to buy as much of their food as possible from local farmers. That is probably due to the difficulty of finding time for farming and gardening with as much time as people have to put into the work that they do for money, in this increasingly competitive and insecure job market. In 2014 there were 8,268 farmers’ markets in the U.S., which was a 180% increase from 2006. “In 2012, 163,675 farms (7.8 percent of U.S. farms) were marketing foods locally, defined as conducting either direct-to-consumer (DTC) or intermediated sales of food for human consumption, according to agricultural census data.”[14] “Intermediated sales” refers to practices like local grocery stores and restaurants purchasing and selling food raised by local farmers. The United States Department of Agriculture report, from which I found the above statistics, confirms that the local food movement has caught the government’s attention, but the report only covers market concerns regarding the movement—issues of profitability and monetary trends—and demonstrates no interest in the increasing number of people growing their own food for direct consumption, rather than for money.

In my own experience, as an organic food grower since 1970 and a permaculturalist since the mid-1980s (long before I had even heard the word “permaculture”), it seems to me that the permaculturalists and the Native American “food sovereignty” activists are the food growers and wild food caretakers who are, in general, the least interested in growing food for money, and most interested in doing those activities as part of a quest for alternative, sustainable ways of life. [15] The recently-formed, and still forming on several American Indian reservations in the U. S., food sovereignty movement is a Native American movement to take back control of our food sources and our own health through cultivating our own culturally traditional foods, as well as becoming more familiar with the traditional wild foods and medicines of our own lands and cultures. In that sense, food sovereignty has great potential for becoming a part of, or even possibly a leading example of, the international declaration of independence from the corrupt systems that I mentioned earlier. However, because most reservation communities are still battling many severe economic as well as health-related issues which resulted from European and U.S. colonialist impositions on their lives and local worlds, the focus there has been on more immediate solutions that still involve increased cash flow and working with the current, prevailing economic system. Getting away from the monetary system, then, is not yet even on the radar for most Indian reservation communities, although some conversations along those lines have started, here and there, with the help of the food sovereignty movement and the Earth/Water protector activists. Most non-Native permaculturists whom I know or have heard of have not moved that far away from still using money, either.[16]

If one is familiar with indigenous perspectives and practices of horticulture (growing food for direct consumption rather than for a commercial or monetary market), it is not difficult to see the indigenous roots of permaculture. Indigenous cultivation of the land for crops, worldwide, throughout history, has always followed the principle of working with their specific ecosystems rather than trying to alter them, which is also a guiding principle of what is now called permaculture.[17] Although we vary somewhat in our individual approaches to it, by definition permaculturists are committed to allowing our local ecosystems to guide and shape our interactions with the land and water, instead of us shaping those spaces only as we see fit. We are engaged in caretaking and preserving the native food and medicine plants and trees on the lands we live on, and planting and cultivating only those crops that are compatible with our ecosystems: the land and water and everything that lives there. We treasure bio-diversity and have deep respect for everything that belongs to the land and water that we live with. All of the living things that belong here[18] have an equal right to be here and multiple purposes for being here. They fit together and reciprocate each other and have been doing so since long before we humans arrived. It is our goal to fit in with those life-giving natural systems, to be a reciprocating part of it all—not to force the ecosystem to fit into the unnatural world of modern humans and their artificial, monetary ways of being. We would not enter into a land-water system and say, “this looks like a good place to grow ___________, and we should do so because that crop can bring us much money.” When first coming to live on a place of land and water, we would seek to learn what that place asks of us—what good could we do for that place so that it can continue to freely share its gifts of life with us and the other species who are a part of this place? How do we become a useful, helpful part of it all? How can we right-fully belong to this place? Knowing these natural systems are greater, healthier and more real-life-giving than any human-created economic system, we humbly and prayerfully plant our compatible crops right along-side and interspersed with the native crops, wherever there might be enough room and water. Although we sometimes move water around to service the crops (irrigation), we realize that it is best to plant seeds or transplant plants into the naturally wetter places where nature will bring water to the plants, if possible. There are many other ways in which the harmonious methods of permaculture take shape and merge with the various ecosystems, worldwide. These methods are both ancient and new, rooted in the ways of First Peoples going back to the ages before the advent of unsustainable megasocieties.

So, if most people in the local food movement—with the exceptions of some subsistence permaculturalists, some indigenous food sovereignty activists, home gardeners and some non-monetary trading done in community garden spaces—are still selling their crops for money, where do we find examples of people who are doing other things for the purpose of freeing ourselves from the monetary systems? One would think that some good models for moneyless local economies could be found in the barter fair movement. Bartering has always been a part of human interaction, but began to spread more widely as an active form of resistance to the industrial capitalist system in the early 1970s, with large outdoor gatherings often called names like “The Barter Faire” (that spelling of “Fair” reflects a previous movement called the “Renaissance Faires”). Barter fairs were kind of like “counter culture” swap meets, with an intention of economic sharing and exchange, avoiding the use of money. Over the years, the commitment toward not using money at the barter fairs waned and so did the barter fair movement. One of the first and biggest of the counter culture barter fairs, the “Barter Faire,” of Okanogan, Washington, founded in 1974, eventually dropped the word “barter” from its name and is now called the “Okanogan Family Faire.” Whereas originally everything was (mostly) moneyless and free, now “vendors” pay for spots and customers pay for admission tickets, just so they can go in and shop, making it even more money-oriented than most swap meets or art festivals. Some bartering does occur at the few remaining barter fairs, but mostly between the vendors. The old barter fair movement may have faded away, but the good news is that bartering is by no means dead. It is actually thriving and growing and the primary locale for this new bartering movement is the internet. There is also a new, 21st century upgrade of the old outdoor barter fair movement (without the bartering or any direct exchange), an international phenomenon called, the “Really, Really Free Market,” which holds much more promise as a movement for actual systemic economic change than the old hippie barter fairs did.

Before I return to describe the RRFMs in more depth, I will first comment more on the phenomenon of online moneyless trading. In a short essay by Christopher Doll, a research fellow at the United Nations Institute of Advanced Studies, titled, “Can We Evolve Beyond Money?,” Doll describes how the internet has created the infrastructure for greater, more widespread possibilities for economic sharing and moneyless “collaborative consumption”:

…the internet has reduced the friction costs of searching for what is available and massively enabled peer-to-peer transactions to be done on a far wider scale than has ever been seen before…If, as it is frequently argued, Generation Y is the first generation of digital natives and sharing is their norm, could it be that collaborative consumption rather than consumer capitalism will be their norm? If so, what will the next generation bring?[19]

This is very exciting. I remember when the internet was first coming into popular usage, back in the early 1990s, and a conservative radio commentator was freaking out over his perception that too much was being given away for free on the internet and he did not see enough people using it to make money. Hearing that comment, coming from a truly repugnant individual who embraces nearly everything about our societal system that I loathe, actually gave me the nudge I needed then to step away from my slightly Luddite skepticism of that new electronic communication medium and give it a chance. Ever since then, the internet has been one of my most indispensable tools for communication. The free flow of ideas and information, so many people creating their own “broadcast channels” and being able to do so and interact with multitudes of others for free (except for equipment and access charges), usually without any government censorship, has created opportunities for revolutionary change way beyond any media that we had prior to the internet. (Even so, there are other environmental and health-related costs to using the internet and the electronic devices for accessing it that we will eventually need to weigh out when we debate what technology to keep and what to leave behind.) Two generations of humans who are now used to all of this “free”[20] access—to ideas, to goods, and to services—has made it more possible than ever to enable and equip people for substantial, systemic transformations of all kinds, including world-wide, non-violent economic revolution. There is a compilation of bartering and swapping websites in an article by David Quilty, titled, “36 Bartering and Swapping Websites—Best Places to trade Stuff Online,” posted on a financial advice website called, “Money Crashers.”[21] There are many more than just these 36 sites, which is revealed in the comments after the article, as person after person writes about sites that the author missed. Some of these sites allow for some use of money, but most are focused on barter and sharing. Some of the sites have a socio-political agenda for avoiding the use of money (like “Freecycle” and the “Freegans,” whom I will describe below), while many others seem to be just trying to save money or mitigate circumstances related to poverty. As the social change advocates interact more with the simply economically-straddled people on these websites, seeds of revolutionary thinking are most certainly being sown. Every time a person experiences economic benefit without the use of money, a new sense of what might be possible is further developed and strengthened.

From my perspective, the two most interesting websites on the list, which do the most toward addressing the pertinent systemic issues and working toward creating the possibility for an international boycott of the system, are Freecycle and the Freegans.[22] Freecycle (http://www.freecycle.org) describes their organization as, “..a grassroots and entirely nonprofit movement of people who are giving (and getting) stuff for free in their own towns. It’s all about reuse and keeping good stuff out of landfills.” Founded in Tuscon, Arizona in 2003, by a recycler named Deron Beal, Freecycle is now a very large network (5,289 groups in 32 countries, and 9,105,322 members) of local, volunteer-run sites.[23] Connections are made for giving and receiving online. There are two categories of posts, “Wanted” or “Offer.” Users have to be registered members to reply to posts and make their own arrangements for contacting each other. Membership is free “and everything posted must be free, legal and appropriate for all ages.”

The Freegans organization is a little more direct and explicit about their revolutionary motivation for abandoning the prevailing economic system. This is how they describe themselves on their web page:

Freegans are people who employ alternative strategies for living based on limited participation in the conventional economy and minimal consumption of resources.

Freegans embrace community, generosity, social concern, freedom, cooperation, and sharing in opposition to a society based on materialism, moral apathy, competition, conformity, and greed. After years of trying to boycott products from unethical corporations responsible for human rights violations, environmental destruction, and animal abuse, many of us found that no matter what we bought we ended up supporting something deplorable. We came to realize that the problem isn’t just a few bad corporations but the entire system itself.

Freeganism is a total boycott of an economic system where the profit motive has eclipsed ethical considerations and where massively complex systems of productions ensure that all the products we buy will have detrimental impacts, most of which we may never even consider. Thus, instead of avoiding the purchase of products from one bad company only to support another, we avoid buying anything to the greatest degree we are able.[24]

It looks like the Freegans and I think a lot alike, but I had never heard of them until a few days before I began writing this section of this essay. Apparently, one of the strategies that they are well known for is “dumpster diving” (a.k.a., “urban foraging”), a practice that I also used to engage in, back when I belonged to a certain communal society (which I will not name) in the early 1970s, when I was about the same age as many of the Freegans that I saw pictured on their webpage. But rest assured, the Freegans are engaged in much more than just dumpster diving. Their wide range of activities include: widely and freely distributing and recycling the wide variety of good quality thrown away products that they find in waste bins; creating free organic soil for gardeners by composting the spoiled food and other organic matter that they find; creating and freely distributing biofuel from disposed restaurant cooking oil and other vegetable oil; repairing and redistributing broken mechanical items and equipment; they “occupy and rehabilitate abandoned, decrepit buildings” to provide homes for the homeless and to create community center gathering places; create organic urban free food gardens on vacant lots; foraging for wild plant foods and medicines; sharing surplus vegetables, fruits and nuts produced by local farmers, and several other related activities. Freegans work with other recyclers and re-users, and with other, like-minded organizations, such as Food, Not Bombs, homeless shelters, and the Really, Really Free Markets. The Freegan website gives much information and links about what they believe and what they do, but not any personal information or history of how their movement began. Also, to be clear, even though the Freegans have a great website, by which they connect many sustainability activists, young and old, most of what they do is done offline, in the streets and various public spaces. Freeganism has spread internationally and there are now Freegan groups in the U.S., France, Brazil, Norway, Greece and Lebanon.

The Really, Really Free Markets are not actually barter markets, because no direct exchanges are allowed there. No money, no deals, no selling, no trading, just “Take what you need, and bring what you don’t.” A chalkboard sign put up at one of the RRFMs says, “Do not compete for an item. This is a no-money market. No trade, swap, barter, or sale.” Participants can offer their skills and services, as well as material goods, and the events are held in public parks and other public spaces. The RRFMs are examples of what is known as a “gift economy,”[25] in which every material need is met for free, based on a perspective that there is truly “enough for everybody,” if we properly take care of and manage our abundant resources. Of course, such a perspective can only be successfully applied if we eliminate resource insecurity and greed, which raises the question of what happens when a greedy, insecure, or capitalistically well-conditioned person goes to a Really, Really Free Market? (I’ll leave that question unanswered for now, partly because I suspect that it has a wide variety of possibly valid answers.) The compatibility between Freegans and the RRFMs is glaringly obvious and it is easy to see why they collaborate so well and why so many Freegans are involved with organizing and running RRFMs. These intertwined movements both seek to stop the destructive and wasteful effects of the capitalist system and introduce people to different forms of economic practice, as well as of human interaction. The first RRFM occurred in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2003, and the idea sprang forth from a meeting of the free food/anti-hunger organization, Food, Not Bombs. That same year, two more RRFMs were held, one in Jakarta, Indonesia, the other in Miami, Florida. Since then, RRFMs have been held in dozens of U.S. cities, and Canada, Australia, Malaysia, Taiwan, England, South Africa, and Russia. The movement is very popular in Russia and has spread through many cities there.

Although there are many more examples of non-monetary economic practices and organizations that are working towards that end, I will just mention one more here: time banking. The time bank idea was conceived and developed in the early 1980s by Edgar Cahn, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia School of Law. Cahn calls time banking, “an alternative currency system in which hours of service take the place of money,” and provides this further explanation:

[time banking is] a mode of exchange that lets people swap time and skill instead of money. The concept is simple: in joining a time bank, people agree to take part in a system that involves earning and spending “time credits.” When they spend an hour on an activity that helps others, they receive one time credit. When they need help from others, they can use the time credits that they have accumulated.[26]

In the twenty-four years since Edgar Cahn founded TimeBanks USA, time banking has spread to more than 30 countries—including “China, Russia, and various countries in Africa, Europe, North America, and South America.” In the United States, there are “about 500 registered time banks, and together they have enrolled more than 37,000 members. The smallest of them has 15 members; the largest has about 3,200.” Time banking is easily facilitated by a computer database that enables members to register the skills or services that they can offer and find people who can provide them skills or services that they might need. Hours of time credit and time debt are also kept on the database and each local community time bank has their own database. “Worldwide, time bank databases document more than 4 million hours of service. (And that figure understates the true scope of time bank participation: Survey data indicate that at least 50 percent of time bank members do not record their hours of service regularly),” Cahn writes. That last remark, in parentheses, contains evidence of a very powerful phenomenon that occurs frequently in these moneyless, community-connecting, local economic activities: the intrinsic rewards, like having your own skills valued by others, making connections and friendships through giving and receiving, and developing social trust or “social capital,” become more valued than the extrinsic rewards from receiving services or material gain. Examples of that profound experience are expressed over and over by people involved in freeganism, the RRFMs, time banks, Food, Not Bombs, Freecycles, and many other community-based, alternative economic efforts. Christopher Doll describes “social capital” very well:

What is intriguing about collaborative consumption is that the credit rating upon which so much of our access to goods and services currently depends will be replaced by a new rating—our own personal trustworthiness rating. That is to say, our access to goods becomes, in part, a function of our social capital rather than our financial one. This is an incredibly powerful concept in helping us understand personal wealth in broader terms and indeed, what we might use in place of money. Social capital accumulates over time: the more you share properly, the higher your rating rises, which in turn promotes good social conduct. This is all good in theory, provided that personal freedoms and identities aren’t compromised in the process.[27]

It is in this process of cultivating “social capital,” or what could also be called “relationships of trust,” or, “trustworthy reputations,” that we find the personal accountability within moneyless systems. People naturally want to be trusted and accepted and they want to interact with other people whom they can trust and rely upon as dependable and caring persons. When requests for money (whether it be a market price or for a charitable cause) are involved in our interpersonal and public interactions, there is always some degree of suspicion as to the motivations, legitimacy, or actual need of the person or organization making the request. That particular burden would eventually become very rare, or perhaps even disappear, in a moneyless, reciprocal exchange, or gift economy, as people get to know each other in their local communities better. What also becomes clear when observing and considering how these moneyless systems actually succeed, is that they function best at the local, small community level, rather than in the context of the anonymity of a sprawling, unsustainable mega-society. To create systems like these in large towns or cities, would likely necessitate the division of the populations into manageable neighborhood-sized economic cells, if urban life will be feasible at all after the collapse of the current mega-societies. Hopefully, what the development of local, moneyless, natural life-connected economic systems will do for us and our planet is restore much of what we all had 5,000 years ago, before the advent of mega-societies, empires and money.

Even though I live on a farm 37 miles north of the town of Missoula, Montana, I belong to the Missoula Time Bank. I recently interviewed two of my friends, Susie Clarion and Carol Marsh, who were part of the small core group who founded the Missoula Time Bank, back in the Spring of 2013. There are now 141 members in the MTB and 2,647 hours exchanged, as recorded in the database, but Carol told me that she and others she knows sometime fulfill requests for services and then do not record the hours, which again reflects the perspective that the experience of the transaction, or interaction, is often reward enough in itself. In the Missoula Time Bank we also have what is called a “Community Chest,” through which we can donate some of our hours for community service group projects, like building houses with Habitat for Humanity. My friends also pointed out another lesson they have learned through their time bank experiences: it is just as valuable to ask for and receive services as it is to give. We spread that good feeling of having our gifts and skills valued by others through being available to receive from others. Mutual benefit and reciprocity are major values in the time bank system, as expressed in this quote from the website, “The question, `How can I help you?’ changes to `How can we help each other build the world we both want to live in?’ Time banking is based on equal exchanges. Everyone benefits because every member both gives and receives.”[28] As Susie Clarion said to me, “Providing services through the time bank is not just doing a job. It is the interaction and bonding, the listening and teaching, which are the true values of the time bank experience. What people seem to enjoy most about their time bank experiences is making good friends.”[29] There are also occasional social events for time bank members and anybody who might be interested. Edgar Cahn provides us with this clear summary of what time banks can do:

“Each transaction flows from a relationship, and such relationships create a spirit of trust that allows people to reweave the fabric of community. A currency that treats all hours as equal does more than simply provide an alternative to market price as a measure of value. It empowers people whom the market does not value and validates their contribution to society.”[30]

When I peruse these sorts of examples of alternative, non-monetary, community-based economics, which are already in place and spreading, I become more confident that an international boycott or abandonment of the current prevailing economic system is possible. We are already laying the foundations and creating the infrastructure of what can replace it, and the momentum is building up. That may be cause for inspiration or even celebration, but I caution all who might be willing to go forward with this movement, there is good reason to publicly temper our exuberance and to welcome public skepticism. If this revolutionary strategy sounds unlikely or impossible to most modern humans, consider this: it would have to be laughable to work. It really must be laughable. Any non-violent[31] revolutionary strategy which intends to bring to a halt the destructive forces of our current political and economic systems and replace those systems with their opposite—a life-supporting, sustainable, Earth biosphere-led, humane, just, interconnected and mutually, equally beneficial to all living beings, new international network of local, ecologically-specific economic systems—has got to be laughable, scoffed at and easily dismissed by the oligarchs and the tools who serve them, if we don’t want our movement to be brutally squashed and destroyed. If they hear about what we are doing, we want them to laugh, mock us, call us “crazies,” question our intelligence, dismiss us as fools, and then ignore and forget about us. “They think that they can grow all of their own food and medicines, make their own clothes, build their own houses and other structures, transport themselves sufficiently without fossil fuels, create their own electricity, and boycott all of our industrial products! That’s insane! And get people all over the world to do that? That’s even crazier!” Yes, that’s what we want them to think and say to themselves and each other. Right. Nothing to see here, Comfortable Ruling Class. Just go on with your obliviousness and your delusions. Entertain yourselves and spend your money while it is still worth something. Then, one day, you will come to us waving your silly, worthless currencies in your hands, asking us to feed you and clothe you, or give you shelter, and we will say, “That is not how we do things here, in this new world. We belong to Life and to each other. We take care of this living world that gives us life together. We work together, play together and share everything. Freely we have received and freely we give. If you are ready to learn and experience what it means to truly live, come and join us.”

We won’t know what is possible until we give this revolutionary transformation our greatest, unified (or at least mutually supportive) effort. There might be many more people, worldwide, who are ready for this (including those who do not yet realize that they are ready for this!) than we have been led to believe.[32]

[1] I date the use of currencies as beginning shortly after the first unsustainable mega-society arose. The earliest one on record is that of the Mesopotamians about 5,000 years ago, but they are not necessarily the first. There were probably some slightly smaller, less ecologically-disruptive megasocieites before them who did not leave as much archeological evidence of their existence and have yet to be found. The first Egyptian empire may have spewed forth about the same time period as Mesopotamia.

[2] This practice was applied by the more mobile or “nomadic” tribes as well as the more sedentary, village-oriented tribes. It is also one reason why many tribal nations, worldwide, have several related branches or subdivisions of their tribe. The ancient focus of pre-currency tribal societies on harmonious relations with their ecosystem, including other tribes, as well as other species, obviously contradicts the prevailing belief of western colonialist minds that tribes were always either at war with each other, or in a state of tension and hyper-vigilance in between wars. The word “tribal” has even become synonymous with “war-like,” which is a gross misconception created to justify and normalize centuries of brutal western colonialism and empire-building. The stereotype is actually much more apropos in application to western capitalist, colonialist empires. Traditional tribal societies, before the disruptions of colonialism (but even since then for many), have always bonded and maintained peace with neighboring tribes through inter-marriage, gift-giving, and in some cases, even shared ceremonial activities.

[3] Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future, N.Y., Harper-Collins, 2011. David C. Korten, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2007.

[4] For a detailed description of the present crisis, with source links, see, George R. Price, Thinking About the Unthinkable, in Learning Earthways, https://georgepriceblog.wordpress.com/2013/12/28/thinking-about-the-unthinkable/ . More recent updated information can be found in Bill McKibben, “Recalculating the Climate Math,” The New Republic, September 22, 2016. Here is one of the best sources online for scientific articles and discussion on climate change, by climate scientists: http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2007/05/start-here/comment-page-6/#comments

[5] How small that percentage might be is a subject for much more research and examination on a worldwide perspective than is usually done. The familiar claim that these benefits go primarily to “the 1%” may turn out to be a high figure if we were to examine and measure it from a global perspective. If we measure benefits and costs beyond just monetary statistics and across all species, not just for humans, the figure for who receives significant net benefit from our economic system might be infinitesimally small.

[6] Anitra Nelson, Non-Monetary Degrowth is Strategically Significant, Paper delivered to the 5th International Degrowth Conference in Budapest (Corvinus University), 30 August–3 September, 2016, pg. 5.

[7] See, for example, Herman Daly, Beyond Growth: the Economics of Sustainable Development, Boston, Beacon Press, 1997; Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2015; Giorgos Kallis, “The Degrowth Alternative,” Great Transition Initiative, February 2015; and Jason Hickel, “Why Growth Can’t Be Green,” Local Futures, September 18, 2018, https://www.localfutures.org/why-growth-cant-be-green/

[8] Nelson, 2016, pg. 6.

[9] Although many other historians designate the pre-literate or pre-written records period of the 200,000 year existence of homo sapiens sapiens as “prehistoric,” I do not. There are oral traditions, archeological findings, anthropological analyses, and other sources that assist in piecing together a pre-literate historical record.

[10] For more on the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition of 1904, in St. Louis, Missouri, see, Eric Breitbart, A World on Display: Photographs from the St. Louis World’s Fair, 1904, Albuquerque, N.M., University of New Mexico Press, 1996. Vine Deloria, Jr., Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact, New York, Scribner, 1995.

[11] Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics, Chicago, Aldine/Atherton, Inc., 1972. Richard B. Lee, The !Kung San: Men, Women and Work in a Foraging Society, Boston, Cambridge University Press, 1979. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, The Old Way, A Story of the First People, New York, Farrar Straus Giroux, 2006.

[12] We blockaded the “megaloads” of tar sands equipment trucks four times during the winter of 2014 and then the megaloads stopped. But what did they do instead? The oil companies spent approximately 2 billion dollars (pocket change to them) retrofitting their haulers to go on the freeways, thus avoiding any future blockade protests, and they simultaneously built manufacturing plants in Alberta to reassemble the larger equipment up there, continuing the devastation of the dirtiest, deadliest industrial project on Earth. In the late Spring of 2015, the beautiful kayak and canoe protesters in the Puget Sound slowed down the Shell Oil drilling platform ship for a little while, but it too, ultimately, proceeded on to its infernal business. A few months later, Shell decided not to drill for oil in that section of the Arctic, for the time being, for pragmatic reasons related to the profitability of the project, not necessarily because of any concerns related to the protests.

[13] Christiana Figueres, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Gail Whiteman, Johan Rockström, Anthony Hobley and Stefan Rahmstorf, “Three years to safeguard our climate,” Nature, 28 June, 2017. The 600-800 Gt carbon budget is way too high and too risky, because a 2 degree C global temperature increase is too big of a risk. We need to keep it at or below 1.5 degrees, and for that the budget needs to be closer to 200 Gt.

[14] Low, Sarah A., Aaron Adalja, Elizabeth Beaulieu, Nigel Key, Steve Martinez, Alex Melton, Agnes Perez, Katherine Ralston, Hayden Stewart, Shellye Suttles, Stephen Vogel, and Becca B.R. Jablonski. Trends in U.S. Local and Regional Food Systems, AP-068, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, January 2015, pp. 7 and 5.

[15] A good overview of the permaculture movement and many details about the practice can be found on the blog, Permies.com (https://permies.com/). The information exchange in the well-used discussion forums on the blog is extremely useful.

[16] The “sovereignty” element of the name, “food sovereignty,” is a reference to the fact that American Indian tribal nations were sovereign nations long before the arrival of Europeans in the western hemisphere, probably thousands of years for some tribal nations and hundreds of years for others. Tribal sovereignty is upheld and confirmed by the U.S. Constitution, several Supreme Court rulings, and the fact that the United States has made treaties with hundreds of individual tribal nations, something which is only done between sovereign nations. That historical context and the continued existence of treaty-established, tribally-controlled reservation lands, allows tribal nations to be uniquely situated for developing food sovereignty programs into something that can actually begin a process of creating independence from the corrupt systems of colonial capitalist toxic industries.

[17] In the recent documentary film, “Abundant Land: Soil, Seeds and Sovereignty,” directed by Natasha Florentino, one of the co-founders of the modern permaculture movement, David Holmgren, is quoted as saying that he and the other founder were inspired largely by the indigenous Hawaiian cultivation and harvesting methods that are shown in that film.

[18] This concept of “belonging to this place” is debatable and sometimes contentious. The reasons for that include the fact that we modern humans, for the most part, do not know the places where we live intimately enough to really understand why anything belongs to a specific place. The topic of “invasive species,” for example, usually involves arguments over how to get rid of species that traveled to a place (intentionally or accidentally) by the transport of humans, the general assumption being that the introduction of new, non-native species to a place can only be unnatural or wrong. Rarely, in these kinds of discussions is it taken into consideration the many ways in which Nature herself introduces new species to old places. This happens mostly through seeds being temporarily attached to those grandest of travelers, the bird species, but also through the strength of great winds like hurricanes and tornadoes. Or, how about the various species who, through their very natural activities, create habitats that welcome new plants or new insects and other species, like our friends, the beavers, the termites, and the gophers?

[19] Christopher Doll, Can We Evolve Beyond Money?, 2011, DEVELOPMENT & SOCIETY: Energy, Economics, Business, Finance, United Nations University, “Our World,” https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/our-world-3-0-can-we-evolve-beyond-money “Can We Evolve Beyond Money?” by Christopher Doll is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

[20] “Free,” as in unregulated or uncensored, but not without cost—the cost of purchasing access and equipment, as well as the environmental cost of this technology.

[21] David Quilty, “36 Bartering and Swapping Websites—Best Places to Trade Stuff Online,” posted on Money Crashers website, http://www.moneycrashers.com

[22] I say this while admitting that I still have more to examine more thoroughly, including the many websites mentioned in the comments after the article. Freecycle.org, http://www.freecycle.org The Freegans, http://freegan.info/

[23] On the Freecycle website it says, “the Freecycle concept has since spread to more than 110 countries,” but their trademark is registered in 32 countries.

[25] Genevieve Vaughan, Shifting the Paradigm to a Maternal Gift Economy, Women’s Worlds, Ottawa, July 7, 2011. Kaarina Kailo, Sustainable Cultures of Life and Gift Circulation—a New Model for the Green/Postcolonial Restructuring of Europe?, Sustainable Cultures – Cultures of Sustainability, BACKGROUND PAPER 9.

[26] Edgar S. Cahn and Christine Gray, “The Time Bank Solution,” in, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer 2015, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California.

[27] Doll, 2011

[28] Missoula Time Bank website, http://www.missoulatimebank.org/

[29] Interview with Susie Clarion and Carol Marsh, July 30, 2016, Missoula Montana.

[30] Cahn, 2015.

[31] I rule out a violent revolution because it is just impractical, or maybe impossible, against the most heavily-armed empires, with the most sophisticated weaponry, that the world has ever seen. These are no longer the days of the Bolsheviks versus the Czar, or the Cuban revolutionaries versus the Battista oligarchs, when both sides had relatively similar weaponry. Besides the brutally violent weapons technology of recent decades, just the level of surveillance and the automated, robotic military technology, which takes the decision-making processes of military action more and more out of the hands of humans with consciences who might hesitate or fail to act, makes the odds against violent revolution succeeding infinitesimally small. The United States and its allies are not continually engaged in endless war because they are not militarily capable of defeating some alleged “enemies.” Endless war is “good for business,” generating massive profits for the arms industry and its subsidiaries and financiers.

[32] If we fail to bring down the system soon enough to avoid ecological catastrophe and near-extinction, our building of alternative systemic infrastructures might provide some of us with means for being among the few survivors. We just don’t know.

For those readers who imagine salvation coming through the big “green” technologies of solar and wind, and therefore find my proposal too drastic or unnecessary, I urge you to read Ozzie Zehner’s book, Green Illusions: the dirty secrets of clean energy and the future of environmentalism, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 2012. You might also want to take a look at a website called, “Wrong Kind of Green,” http://www.wrongkindofgreen.org/about-us/ Neither one of those sources are perfect, of course, but the high quality of the research that they have done and the critical information that they have provided us should raise some very important questions about what activities and technologies are actually green enough to prevent us from continuing on the path to the 6th extinction.

For those who may wonder why I did not mention Jacque Fresco’s “Venus Project” in an article about moneyless economies, especially since that is usually the first thing that comes up when you Google search “moneyless economies” and the first example many people think of regarding that topic, I’ll just say this. I think that the Venus Project is too focused on human technology as a solution and it is not really centered on Earth sustainability. I also could have given some mention of the Transition movement and some of the intentional eco-communities in existence around the world. As far as I know, some of the Transition towns and communities have developed their own alternative currencies, but none that I know of have gone totally moneyless or even have that as a community goal. Even so, they have successfully created some community infrastructures that could lead to local, moneyless economies. https://transitionnetwork.org/ I also don’t know of any intentional communities that are moneyless, but I plan to continue with research on that topic. I mentioned the need for degrowth early in the first part of this essay, but did not discuss the growing eco-socialist degrowth movement in the second part. That was because I only recently found out that there are many people in that movement (such as Anitra Nelson, whom I cited earlier) who also have come to the conclusion that we must demonetize. When I have done more reading of, research on and interaction with these non-monetary degrowth allies, I will probably write more about that. For now, I will just say that what little I have read of their work, so far, suggests to me that the eco-socialists are a little more socialist than “eco” (or “environmentalist”) and also have a more Euro-centric analysis of the movement, with little regard for the indigenous models that preceded Marx by many thousands of years. My own approach is more ecologically and indigenous culture-based, but I see no reason why we cannot all work together towards our common goals.

One problem that those of us who are attempting to create moneyless farming communities have to face is that we at least have to generate enough currency to pay our property taxes, since no county assessor’s office that I know of will accept payment in fruit or vegetables. For most of us, there is also the issue of mortgage debt and other types of debt, or currency commitments. May all of those legal commitments to the use of currency soon be gone, one way or another.

The photo above comes from a really funny story about a guy whose dog ate five $100 dollar bills and the guy retrieved them from his dog’s poop, washed them and pieced them back together as best as he could. Because we can’t live without it, right? Photo credit and the rest of that story from Animal Radio News website, http://animalradio.com/Animal_Radio_Network_Newsroom.php

Here is a direct link to the original source of the article on the money-eating dog. It is easier than scrolling down the above link to find it amongst all the other funny pet stories:

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/man-lost-500-hungry-dog-reunited-money-article-1.1474100

Thank you for reading this, and I welcome constructive comments, ideas, and discussion in the comments section below. A much shorter version of this article was published as a chapter in an anthology on radical environmental alternative practices and possible solutions to the global climate crisis. The book is titled, Perma/Culture: Imagining Alternatives in an Age of Crisis, Edited by Molly Wallace and David Carruthers, New York, Routledge Press, 2018.